C.J. Fredrick honors grandfather's legacy in return to Rupp Arena

Kentucky’s season-opening matchup vs. Howard will mark 595 total days between official game reps for redshirt senior CJ Fredrick — 19 months and change.

The longest absence of his basketball career began with a string of brief setbacks during his time at Iowa. He first cracked a rib taking a charge while redshirting as a freshman, then missed six games and two full halves in 2019-20 with a lower leg injury. That offseason, surgery to repair a fracture in his right foot. And then as a redshirt sophomore in 2020-21, he sat out four full games and missed time in three others as he battled plantar fasciitis.

Last summer, a stress fracture required him to have surgery and miss the entire preseason, paving way for a return in the Champions Classic vs. Duke to open the 2021-22 season. Then during pregame warmups, he exploded for a dunk and tore his hamstring, an injury that required yet another surgery — this one season-ending.

His debut campaign as a Wildcat was over before it even began.

“It was rough,” Fredrick told KSR in a one-on-one sitdown this fall. “Whenever you transfer to a new school, you want to come in right away and prove that you belong. I wasn’t able to really do that. I came in and got hurt within the summer, then came back and got hurt again. So I really wasn’t able to get my feet wet. Sitting out the entire year, yeah, it was rough.”

It wasn’t all negative. In fact, Fredrick says the injury was a blessing in disguise. Now down to 8% body fat, he was able to focus on getting in the best shape of his basketball career by drinking a few gallons of water every day, cleaning up his diet and becoming a daily sparring partner with the treadmill. It was also an opportunity to learn the game from a new perspective under a Hall of Fame coach in John Calipari, next to him on the bench rather than on the floor. He became a student of the game, getting a feel for the spacing and pace of SEC basketball, finding where he could make an impact when he eventually returned to the floor.

It allowed him to be “very much advanced” in what Calipari is looking for on the floor, all while pushing his body to its limits in an effort to come back stronger than ever. He wasn’t just competing with his teammates for reps, he was competing with himself, fighting to move past availability questions and finally show off his basketball gifts in Lexington.

To explain that drive, you’d have to go back two generations to find Fredrick’s why.

Papa Charlie

Charlie Fredrick had a knack for getting under his grandson’s skin. He did it better than anyone, understanding the obsessive competitor CJ grew to be — and he’s to blame (or credit?) for that. It’s in the Kentucky sharpshooter’s DNA.

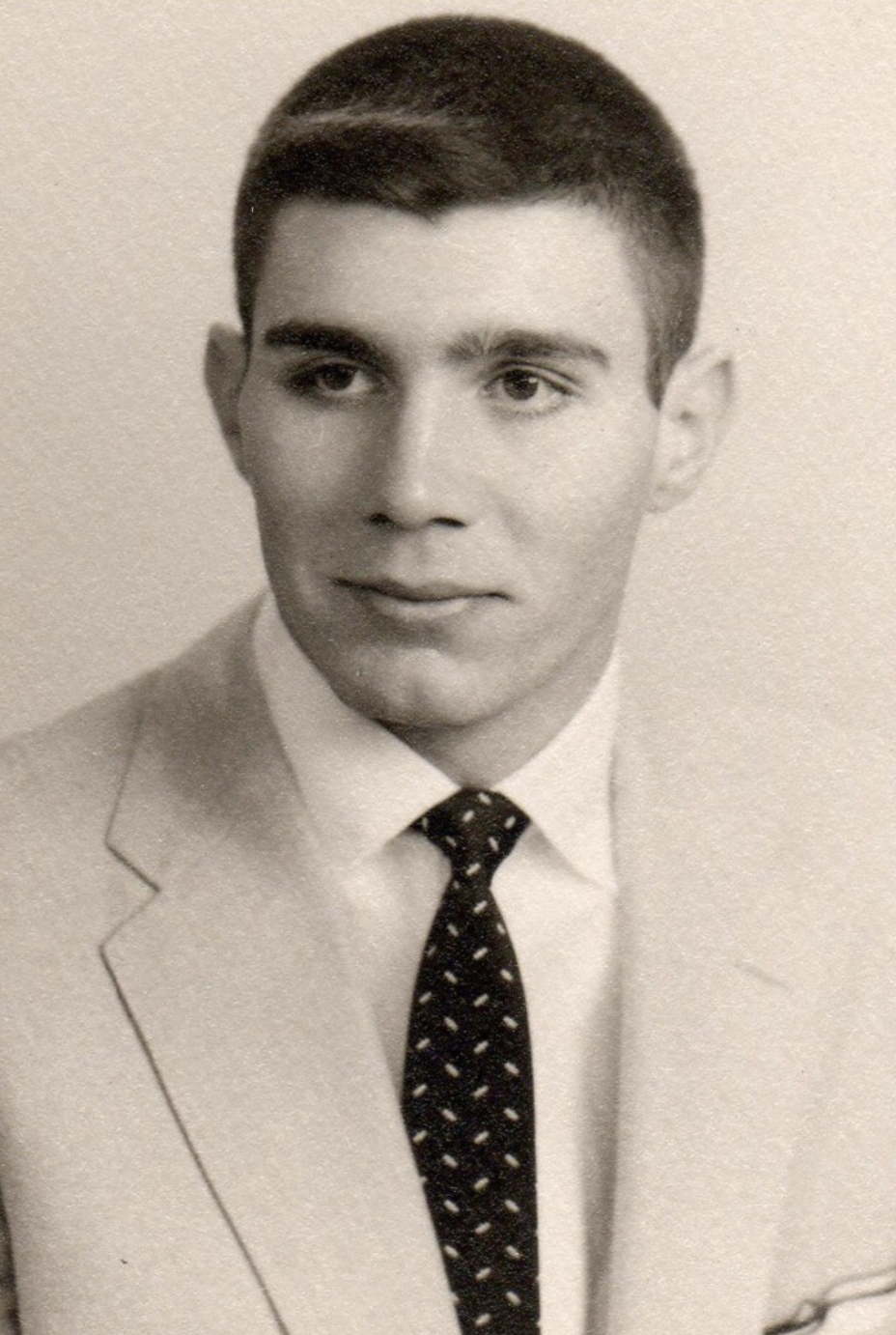

“Papa Charlie” was a star athlete at Newport Catholic HS, earning five varsity letters (three in football, two in basketball) before graduating in 1955. He went on to earn a football scholarship at Notre Dame, then found his calling as a coach and administrator in the Greater Cincinnati area. Fredrick started as a football and track coach at his high school alma mater, then spent a year at Highlands before making a permanent move across the river to Greenhills — now Winton Woods, the former home of UK football standouts Mike Edwards and Chris Oats.

He first coached, then was named athletic director in 1971, a position he held for nearly three decades. Retiring in 1998, Fredrick was later inducted into the LaRosa’s Athletic Hall of Fame and Ohio Interscholastic Administrators Hall of Fame, along with the Newport Catholic and Winton Woods halls of fame. Winton Woods would later name its football, soccer and track venue after him, Charles Fredrick Stadium.

“Everybody knew him,” Earl Edmonds, Charlie’s best friend and a Greater Cincinnati Basketball Hall of Famer himself, said. “He was just so highly respected.”

First as a player, then as a coach and athletic director, Fredrick dedicated his life to sports in the area. And that passion certainly didn’t skip a generation to CJ, as all four of Charlie’s children were standout athletes in their own right.

CJ’s uncle Joe followed in his dad’s footsteps to South Bend, a 3-point sniper on the basketball floor for the Irish from 1986-90, finishing his career as a 49.0% shooter from deep. His dad Chuck played basketball at Samford and Rollins, while his aunt Maureen played basketball at Xavier. Uncle Mike was a standout high school hooper, as well, leaving Greenhills as the program’s all-time assists leader.

Charlie soon became the patriarch of one of the area’s most successful sports families, and CJ was next in line.

Family rivalry

The Kentucky redshirt senior will admit he’s a bit of a sore loser, a learned trait that comes with being in a basketball-crazed family overflowing with fierce competitors. A one-on-one matchup in the backyard, a game of pool downstairs at grandma’s house or a board game at the dining room table, it didn’t matter.

If CJ lost, a temper tantrum was always a possibility.

“I think I was born with it, honestly,” Fredrick said. “Ever since I was little, I’ve just been so competitive — board games, anything. If I lost, I would make the biggest fit. I hated losing, and still today, I hate losing. It’s probably one of the worst things for me, I just do not like losing.”

He was a product of his environment, cutthroat with clear expectations of excellence. Settling for anything less was inexcusable, with accountability coming through in the form of tough love. It’s what almost ended CJ’s basketball career before it even began.

Fredrick struggled as a freshman at Covington Catholic (Park Hills, KY), where his uncle Joe serves as an assistant basketball coach. He was the seventh man on the freshman team, failing to make the JV team, let alone varsity. But he loved the game.

“He was just a normal freshman,” Covington Catholic coach Scott Ruthsatz said. “You could see something in him, but his development had just not happened yet.”

That offseason, he sat down with Joe and told him he was thinking about giving up football and baseball so he could focus on basketball, with dreams of playing in college one day. A former high-major Division I athlete himself, Joe told his nephew it was in his best interest to keep his options open.

Football, maybe, but basketball was a long shot.

“He was just kind of brutally honest,” CJ said. “He was like, ‘Man, I don’t know. … I don’t know if that’s gonna be the one for you.'”

He used to listen to his dad and uncle Joe bicker about who was the better shooter back in the day, a fight he hoped to join at some point. Aunt Maureen and uncle Mike had their own success, too. They’d all claim they were the best, an inevitable argument at every family get-together.

Papa Charlie’s accolades surpassed them all.

“At a young age, you see traits from your family and you want to be just like that,” CJ said. “You wanna be just as good as they are. As a freshman, I just wasn’t that good, and that would nag at me. My uncle would always tell me, ‘Oh man, I never played on the freshman team.’

“I wanna hold the legacy, I want to keep it going so bad.”

He begged uncle Joe to work with him, hoping his experience as a human flamethrower at Notre Dame would rub off and he could carve out a name for himself in basketball. That’s the sport he wanted to play, and he wanted to prove he could do it at a high level, just like the rest of his family.

Joe had his doubts, thinking at the time CJ didn’t work hard enough — he had been there in practice and saw the effort first-hand. His nephew wanted to be a DI player, but he didn’t work like a DI player. And that’s what he told him.

“I just told him he was not willing to do what it took to do that,” Joe said. “‘Like, I love you to death CJ, but I don’t think you have what it takes.’ … I remember the conversation vividly.”

Chuck stepped in and told his son there wasn’t any pressure for him to play, no matter the family history. He just wanted CJ to go all-in with whatever he did, he’d be proud regardless.

“My dad would be like, ‘You wanna play baseball? Play baseball. I’m gonna love you. If you wanna play the violin, go play the violin. I’m gonna love you regardless.'”

CJ chose basketball. And as promised, he pushed in all of his chips.

“I said, ‘OK, let’s go,'” Joe said. “And the kid showed up and did every single thing I asked him to do.”

Sophomore breakthrough

CJ lived in the gym that summer, the start of his transformation as a basketball player. He worked on his foot speed and the quickness of his release on jump shots, with conditioning a major point of emphasis, as well. He wanted to build up his endurance so coaches would have no excuse to take him off the floor, working with local trainers to help him get there.

The extra effort was noticed.

“He shows up sophomore year and he’s starting varsity,” Coach Ruthsatz said. “I’ve never had another kid do that, coming off the bench on the freshman team to starting varsity the next year. All he wanted to do was hoop. … Just an absolute gym rat, but the thing that stands out is his competitive nature. He was very competitive, never wanted to lose.”

“He was like a sponge,” Chuck added. “… I don’t recall saying to him one time, ‘You better get over there and work on your jump shot. You better get over there and get on the jump rope.’ He just did it.”

Covington Catholic had just gotten home after a blowout loss in Sarasota, FL. A step slow and running on fumes, the team jumped back on the bus for a three-hour ride on New Year’s Eve to take on Taylor County, ranked top-five in the state at the time and featuring high-major DI talent. CJ napped for two and a half hours — sleeping was a pregame no-no for the coaches — rolled off the bus and proceeded to play out of his mind.

He had 20-plus points in the first half, then finished with over 30, forcing Taylor County to throw the kitchen sink at him defensively. No luck. On the other end, he held Xavier signee Quentin Goodin to just nine points. It was CJ’s breakthrough moment as a basketball player.

“He just put on a show,” Joe said.

“I thought at that point he turned the corner,” Ruthsatz added. “Like, ‘This is a different player.’ … That was his coming out party.”

“I think that’s when everybody thought I could be something special,” CJ said.

Relationship with Grandpa

With greater play came heightened expectations. Covington Catholic fell to Charlie’s alma mater, Newport Catholic, in the state regional finals to end his sophomore season. His family gathered together back at grandpa’s house for pizza after the game, CJ mentally preparing for an earful.

“My grandpa was ripping me apart, calling me soft, said, ‘You’re not ready for this moment,’ all this and that,” he said.

That’s just who Papa Charlie was. That’s how he raised his kids, and that’s how they raised their kids. If you played poorly, you were going to hear about it. Nothing personal and completely out of love, but bluntly harsh nonetheless.

“My family is really about tough love,” CJ added. “If you didn’t play well, they’re not gonna sugarcoat it. ‘You didn’t play well.’ They’re not gonna sit here, ‘Oh well you had good passes,’ they’re not gonna do that.”

And that’s the way CJ wanted it. There was comfort in that approach, especially with his Papa Charlie. Their relationship was different, more like siblings than grandfather and grandson. Charlie would throw jabs and CJ would throw them right back. Charlie expected greatness out of his grandson, and CJ wanted to prove he was capable — and took great joy in following through.

“I wanted to be so good. … He would be the one to tell me, brutally honest, ‘Man, you’re not doing enough.’ I think that’s the biggest lesson I took from him, that I’m just gonna work as hard as I can and I’m not gonna let anybody tell me I can’t do something.”

He was like that best friend who always shoots with you straight, telling you what you need to hear, not what you want to hear. When CJ started taking basketball seriously, Papa Charlie took it seriously with him. And when it was time to rest and disconnect from the sport for a minute, he was there for that, too.

That’s when their friendship really started to blossom, right in the heat of high school.

“It was a loving, respectful relationship. At times, you would think they were two brothers,” Chuck said. “That might sound crazy, but after games, he’d say, ‘Hold on, I gotta go see Papa Charlie real quick.’ And they’d be over there yakking it up like a bunch of kids [laughs].”

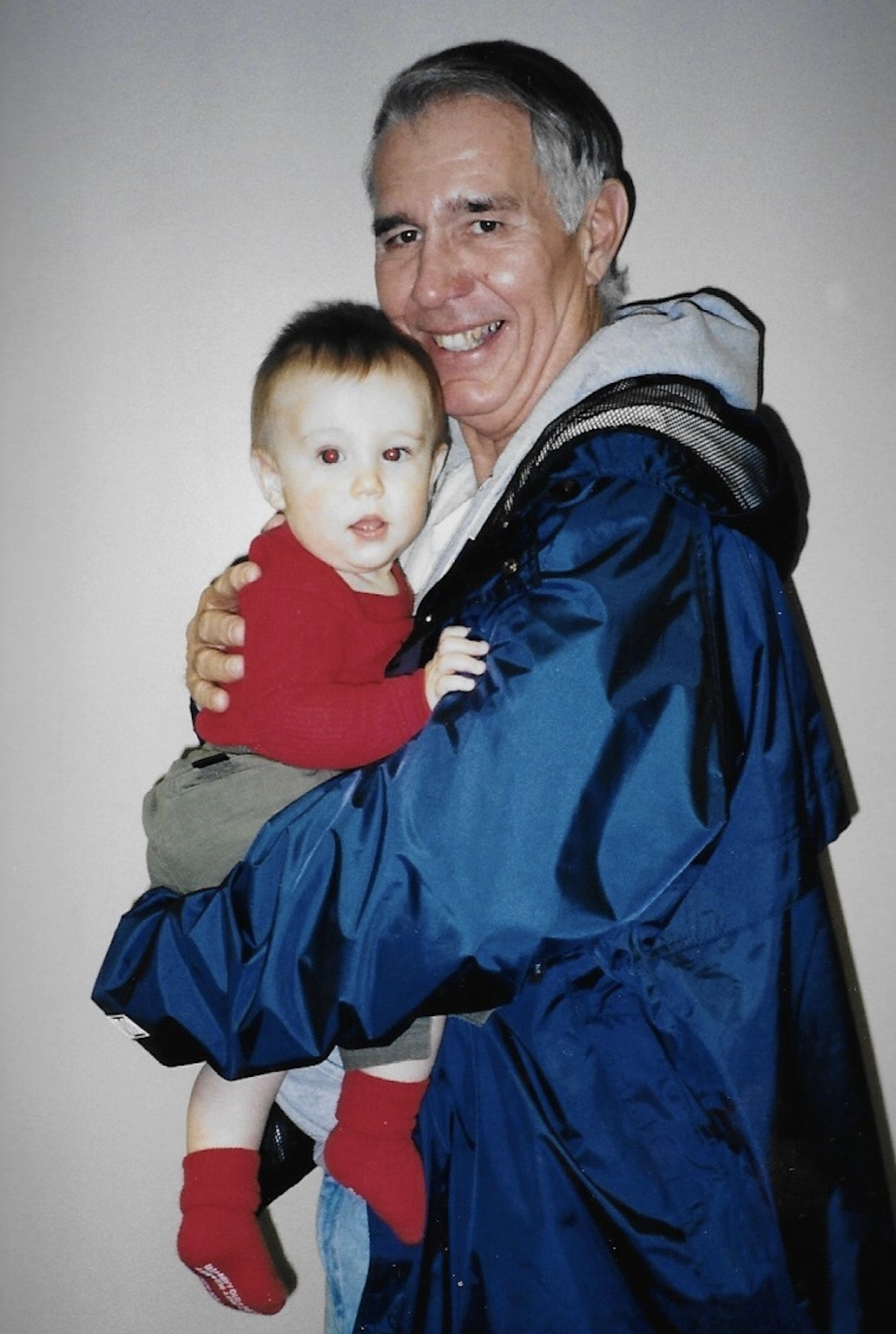

Charlie would text CJ in the morning he’d be picking some of the grandkids up from school, where they’d always go home, do homework, make dinner (or get Skyline and Graeter’s on special occasions) and go fishing in his backyard. It quickly became a family routine.

CJ’s phone would ring in sixth period, his grandpa telling him he was there to pick him up a whole hour before school let out. “And he knew,” CJ said, no matter how many times Charlie said it slipped his mind. The bell would ring, and there he’d be, waiting in the same spot under the flag pole with a bag of Chick-Fil-A in hand — a go-to treat of theirs to share on the way home.

“He would just be so excited to hang out with us,” CJ said. “Those are just the memories I’ll never forget growing up. He was my grandfather, but also one of my best friends.”

Grandpa’s house was also an outlet for basketball therapy when CJ needed it. Charlie lived just four miles down the road from school, so on nights CJ would have early practice or workouts, he’d spend the night with grandpa to ensure he was the first person at the gym in the morning. If practice was at 6 AM, he’d be there at 5:30 with his lights shining bright before sunrise so his teammates could see.

“Just to let ’em know that I was always there first,” CJ said.

He learned that one from Papa Charlie, too.

“Grandpa was huge. Charlie was huge in his development just as a person,” Coach Ruthsatz said. “They spent a lot of time together. … I think those memories are invaluable.”

CJ knew the decades of time his grandfather put in to earn the reputation he did in the area and the back-breaking work it took to get there. When Charlie said to work harder, it meant you needed to work harder. When grandpa stopped questioning his drive, he knew he was moving in the right direction.

“I get a lot of what I do from him,” he said.

A historic career at Covington Catholic

Chuck recalled the conversations his dad would have with his son leading up to the KHSAA Sweet 16 every year.

“Hey CJ, I’m going down and don’t know if I should book a hotel for four days,” he’d tell CJ. “Maybe we should go one day at a time.”

“You better get your hotel now!” CJ would respond. “You better book it for four straight days!”

The Newport Catholic loss ate away at the 6-foot-3 guard, especially knowing it gave Papa Charlie ammunition in their timely back-and-forths. Not only did he play “soft,” it came against his grandpa’s old school, a matchup the two had circled on their calendars every year. “Make sure you get there early to get a good seat so you can watch your Newport Catholic Thoroughbreds go down hard tonight,” Chuck remembered his son telling Charlie.

“CJ, I believe what I see, not what I hear,” he’d quip back. “Good luck, go get ’em.”

Then he lost. And then again in the regional finals the following year as a junior, this time an upset loss to Cooper High School.

CJ was sick that game, playing with a nasty bug that left him “wiped out, almost dizzy” after the loss, his dad said. He couldn’t even drive home because he was so physically and mentally drained. Chuck loaded him in the car and hit the road, where a loopy CJ proudly and confidently called his shot going into his senior season.

“I’m telling you right now,” he told his dad, barely able to string words together, “we’re winning the state championship next year.”

CJ’s work ethic “just took a whole nother level after that season,” he said. He was in the gym every morning, afternoon and night working to perfect his craft, locked in on one goal: “I envisioned getting to Rupp and holding up that trophy.”

Fredrick called it a “pretty solid season.” Anyone else would call it a superstar campaign, finishing the year averaging 22.5 points, 4.0 assists, 3.3 rebounds and 1.2 steals while knocking down 48.3% of his 3-point attempts (97-201) and setting the school’s single-season scoring record with 789 points.

He led Covington Catholic to a 31-4 final record and the 2018 state championship at Rupp Arena, as promised. It was a run that put the standout guard in the KHSAA record books, sitting at No. 12 in Sweet 16 history with 111 total points on 63.6% shooting (35-55) while hitting 10 3-pointers and 17 consecutive free throws. His 32 points in the title game vs. Scott County is ninth all-time in a single Sweet 16 game.

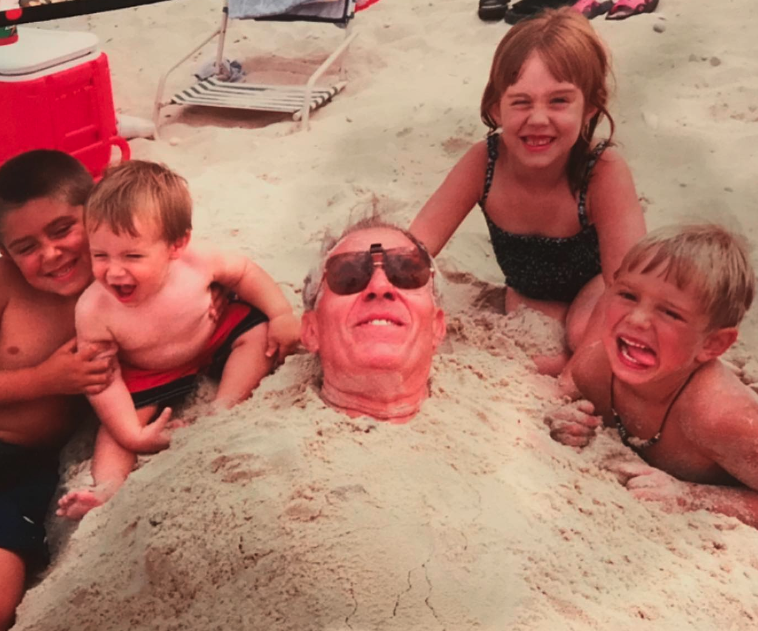

Papa Charlie was courtside for every matchup, using up every bit of that four-day hotel reservation in Lexington CJ recommended.

“He would go to as many sporting events as he could,” Chuck said of his dad.

Grandpa’s accident

Charlie was running a routine errand later that year, dropping off letters for his wife at the post office around the holidays. Like he’d done countless times in his life, he pulled into the parking lot and stopped his car in a spot. Certain his vehicle was in park, he opened the door and stepped out, only to realize he had left it a few gears short in neutral.

Sitting on a slight hill, his car slowly began to roll backward and pull him underneath, breaking bones in his back, ribs and legs, among other cuts and stitches. Before being transported to the hospital, he told paramedics to make sure they got the cards in the mail for his wife.

“We kind of knew after living wasn’t going to be the same for him,” CJ said. “But I didn’t – nobody expected that he would pass anytime soon.”

CJ was redshirting at Iowa at the time, right in the middle of the season. Initial medical feedback was that Charlie would be fine and an emergency trip home was unnecessary, especially for a freshman student-athlete looking to make a strong first impression in year one with coaches in workouts, lifts and other player obligations. Instead, his family back home would take shifts visiting with Charlie in the hospital every night, where CJ would call his parents or uncles to talk to grandpa, whoever was bedside at the time.

Grandpa’s tracheostomy restricted his speech, but he could write notes and make hand gestures — he’d always give a quick thumbs up when he heard CJ was doing well in his first year of school from Chuck or Joe.

When CJ called to check in, Charlie listened. He struggled to respond with words, but the air pushing through his breathing tubes let his grandson know he was there, hanging on to every word with attention and complete support. Just like normal.

Unaware of any potential sign of emergency back home, CJ was playing video games online with his cousin Mick when his uncle Mike entered the room in a panic. Through the headset, he heard his uncle break the news to his cousin that Papa Charlie had passed. And then his own phone rang, his parents calling to do the same.

Top 10

- 1Trending

MSU 83 UK 66

Spartans embarrass Cats

- 2Trending

Pope

Honeymoon is over

- 3New

National Media

takes on Kentucky's loss

- 4New

Pitino

weighs in

- 5Hot

3 reasons

MSU ran UK off the floor

Get the Daily On3 Newsletter in your inbox every morning

By clicking "Subscribe to Newsletter", I agree to On3's Privacy Notice, Terms, and use of my personal information described therein.

“It was a tough time because I couldn’t be there,” CJ said. “I still didn’t get to say goodbye to him or anything.”

83 years old at the time, he didn’t go without a fight, with doctors telling the Fredrick family they had never seen someone in his physical condition hang on the way Charlie did down the stretch. Broken bones and struggling for air, he fought until his very last breath — three months between his accident to the day he passed.

“He fought to the very end to make it,” Edmonds said. “He was just a competitor and he fought for his life.”

“Man, he was so strong,” CJ added. “Even his friends would always talk about how strong he was in college. I definitely get that from him, his mental toughness and what he did at the hospital. Doctors didn’t expect him to make it as long as he did.

“That’s just kind of everything our family stands for. He’s the backbone of our family, the strongest part of our family.”

Honoring Grandpa’s legacy on the floor

CJ noticed a theme following his grandfather’s passing. Every person he’d talk to about Charlie — friends, coworkers and former players — would say the same thing about him.

“‘Man, he was just such a great guy, you know? Humble, hard-working, doing things the right way. … Your grandpa was the best,'” they’d tell CJ. “That’s just who he is.”

Charlie’s nickname in the area was “The Mayor,” known for shaking hands with everyone in the room and delayed goodbyes — Chuck, Joe and CJ all joked you’d have to tack on an extra hour to whatever time he’d say he was leaving an event. As CJ got older, though, he realized how special that really was.

“There wouldn’t be a place we’d go to where someone didn’t know him or someone wouldn’t come up and say hi,” he said. “He was ‘The Mayor.’ He knew everybody, he talked to everybody and everybody loved him. His funeral was packed.

“… You kind of start realizing he had a serious impact.”

Humble. Hard-working. Doing things the right way. The traits and values Charlie was best known for are the same ones engrained in CJ from the start, how he goes about his business on the basketball floor.

It was never about scoring 30 points or making a certain number of shots in a game. Instead, Charlie pushed CJ to play a winning brand of basketball and help his team by doing the little things.

The points are great, but what about the missed free throws? What about the turnovers or defensive miscues?

“Dad always said, ‘The most important thing you do is you help your team win. You help everybody around you be the best players they can be.’ That sort of embodies what CJ is,” Chuck said. “When you watch CJ — and I don’t mean this as a negative — he might not be the tallest or have the highest vertical, but he’s pretty astute. …

“He isn’t this ‘wow, wow, wow’ kid up and down the floor all the time, but when you break him down, he just wants to win at the end of the day. It embodied my dad a little bit, just whatever you do, do whatever you have to do to win.”

“He’d tell me to play hard, dive on loose balls and play the game the right way. If you do that, everything will be fine,” CJ added. “That’s just kind of the way I play, I don’t like to force anything. I’m always gonna try to always play the game the right way. He was definitely a huge, huge part of who I am as a basketball player.”

Transferring to Kentucky

Sitting out his first season at Iowa, it didn’t take long for reality to hit CJ like a sack of bricks after Charlie’s passing, right in the middle of postseason play.

“I remember him saying, ‘You know Papa Charlie, he’s not gonna see me play a college game,'” Chuck said. “I said, ‘CJ, he’s gonna be watching you 24/7. He’ll be so proud of you.'”

CJ would go on to play two seasons for the Hawkeyes, where he emerged as one of the best 3-point shooters in all of college basketball, knocking down 46.6% of his attempts in 52 career games — all starts. After three years in Iowa City, though, he decided to explore his transfer options, looking for a school that could help take his game to another level to close out his career.

The competitor in him was craving more.

“What’s gonna help me be a better basketball player?” Fredrick said. “As a competitor at a high level, it’s always, ‘What can I do to get better?’ I knew that coming here would allow me to take a jump and to challenge myself and to get better. That’s what you want. You wanna challenge yourself and bet on yourself.”

He entered the portal strictly for basketball reasons. When those basketball reasons overlapped with some pretty significant personal benefits, Kentucky emerged as the clear choice.

“I’m 45 minutes away here, you know? My grandma can come watch me again. I can go home on Sundays and have dinner with my family. I can see my mom, I can see my dad, I can see my sister. This is just — this is a grand slam. Like, this is everything I could want.

“I’m gonna go to a place where I’m gonna be challenged, I’m gonna go to a place where expectations are super high and perfection is a must. I’m gonna go to a place where I can win and I’m gonna be close to home. It was perfect.”

And not only will the program help him, he’s going to help the program, as well. After all, 3-point shooters like CJ don’t just grow on trees.

“It’s a great move. … He’s put himself in a position where he can really help the team,” Coach Ruthsatz, who CJ calls “one of my favorite coaches I’ve ever played for,” added. “The game has evolved at all levels. You have to be able to shoot the ball, and he’s an elite shooter surrounded by elite athletes and quick guards.

“He’s gonna draw a lot of attention. You cannot leave him open, he just shoots at too high of a clip.”

The move would have gotten Papa Charlie’s stamp of approval, as well, his best friend is certain.

“He loved him dearly. Charlie was just so proud of that young man and the success he had,” Earl Edmonds said. “And, CJ is a great kid, just outstanding. I know how much Charlie loved that boy and he would be so proud of him going to the University of Kentucky.”

Making an early impact

His presence has already been felt to open his Kentucky career — a year late, no thanks to his brutal run of injury luck. Making his unofficial debut in the Bahamas this summer, John Calipari had an individual highlight segment made for Fredrick during a private film session breaking down all of the ways he impacted winning in his first game alone.

That was in a zero-point, one-attempt performance for the redshirt senior.

“I may be on your ass, and then the next day, ‘I was wrong. I watched the tape and you were right. You were better than I thought,’” Calipari told the team. “Well, CJ, I watched him — I mean, come on.

“… He did good. His first time out, too. I said, ‘Wow.’ He was hungry.”

“We showed you guys the star — and you could see it on film,” assistant coach Chin Coleman added.

Jump ahead to the preseason, where the gushing continued for Fredrick.

“The other things he does. He moves his team, he plays so hard, he talks on defense,” Calipari said following Kentucky’s first exhibition game. “… It’s nice when you have older guys that really know what they’re doing out there. He’s special.”

And that’s on top of his abilities as a coin-flip 3-point shooter.

Through the adversities, CJ’s patience and persistence paid off. He found a winning partnership in Lexington that benefitted both sides.

“At the end of the day, it’s about winning,” Chuck said. “It’s about bringing value to your team, making your teammates better. I can just remember my dad echoing that, and CJ embodies that. He’ll play tough D, he’s a willing passer, he’ll take the shot when he needs to. But I think most importantly, when things get tough, that’s where CJ seems to excel.

“In big moments, it always seemed like CJ got a good stop or took a charge, made a pass or hit a big clutch shot, you know?”

Returning to Rupp Arena

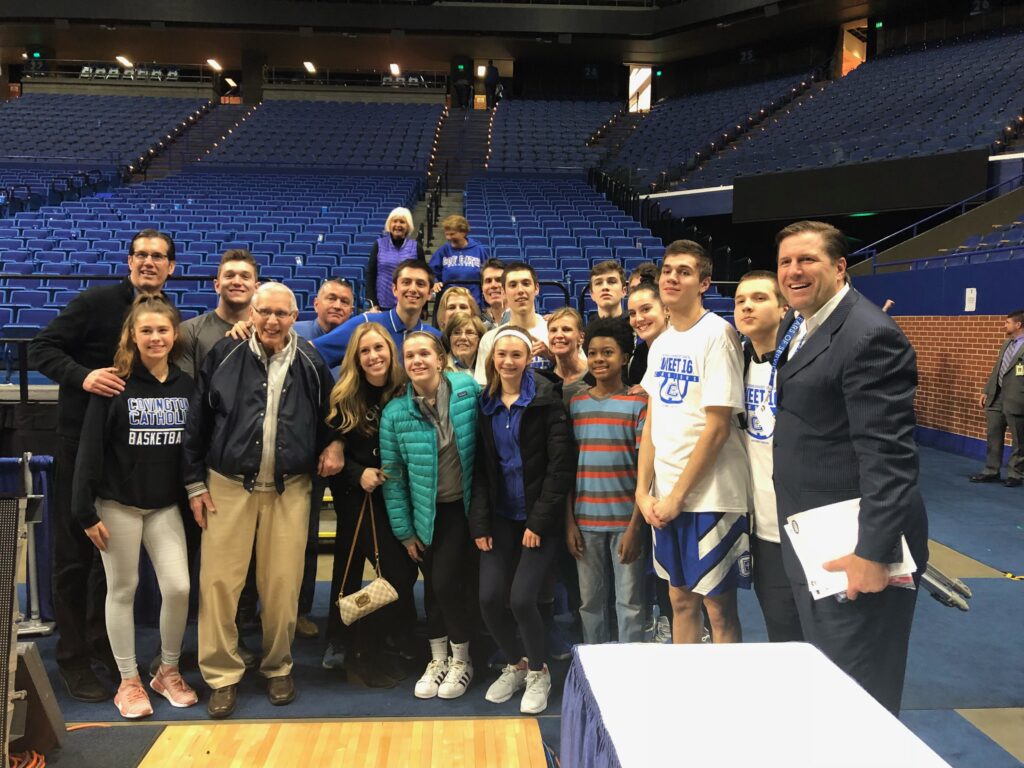

Chuck remembers taking CJ to Lexington after he made the decision to join the Kentucky program last offseason, touring the facilities upon their arrival. The Fredricks walked out of the tunnel at Rupp Arena and onto the court, soaking in CJ’s new permanent basketball home while also reminiscing about CovCath’s state championship run in 2018.

Then CJ remembered his grandpa.

“I started looking around and said, ‘I wonder where we were sitting during the Sweet 16,’ Chuck said. “And CJ looked over at me and said, ‘That’s where Papa Charlie sat, right there.’ He remembered the actual seat, the location. I thought that was pretty cool, I couldn’t even remember that.”

Fast forward four long, adversity-filled years, and CJ is finally set to return to the floor where that magical run took place for his first official game as a Wildcat.

It’s also where he played his final game with his beloved grandfather in the stands.

“That 2018 run was really special, we had a great group of guys and great coaches. My grandpa, that was the last place he watched me play,” CJ said. “Going back out and being in front of fans, seeing how they were like last season, it’s gonna be a special moment for me, that first game. I really look forward to it.”

How proud would Papa Charlie have been seeing CJ run out of that tunnel again for his official Kentucky debut, back where it all started?

A long, silent pause followed, seconds dragging on as his father gathered his thoughts.

“Well, that’s a good question,” Chuck said, voice cracking with every syllable.

He let out a heavy sigh, followed by another long pause. “I’d say if he was still living,” he said shaky and carefully, fighting through tears, “it would probably be just a big hug after the game.”

The 19 emotional months CJ spent clawing his way back to the floor rushed through his father’s mind, the painful setbacks and time away from the game his son so desperately loves. Then he saw his own dad, who gave CJ that love for the game to begin with, spending every waking moment of his life supporting him on his journey.

“I’d say he’d give him a huge hug, say, ‘I’m proud of you, keep grinding. Help your team win a championship. Whenever the next game is, I’ll be here.'”

Charlie won’t be courtside like he has been from the beginning, where he last saw CJ take the floor for a game, leading his team to a state title at Rupp Arena. Physically, at least.

But keep an eye on CJ when the National Anthem echoes through the historic venue’s loudspeakers, or even after the game at the final buzzer. You’ll notice a subtle tap on his right forearm, where his grandfather’s legacy lives on.

There, a tattoo featuring Papa Charlie’s heartbeat taken from the hospital monitors during his late fight, along with the date of his passing: 3/8/19.

“Even though he’s gone, he’ll always be living through me,” CJ said. “It just reminds me he’s still there and I still have him with me wherever I go.”

Discuss This Article

Comments have moved.

Join the conversation and talk about this article and all things Kentucky Sports in the new KSR Message Board.

KSBoard