Jenna Golembiewski, Chloe Parks honor their late moms by leading Miami forward

Jenna Golembiewski still has her mom’s instructions tucked away. She brings the letter with her to Oxford, Ohio, each year, packed alongside the softball glove, clothes and bedding. It reminds her how to handle the challenges ahead—collectively for a Miami MAC dynasty replacing starters all over the diamond and individually for a player replacing one of the most prolific power hitters in NCAA history atop every opponent’s scouting report.

Not that her mom could see the future. At least not in that much detail. LeAnn Kazmer Golembiewski didn’t get to see her daughter win three consecutive MAC tournaments or play in three consecutive NCAA regionals. She never knew Karli Spaid, for that matter, the All-American who was the Ruth to Jenna’s Gehrig a season ago. But the letter contains everything Jenna needs to meet the current moment, not to mention the far more consequential obstacles that inevitably await in a life beyond the softball field.

A basketball and track and field standout, Leann took time to warm to her daughter playing the bat-and-ball game. They battled, perhaps half-seriously, as stubborn moms and daughters do. But when Jenna went on a middle school retreat, she opened a letter that parents had been urged to write. Some things are easier left to pen and paper.

“I know we give each other a hard time about it, but I’d love to see you excel in softball. I’m so proud of you and how far you’ve come in softball and where you’re going to go.”

LeAnn passed away from breast cancer in 2019. But in those words blessing Jenna’s journey, she provided the advice that has served her daughter ever since.

Follow your own path. Be your own woman.

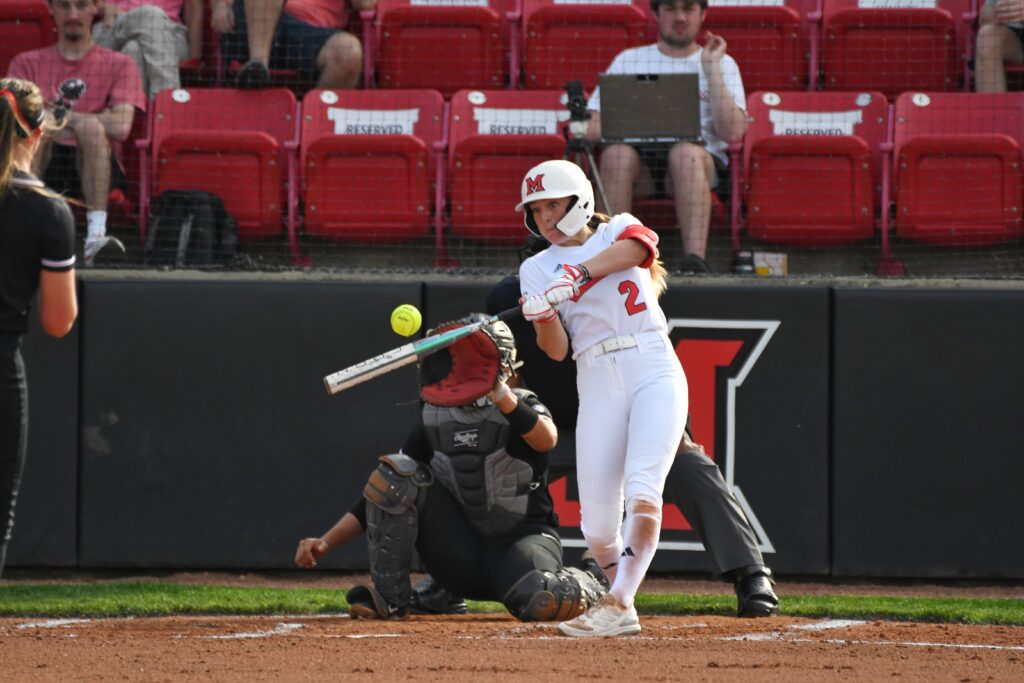

It’s how a freshman weathered a slow start to her collegiate career and grew into the slugger who hit 28 home runs in 2024—more than any returning player in the nation.

“Her hard work has paid off, obviously, but she is the most humble player that I’ve ever played with,” said fellow Miami senior Chloe Parks. “She has fun doing it. And that’s been so fun to watch. We’ve been with each other since freshman year, and to watch her grow, it’s been so freaking fun to be by her side and see it happen. She took her opportunity and she took off with it. And I love watching it.”

Sometimes loss is an all-too-painful catalyst for growth. Parks understands that better than most. Golembiewski’s teammate, roommate and friend for four years, she shares another bond, too. Stephanie Heinzelman Parks passed away in 2016 after a long illness. Her daughter was still in middle school. So much like her mom on and off the field, Chloe struggled to find joy in the game without her. But in time, she found that playing offered a way to honor her mom–and grow into the woman who would make her proud.

What’s next for Miami as the cast turns over following the greatest success in program history? Like any team, it will look to its remaining seniors for leadership. Two of them have more to offer than a few extra at-bats worth of wisdom.

They have everything LeAnn and Stephanie taught them.

“When you play for something greater than yourself like that, I feel like that’s something that’s really meaningful,” said Miami first-year head coach Mandy Gardner-Colegate. “They’re just both so mature and act with such grace, and I’m sure part of it is probably because of that traumatic experience. I’m just really glad that we were able to connect and able to coach them in their senior year because they’re both really special people.”

Two Moms Born to Play

There is ample statistical evidence for what kind of athlete LeAnn Kazmer was. Some of it is in the UNLV women’s basketball record book, where she still ranks in the top 10 in career field goal percentage, led the team in rebounding and blocks during one season and averaged double-digit points in each of her two seasons after arriving from junior college.

Still more is in the school’s track and field record book. A two-sport star (trimmed from an even wider portfolio in high school), she was the 1995 Big West high jump champion.

“Pardon my language, she was a badass,” Golembiewski said.

Stephanie Heinzelman left a historical trail, too. Her name is easy to find in the Roncalli High School softball record book. It’s right there, just down the page from current Florida superstar Keagan Rothrock—and a few spots behind Chloe in stolen bases.

“She was a stud of a softball player—third base-shortstop, lefty, fast as all get out,” Parks said. “Once I started gravitating toward softball, she was stoked. She wouldn’t miss a game. She was everywhere she could be. She was my No. 1 supporter.”

Stephanie never pushed her daughter to do more than Chloe wanted, but she couldn’t hide her competitive side, either. Chloe’s team practices were often only prelude to the marathon one-on-one backyard sessions that followed.

“She definitely taught me how to throw the ball—and to catch it,” Parks said with a laugh while recalling the sizzle on the balls coming her way.

Stephanie didn’t pursue college softball. Work and starting a family took precedence. But both she and LeAnn were children of Title IX’s second generation. They were the women who came of age during the 1990s—the decade of the epoch-making 1996 Olympics, the first FIFA Women’s World Cups and the Supreme Court decision in Cohen v. Brown. Sports empowered them and shaped them. Theirs was a world in which great disparity remained, but one in which so much more seemed possible. It was a world they were eager to pass on to their daughters through competitive sports.

Two Daughters Brought Together

Although they passed away before their daughters left for college, LeAnn and Stephanie are responsible for Jenna and Chloe putting up with each other as roommates for four years.

Soon after she signed with Miami, Jenna was scrolling social media to get to know the rest of her class. She stumbled across a blog post Chloe had written about her mom. Sobbing by the time she finished reading, she messaged her new teammates and shared her story.

At the time, it had only been about a year since LeAnn passed away. The wound was still fresh. And here was someone who understood everything she felt. Hardly a day passed without an exchange of messages. By the time the two of them arrived on campus, they weren’t just roommates but fast friends.

“Going off to college, it’s scary—you’re away from your family, all your friends,” Golembiewski said. “It was comforting knowing that there was someone who understood.”

They aren’t alike. Golembiewski is a power hitting outfielder. Parks is a slap-hitting infielder. Golembiewski is reserved. Parks is, well, not.

“She’s always chirping,” Golembiewski said. “That’s our dynamic at home, too. I’m always quiet, and she’s …”

Here Parks jumps in to finish the thought, “And I’m not.”

What they share in common, other than a competitive streak a mile wide, is a wavelength slightly out of range for those who haven’t experienced what they have.

On the hard days—the anniversaries, birthdays and Mother’s Day—they give each other gifts. But even in fleeting moments, a championship ring ceremony when other parents are part of the celebration, they’ll catch each other’s eye. They know. They’ve got each other.

Golembiewski knows to point out cardinals, redbirds symbolically meaningful to Parks because they stick out from the masses like her mom always did. Parks knows to return the favor with butterflies, honoring LeAnn’s wish that her children worry less about visiting a final resting place than feeling her presence in the sun, the wind or a butterfly’s flight.

Who Their Moms Made Them

Their mothers would have loved every minute of Golembiewski and Parks’ college softball experience—even if Parks is pretty sure more than a few umpires wouldn’t have similarly enjoyed Stephanie’s pointed feedback from behind the plate.

Top 10

- 1New

Michael Taaffee

Texas DB has surgery

- 2Hot

SEC fines Texas A&M

Faking injuries is costly

- 3

Tony Vitello

Vols coach spotted at scrimmage

- 4

UF Coaching Search

Two non-Kiffin names to watch

- 5Trending

Steve Spurrier

Reacts to Kiffin, Florida talk

Get the Daily On3 Newsletter in your inbox every morning

By clicking "Subscribe to Newsletter", I agree to On3's Privacy Notice, Terms, and use of my personal information described therein.

They would have loved the MAC championship celebrations and the intensity of NCAA regionals. But as former athletes from a time when the fight for equal treatment was only in its adolescence, they might have enjoyed nothing more than Miami’s visit to Oklahoma a season ago in the opening game at Love’s Field.

“Walking into a stadium and an atmosphere like that is something you dream of as a little girl,” Parks marveled. “Walking out of that tunnel and seeing it all, it was like ‘Wow, we made it.’”

Helping the Sooners break in their glittering gem of a stadium certainly ranks among the experiences Golembiewski and Parks will remember longest.

“The feeling caught me by surprise because I’ve never played in an environment like that,” Golembiewski said. “Once you step out there and you realize how big that stadium is, it takes you aback a little bit. I just remember standing there, looking around and thinking, ‘Holy crap, there are a lot of people here.’”

And yet the awe faded almost as soon as the first pitch was thrown. The Redhawks very nearly spoiled Oklahoma’s day, hitting two home runs to take a quick lead in the top of the first inning and then refusing to go away when the Sooners seized their own lead.

Trailing 7-3 entering the top of the seventh, Golembiewski hit the second of what would be back-to-back-to-back home runs that tied the game in stunning fashion. The person who started that rally? Parks led off that unforgettable top of the seventh with an infield single, typical of the understated influence she’s had across more than 150 career starts (including the walk-off regional home run below).

For much of the past decade, first under the leadership of Clarisa Crowell and then Kirin Kumar and her eye-popping offense, Miami wasn’t content with being a mid-major darling. It was a program that wanted to go toe-to-toe with anyone and everyone.

That’s still the goal under Gardner-Colegate, even if everyone is aware there will be growing pains when freshmen and transfers make up half the roster. The connective tissue between what came before and what comes next, Golembiewski and Parks are intent on passing along values that will shape seasons long after they are gone.

“We have team rules, team goals, team standards that are all the same,” Golembiewski said. “It doesn’t matter who the coach is, who the players are. This is Miami softball.”

There is a stubborn determination in the way Golembiewski says it. It’s who she is.

She says she doesn’t see a lot of her mom in her mannerisms and features.

“She could light up any room she walked into,” Golembiewski said. “She had this big blond, curly, beautiful hair, and she was like 6-foot-1 and showstopping. And I’m on the quieter side—I get that from my dad, shoutout dad.”

Other people see it, though. They tell her all the time that something she’s done or said reminded them of her mom.

The stubborn determination and competitiveness show up when she jokes that if her mom could be great in two sports, she ought to at least be able to hold her own in one sport. It’s how she went from six hits as a freshman to an All-American as a junior.

Maybe it’s even there when she’s short on patience—being a “tough piece of gristle,” as she puts it. That’s when her brother will look at her and tell her “I hope you dance.” It’s the song lyric she has tattooed on her skin, the song she and her mom shared during the illness.

“She had such a big personality that I don’t think I would ever be able to live up to that,” Golembiewski said.

It bothers her sometimes that she feels as if her mom only knew the “insignificant part of me,” the typically slightly self-involved teenager who seems to be pulling a face in every photo of the two of them together. She doesn’t think she’s that person anymore, occasional gristle notwithstanding.

Parks feels something similar, even more pronounced because she was even younger when she lost her mom. She recognizes much of her mom when she looks in the mirror, the fiery attitude and propensity to crack jokes and keep up a constant chatter, for sure. But also the commitment to do anything and everything for the people you love.

“I will always live and die by that path now,” Parks said. “My mom knew childish Chloe. I would still cry when I was mad. I would give them hell at that age. And that’s kind of how she knew me. I know it sounds cliché, but her passing has definitely influenced me to live life in the moment.

“Jenna and I always remind each other that it could be worse. Life could be so much worse. And life gets so much harder. It’s given me a new perspective and shaped me into a woman that I wish she could see—maybe a way different woman than I would have been.”

Miami softball? It’s in good hands. Two moms made sure of it.