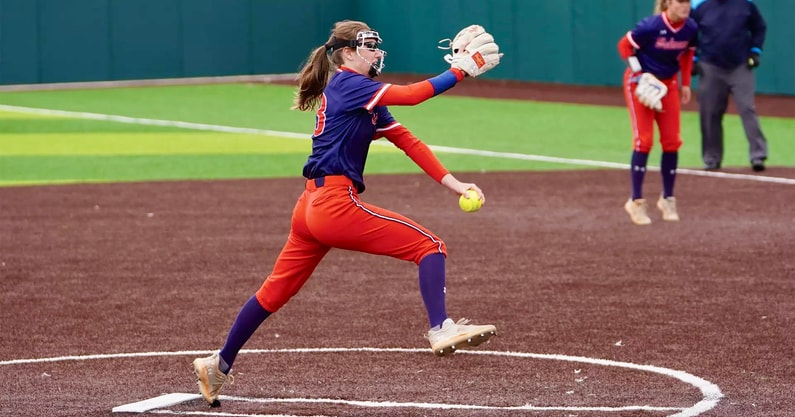

NCAA strikeout leader Maya Johnson driven to finish what she started

It’s not as if Belmont’s Maya Johnson doesn’t like position players. She’s surrounded by them. Many will be friends for life. It’s just that she doesn’t quite understand them. Not fully. It’s the part about investing so much time in the sport when the reward each game is walking to the plate a handful of times and fielding a few ground balls or tracking down the occasional fly ball. It sounds, well, a little dull.

For the senior nursing major, this isn’t complicated. She plays the game because she loves to win. No player has more influence over wins and losses than the pitcher. So, she pitches.

“I like the responsibility—the role that I play and the accountability I have for our wins and losses as a pitcher,” Johnson said. “I like to win and I like to be in control. I’m a little type A. I think that’s why nursing’s good for me. So I like being able to have a large hand in the outcomes of the game.”

She’s hardly the first pitcher to share such sentiments. She might be the only one who pondered them during an interview she was willing to schedule approximately an hour before her final undergraduate nursing exam. Then again, it made sense to squeeze in the conversation early in the day—you see, she was also working an evening shift at a Nashville clothing store.

“I’ve been bored out of my mind this week,” Johnson admitted of wrapping up the rest of her academic requirements. “I’m working tonight because I don’t like not doing anything.”

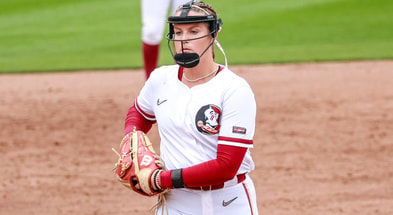

You begin to understand why it’s hard to get the ball out of her hand. Then again, why would Belmont head coach Laura Mathews try? In her third season, Johnson has gone from a mid-major ace with a head-turning strikeout rate to empirically the most dominant pitcher in the country.

Start with the traditional numbers, including a 22-4 record, 1.09 ERA and a Division I-best 320 strikeouts.

Move on to a nearly 18:1 strikeout-to-walk ratio—not just the best in Division I but nearly twice as good as any other pitcher. Megan Faraimo’s 14:1 mark in 2021 is the next closest over the past decade.

Admire the 2.6 walk percentage and 49.8 strikeout percentage.

Geek out with a -0.66 FIP, making her the only pitcher in the country in negative territory (usually reserved for the filthiest of baseball closers over very small samples).

But pause for an extra moment on Johnson’s 21 complete games. That’s a statistic with a story. In developing into a pitcher determined to go seven innings, Johnson is defying the sport’s prevailing winds. She’s an ace in a pitching world in which three of a kind is increasingly the winning hand. The philosophical shift is nothing personal. It’s just playing the odds. It’s risk aversion. Much as it was for the doctors who wouldn’t clear her to play when she was a freshman year at Pitt and the people who advised her to leave the sport behind. She sought a second opinion and left for Belmont instead.

“I’m pretty stubborn,” Johnson said. “I wasn’t going to let someone ruin my college career before it started. I am pretty determined. I wanted to play college softball. So I’m playing college softball.”

She was going to finish what she started. She still is, seven innings at a time.

It sure beats doing nothing.

Long Road to a First Start

Last season, even as she was emerging as an elite pitcher and throwing more innings than ever, Johnson often worked twice a week at Vanderbilt Children’s Hospital in the pediatric cardiac ICU, adding the 5 p.m. to midnight shifts to her other responsibilities.

Always pulled toward the sciences, maybe medicine and health care was always her destiny. But she ended up at Belmont, and working those shifts in the ICU, in no small part because of her own encounters with nurses.

Diagnosed with lupus during her sophomore year at Saint Joseph’s Academy in Ohio, she was the patient in pediatric units. Nurses would braid her hair, bring her snacks or sit and watch the Cleveland Browns with her. She eventually returned to the field and dominant form, able to manage the incurable illness with medication. But after experiencing serious lupus-related complications and another extended hospital stay, she wasn’t cleared to play as a freshman at Pitt in the fall of 2021. She recalls being told they would honor her scholarship, but they wanted to medically disqualify her, ending her career.

Hearing the words, she made up her mind to leave. She obtained a second opinion and Belmont provided a second chance—not to mention an acclaimed nursing program.

“Coach Matthews really took a chance on me and allowed me to come here when I had no stats in over a year to go off of,” Johnson said. “She knew me from the travel circuit, but I had nothing to go off of, nothing—like I had not picked up a ball in a year until that summer after my freshman year.”

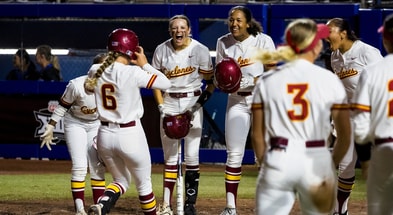

She struck out 10 batters in her collegiate debut in 2023. By the end of that season, she had two games with at least 20 strikeouts in the span of 10 days. She was just getting started.

Building a Finisher

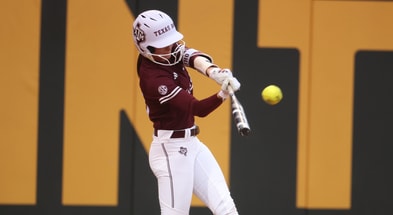

By any measure, Johnson enjoyed a breakout second season for Belmont in 2024. She lowered her ERA by more than a run to 1.49 and struck out 216 batters in 149 innings—enough to beat out NiJaree Canady, among others, for the best strikeout rate in Division I.

She hardly appeared to be running on fumes at the end. She struck out 35 batters in 19.2 innings across her final three appearances, including a one-hit shutout with 14 strikeouts in her regular-season finale. But held in reserve for Belmont’s MVC Tournament quarterfinal against Missouri State, she couldn’t save the day out of the bullpen when the game started to get away from the Bruins. The program’s first NCAA Tournament bid would have to wait.

That setback gnawing at her as the offseason began, the pitcher who limited opposing batters to a .196 average last season decided she needed to be harder to hit.

To increase her velocity, she followed a rigorous weightlifting program and added mass to a 6-foot frame. She went through exercises that targeted her maximum velocity, from long toss to rapid-fire speed trills to build quick-twitch muscle power. But while what the radar gun said under perfect conditions mattered, it was only part of the equation. How fast she could throw in the seventh inning mattered as much as what she topped out at in the first.

“I don’t think late in games, specifically, my endurance was as great as it needed to be,” Johnson said of facing batters for a third or even fourth time in a game. “When people were getting on, it was usually innings five, six, seven. I think some of that was I had a drop in velocity at the end of games.”

By intentionally scheduling bullpen sessions after her lifting and sprint work, she used the muscle fatigue to simulate how her body would feel in the later innings on a hot and sticky late spring afternoon—postseason weather, you might say.

“When you’re tired, that’s when your mechanics go,” Johnson said. “And if those to go out the door, you’re also not going to be throwing very hard.”

You’re also more prone to losing command or concentration when you’re tired. Johnson has never been a wild pitcher. Even coming off her long layoff, she walked 31 in 110 innings in her first collegiate season. That’s hardly profligate. But it bothered her that the walks seemed to come in a rush, losing hitters in four or five-pitch at-bats.

Between improved endurance and a redoubled emphasis on location, she’s walked more than two batters in a game just once this season. And her last five walks, all she’s allowed in the past month, came on full counts.

As a result, despite all the complete games, she hasn’t thrown more than 118 pitches in any of the 22 appearances for which pitch count data is available.

Top 10

- 1New

16-team playoff

Gaining steam in SEC, Big Ten

- 2Hot

CFB Top 25

ESPN shakes up rankings

- 3

Ben Christman

Cause of death revealed

- 4

Urban Meyer

Stricter punishment for lying to NCAA

- 5

Brandon Miller

Murder trial testimony revealed

Get the On3 Top 10 to your inbox every morning

By clicking "Subscribe to Newsletter", I agree to On3's Privacy Notice, Terms, and use of my personal information described therein.

She also spent the summer and fall working on her dropball. She started to get more of a feel for the pitch entering the 2024 season, partly out of necessity because of an injury that limited how often she could throw her horizontal breaking balls that offseason. But the drop wasn’t a pitch she fully trusted or commanded. It didn’t need to be.

In her first year as Belmont pitching coach, Emlyn Knerem was a two-time NCAA Division II All-American pitcher at Ashland University. She learned to throw a dropball when she was a kid but never felt comfortable enough with it to make much use of it in college. Looking back, she wishes she had. But she won 90 games with an ERA around 1.50 without it. She worked very hard at what she did well and had a great deal of success as a result. That’s the relatable story. That’s most pitchers, even good ones. Johnson isn’t most pitchers.

The result is that after allowing 11 home runs in 141.1 innings a season ago, a modest total in its own right for someone who throws the rise, she’s allowed just four home runs in 179 innings this season.

“Her screwball and riseball, especially as a lefty, are just really nasty for a right-handed hitter, but she wanted to get that last plane,” Knerem said. “She wanted to work down. We worked a lot on getting her movement, hitting that spot really well, being comfortable either throwing it in the dirt or at the knees. And I think that’s really what has manifested this spring, being able to go down in the zone and have another pitch.

“She’s just so good with all of her pitches, which it’s funny because we tell kids, ‘You don’t need six pitches to be successful.’ But here we are with someone who has six really great pitches. She’s an anomaly, to be honest.”

Zigging as College Softball Pitching Zags

It’s not the only way in she feels like one of a kind, or at least one of a vanishing few.

As Belmont settled into the week-to-week rhythm of conference play this season, Johnson told Mathews that even when she wasn’t needed in the circle on Sundays, she wanted to throw a full bullpen session. Understandably puzzled, her coach asked her why.

It was the best way to stay fresh, Johnson explained. That might sound counterintuitive. All right, that does sound counterintuitive. But hear her out. After excelling out of the gate this season, dominating the likes of Georgia Tech, Arizona State and Purdue in February, she hit what she described as a “dead arm period” and felt fatigued. She’s experienced similar stretches just about every year of her softball life, from high school and travel to now.

With increasingly ubiquitous jump plates and counter movement jump testing, she and the Belmont strength staff are able to more precisely monitor muscle fatigue and when to back off bullpens and when to go full throttle. She came through the dead arm (a relative term, given her continued success) and regained her velocity.

To her, the best way to make sure that lasts through the season’s most meaningful weeks has nothing to do with resting her arm. It’s all about using it. Fatigue is nothing to fear.

“I need to make sure that my arm is OK and prepared for that volume, and the best way to do that is throw complete games,” Johnson said. “Sometimes people think that a ton of rest is going to be the thing that helps. But personally, in my experience, when I have a ton of rest, my arm usually feels like it’s going to fall off. It’s honestly better for my arm recovery to have a more consistent volume than to have a ton of rest, then throw a game and be like ‘Oh my gosh, my arm is so sore,” because I haven’t thrown a game for a week and a half.”

Entering the final weekend before conference tournaments, Johnson was one of only five Division I pitchers with at least 20 complete games. After throwing just 13 complete games across her first two seasons, as she returned to pitching after her long absence and then worked back to full health, she’s finished 75 percent of her starts this season.

As recently as 10 years ago, five SEC pitchers had at least 22 complete games. Two decades ago, about the time Johnson was first picking up a ball, pitchers would with some regularity throw 30 and even 40 complete games in a season.

It remains to be seen whether Johnson is the reason for the softball establishment to reconsider how it manages pitchers. Good luck replicating the success if the model for extending starts is a long-levered lefty who can throw to with spin and precision to every quadrant—and who possesses a rich knowledge of biomechanics, nutrition and anatomy.

“Maya is probably the most unique pitcher I’ve ever worked with because she is so aware of what her body is doing,” Knerem said. “She truly knows better than anybody what her mechanics should look like and feel like. She feels everything in her pitches and in her mechanics.”

Not Finished Yet

It should come as no surprise by now that Johnson has already planned a heavy course load for her fifth year. The schedule is chock-full of chemistry and physics labs, among others, in anticipation of eventually attending medical school. She figures she’ll also pick up a nursing shift or two to earn some extra money. The team has a weekly day off, after all.

“I don’t think I know what it feels like to not be busy,” Johnson said. “I’m always doing stuff. People are like, ‘Why are you working a part-time job during season and doing nursing?’ I don’t like laying around. I don’t like it.”

It’s the same reason she doesn’t like sitting around in the dugout for the final few innings. She would rather be in the circle. She would rather finish what she fought so hard to start.

And with tireless attention to detail, the humility to get better and a healthy dash of sheer stubbornness, the most dominant pitcher in college softball is turning back the clock. Seven innings at a time.

More from Softball America:

Latest College Softball Bracketology

2026 College Softball Recruiting Rankings

SEC Tournament Central