Chloe Magee and Southeastern Louisiana's Recipe for Making It Big Time

Growing up in Watson, Louisiana, Chloe Magee knew what big time looked like. It greeted her every weekend when she and her family sat down to watch LSU football games—Baton Rouge and Tiger Stadium not even 30 miles down the road.

Death Valley was big time—bright lights, massive fan base, history and deep pockets.

Big time meant the best of the best, like the stories her dad, a former minor leaguer in the Atlanta Braves system, used to tell about being around Chipper Jones in spring training. She wanted all of it. She wanted to compete against the best on the biggest stage. As she grew into a special talent on the softball field and drew interest from programs in the biggest conferences, she understood why a favorite uncle always encouraged her to “go big.”

Like the old real estate maxim about buying into the best neighborhood, even if it’s the worst house on the block, she felt the pull. But somewhere along the line, she began to wonder if life might be a bit more complex than bigger is better. Watson didn’t meet many definitions of big time, after all, but it had her people. Surely, there can be more to a place than meets the eye.

“I want to go big, of course, because I want to play at the best level,” Magee would counter to her uncle. “But I don’t want to just go big to say I went big.”

Maybe it’s why one of Southeastern Louisiana softball coach Rick Fremin’s plainspoken aphorisms—and he is not at a loss for them—rang particularly true as she weighed her college choices. Big time, the coach says, is wherever you’re at. Even Hammond, Louisiana, and the Southland Conference, where Magee ended up after turning her back on power conference interest.

“Once I had that approach, I was like, ‘Wherever I’m at, I’m going to make it big time.’” Magee said. “No matter what program was interested to me, I just imagined myself at that program. Can I make that big time for me? Can I be my best at that place? And that’s ultimately what it came down to because this program really fit my personality style.”

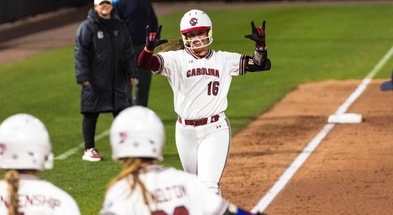

As a freshman, she was the first player in program history to earn first-team All-Southland honors. As a sophomore, she entered March hitting close to .400 with 14 stolen bases. And as much as anyone, she embodies the rather audacious experiment underway in Hammond, where Fremin’s teams have won at least 40 games in each of the past three seasons.

At a time of increasing consolidation, with five power conferences squeezed down to four and the rest of the country in danger of being squeezed out of the frame altogether, Southeastern is trying to prove big time is still where you’re at. And in a sport increasingly ruled by power and analytics, a team that keeps running in the same way a great white shark keeps swimming—for survival—is intent on using small ball to bring the big schools to their knees.

“Even though we’ve done what we’ve done, each year I’m trying to do what’s never been done before,” Fremin said. “I say that humbly, but I’m just trying to be relentless, put a unique team on the field that’s fun to watch and respects their opponent and the umpires.

“But man, I’m not there to compete. People say, ‘Your teams compete.’ I’m not there to compete. I’m there to dominate our opponent. And I don’t mean that the wrong way.”

Starting Small

A year ago, Southeastern attempted one of the most stunning regional runs since the current four-team format debuted in 2005. Playing its first ever NCAA Tournament game, Southeastern upset Clemson and reigning USA Softball Player of the Year Valerie Cagle.

Next, the Lions pushed host Alabama to the wire, tying the winners bracket game with a double steal in the sixth inning before eventually losing in extra innings. Undaunted, they beat Clemson a second time, eliminating the ACC team and earning a place in the regional final against the Crimson Tide.

This season, Southeastern led LSU in the sixth inning on opening weekend in Baton Rouge before ultimately losing on a walk-off sacrifice fly. Two weeks later, the Lions led Florida State going into the bottom of the seventh inning in Tallahassee before ultimately losing in extra innings. A second walk-off loss against a WCWS hopeful followed that weekend, this time Texas A&M. All of that despite turning over much of the starting lineup after last season’s regional.

It’s a long way from the team that went 26-29 in Fremin’s first season in 2017, the program’s eighth losing season in nine years.

It’s also a long way, at least figuratively, from Belle Chasse, Louisiana, the small community on the outskirts of New Orleans where you find the roots of Southeastern’s success.

Fremin speaks with pride about his dad and grandad, diesel mechanics who built their own homes with their own hands in Belle Chasse. They were “grinders,” he notes, lending the word the same sort of reverence others might use for positions of more obvious power or wealth.

A Belhaven University Hall of Famer as a quarterback, he tried to be a grinder at a position more associated with glamor. No stranger to softball because his younger sister, Shaunte’, played at LSU and later coached at the high school and college levels, he brought the same outlook to coaching. Southeastern players don’t jog anywhere; they sprint.

“When they show up to the park, I want pressure from when they show up until we shake hands,” Fremin said. “The players have really taken that on. … The last few years, our teams have believed as long as the bus driver gets us to the park, we can win.”

It’s a good line, and one he uses frequently. It eloquently encapsulates a matter-of-fact audaciousness. It’s humility shorn of meekness. That’s the other part of the equation at Southeastern. Because as much as his teams are modeled on what he learned from his mom and dad about work ethic and grinding, and as much knowledge as he picked up from his sister’s time playing or working with the likes of Yvette Girouard and Glenn Moore, there is another figure whose influence is easy to see when you know to look.

Even if the late Rickey Henderson had probably never heard of Hammond.

Attending one of legendary LSU baseball coach Skip Bergman’s camps as a boy on the cusp of becoming a teenager, Fremin’s ears perked up when he heard one camper would win an award named after Henderson, the outfielder who would go on to steal more bases than anyone in MLB history. Fremin wasn’t the oldest kid at the camp. He wasn’t the best player. But damned if he was going to let anyone else win an award named after the idol with whom he shared a name. Sure enough, at the end the week, he claimed his prize.

His teams remain a tribute to a player whose swagger and speed personified audaciousness.

Since he arrived in Division I as Jackson State head coach in 2011, Fremin’s teams have led Division I in stolen bases seven times, including last season when eight players stole double-digit bases. Fremin’s teams led Division I in stolen bases per game six times, including four consecutive seasons at Southeastern from 2018-22 (excluding the abandoned 2020 season).

He got to Division I with Jackson State at the peak of the power revolution, just a year after Hawaii, of all schools, set a new NCAA single-season home run record and reached the World Series. By 2015, the year before he moved from Jackson State to Southeastern, Division I teams set a record that still stands by averaging 0.77 home runs per game. The long ball ruled. And if small ball wasn’t quite headed for the dustbin of history, like the baseball played in the deadball era, it was hardly the toolbox favored by most up-and-coming coaches.

There are practical reasons Fremin believes so wholeheartedly in the short game (in addition to all the steals, his Southeastern teams routinely come close to accruing twice as many sacrifice bunts as their opponents over the course of a season). He doesn’t eschew power and preaches balance. But the short game is his version of Moneyball.

“If I had all long ball hitters, and we just try and pitch it and go station to station, I personally think that’s boring—but at the same time, that may be somebody’s blueprint,” Fremin said. “Our speed game may be really difficult for them because they may give up lateral movement for a bomber in the offensive line up and maybe not be able to cover as much range—which is fine, that’s how they want to recruit. But they may not be a good matchup against our team, who is athletic and runs well and applies pressure.”

But even if that explains how Fremin’s teams succeed offensively, it’s not why they run. He doesn’t believe in a strategy. He believes in a mindset. Running isn’t who the Lions are. It’s how they express who they are.

Anatomy of a Lion

Someone like former Southland Conference Player of the Year Bailey Krolczyk makes it difficult to argue (for now) that Magee is the best player to call Southeastern home. But it’s similarly difficult to imagine someone who better embodies the program’s past, present and future.

After stealing 29 bases as a freshman, she’s on her way to even grander larceny this season. When she talks about the intricacies of leaving on time, tailoring slides to avoid tags, stealing off a catcher’s tendencies rather than the pitch and on and on, she sounds like someone who lives and breathes base stealing. And playing for Fremin, she more or less does.

Top 10

- 1New

Jaydn Ott

Top RB enters transfer portal

- 2Trending

Angel Reese

Reacts to Hailey Van Lith

- 3Hot

Nico Iamaleava

Odds out on next team

- 4

Hunter, Sanders

Colorado jerseys retired

- 5

J.D. Vance

VP drops Ohio State trophy

Get the On3 Top 10 to your inbox every morning

By clicking "Subscribe to Newsletter", I agree to On3's Privacy Notice, Terms, and use of my personal information described therein.

“Obviously, if you’re fast, it definitely helps,” Magee allowed. “But there’s a lot of manufacturing that will go into it—we work on reading and just anticipating, always being ready. We’re not having to get ready. So for example, if we’re on first, second, third—wherever we’re at—we’re always waiting for a mistake. It’s not reacting to a mistake and then you go, it’s like you are already imagining it happening and you never break stride.

“People see ‘Oh, another stolen base,’ but what they don’t see is that was weeks of practice when we worked on specific things for specific situations.”

Her high school coach, former McNeese State player Katie Roux Prescott, always told players that the best way to succeed was to fall in love with the process of becoming great. When Magee visited Southeastern, that’s what she saw. Maybe the stadium wasn’t quite as big. Maybe the history wasn’t as storied. But the players she encountered seemed to genuinely love what they were doing—at least as much as you can in the Louisiana heat.

“They seemed to be living that out,” Magee said. “No one enjoys sweating in the indoor whenever you’re hitting off the machine that’s throwing a pitch you’ve never seen in your life. But you know what? They did. They had the mindset that this is what’s making me great and I love that and I’m going to embrace that.”

It felt like a place where she could be big time.

“This is something great that’s being made,” Magee recalled thinking, “And I want to be a part of it.”

The image of Fremin sprinting down the third base line in last year’s regional, so close to the play at the plate that it was easy to think for a second that he might slide in after his runner, fits the profile of a bit of a control freak. (Indeed, he calls both sides of the game and estimates that he makes about 300 decisions in a seven-inning game.) But Fremin insists that Southeastern is a player-driven enterprise, maybe not a democracy but at least a constitutional monarchy. There is a leadership council for players—Magee was the lone freshman representative a season ago and returned this season. They suggest changes and set the tone in the locker room. And Southeastern players aren’t exactly inhibited when it comes to playing with joy.

The team begins each year with a beach retreat. Fremin and assistant coach Alana Fremin, his wife, have their say, but the trip isn’t really about them. It’s an opportunity for the players to take the lead. Magee was nervous ahead of the trip as a freshman, unsure about opening up. This season, with so many new faces, she helped put the foundation in place.

“I knew what they were feeling, so I was just trying to make them as seen and understood as possible without making them feel like I wasn’t listening,” Magee said. “We’re a team, and we’re here for each other no matter what. If you want it or not, I’m here regardless. That allowed us to grow in ways that are astronomically different than when we first stepped into our indoor facility. Now, you know the girls next to you better than any other players you’ve ever known in your life. That allows you to have the energy and chemistry on the field that’s incomparable.”

Moment or Movement

We’ve been here before in college softball, not so very far down the road in Lafayette. For much of the 1990s and early 2000s, the University of Louisiana (by whatever name) was the outsider that spent more time in the World Series than many programs with supposedly better pedigrees. Even after Gerry Glasco decamped for Lubbock, and 11 years after their last WCWS, the Ragin’ Cajuns continue trying to make Lamson Park a city-state among Power Four empires.

Can Southeastern use its old-school running game to turn back the clock?

As the publicity of last year’s postseason effort and years of success opens more doors, can it keep its culture while expanding its recruiting base?

Can it find more players like Magee, willing to follow a different path?

It’s only a handful of years since James Madison proved a mid-major route to Oklahoma City still exists. But setting aside Odicci Alexander’s singular presence, never more than during that postseason, the landscape of college athletics is barely recognizable across even a few years. From conference consolidation to NIL to revenue sharing and uncertain budgets, 2025 scarcely resembles 2021—let alone the Ragin’ Cajuns’ heyday.

More than a few people expected Fremin would be on the move after last season’s success, all the more with so many players moving on. He’s quick to credit school president Dr. William Wainwright and athletic director Jay Artigues for his continued presence in Hammond.

“If it wasn’t for those two men, and my faith and my wife and I kind of navigating through different things, we would not still be here,” Fremin said. “That’s the reason. It’s a special place: Hammond, America.”

While not an SEC palace, North Oak Park, the team’s home stadium, has benefitted from numerous enhancements in recent years. They also share a recently renovated training facility with the soccer team, complete with indoor turfed practice space.

And while neither Magee nor anyone else in the Southland is likely to match the sort of NIL money that helped convince NiJaree Canady to try and revitalize Texas Tech, Southeastern’s star shortstop has kept herself busy with grassroots NIL opportunities in the area.

“It almost feels like you’re one of the professionals, even though you’re not,” Magee said. “It’s surreal. You’re going and doing things that you see professionals do, but you’re living the college life. It’s unimaginable the joy you feel when you go and meet with a law firm and record videos and everyone is talking about it—and you’re still a little girl from Watson, Louisiana who is playing softball in Hammond, America. It’s something out of a movie.”

It would be naive to think there isn’t a version of this story in which Power Four schools come calling for Fremin, Magee or both—or at least their doppelgangers. That’s the way of the world.

Then again, asked by author Howard Bryant to explain his relentless audaciousness, Henderson offered a deceptively simple explanation.

“You have to keep running. I always believed I was going to be safe.”

Maybe there really is a program that believes big time will always be where you’re at.

Maybe they’re even right.