The Reed in Reed Sheppard: Stacey's Story

[Ed. Note: With the news that Reed Sheppard is headed to the NBA Draft, we’re bumping this feature from November up.]

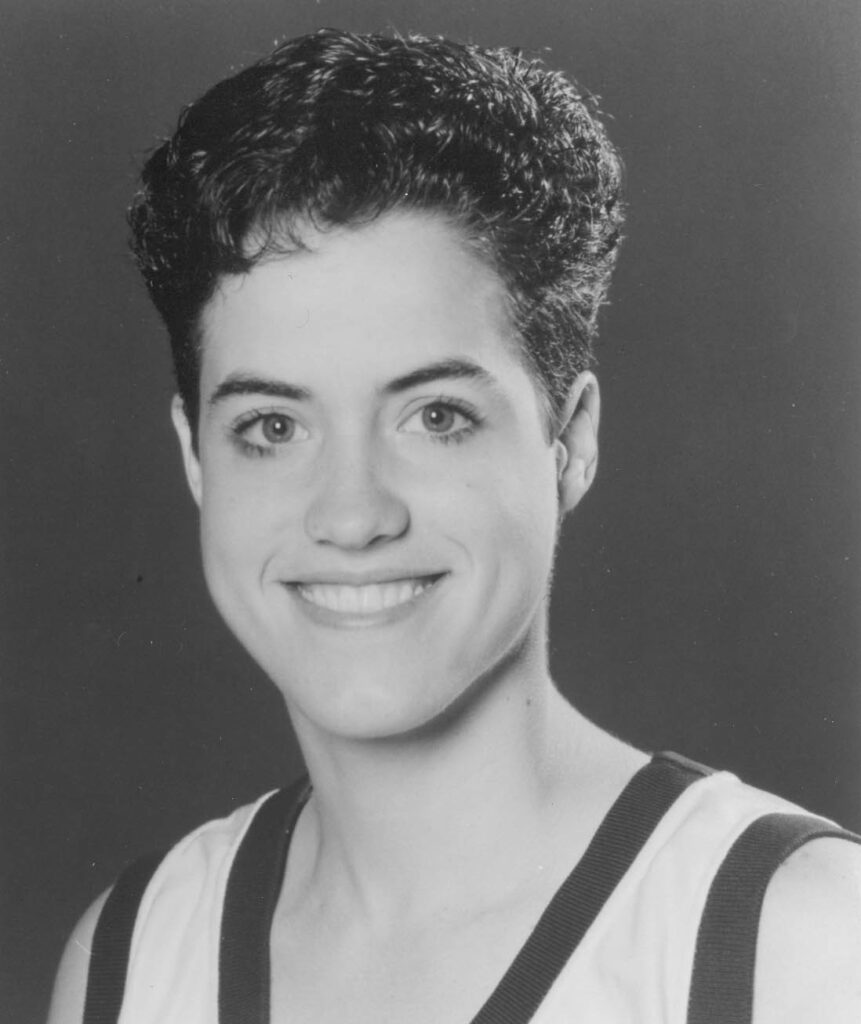

Even with his famous lineage, it would be hard to script a better start to Reed Sheppard‘s college career than what is currently unfolding in Lexington. The son of Kentucky Basketball greats Jeff and Stacey Sheppard leads the nation in true field goal percentage (87.2), 3-point percentage (63.3), and overall plus/minus (+17.4 per game) through seven games, all as the Wildcats’ sixth/seventh man. As Reed stepped into the spotlight for an injured DJ Wagner on Tuesday to lead No. 12 Kentucky to a 95-73 thumping of No. 8 Miami, the college basketball world buzzed about the legacy kid from Eastern Kentucky, a story almost too good to be true.

On a local level, Reed’s start feels almost mythical. His first official points in a Kentucky uniform came off a dunk, which conjured memories of his father’s high-flying days as a Wildcat. Images of father and son dunking in matching No. 15 Kentucky jerseys went viral as generations of fans bonded over a dream realized. He’s just as good as his dad! A few games later: Wait, he could be even better than his dad! Now: Let’s enjoy him while we can.

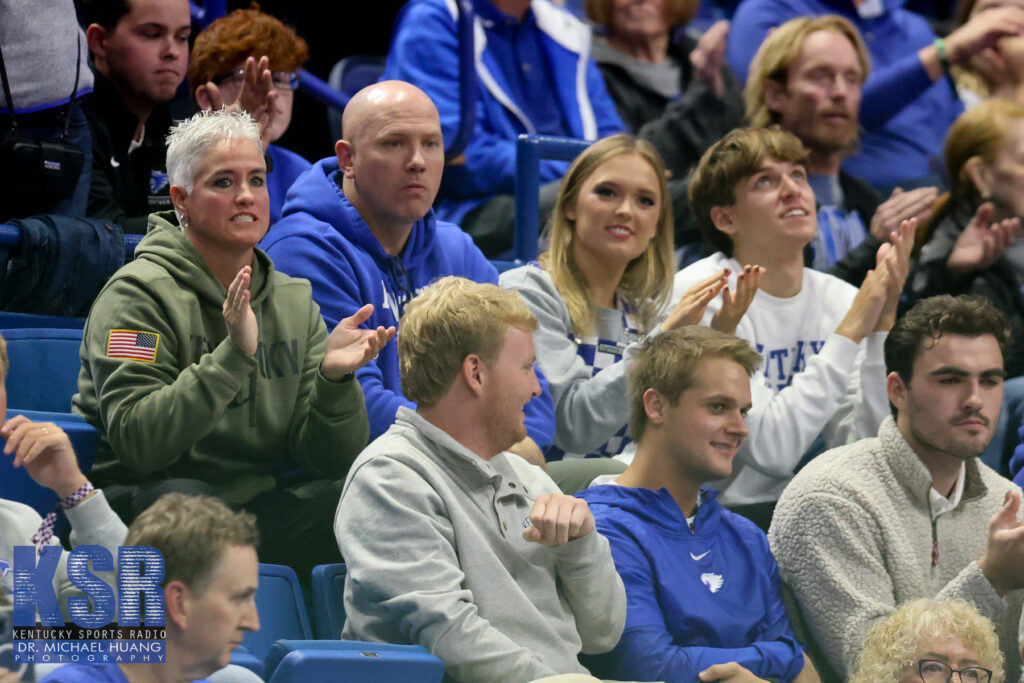

“Jeff and Stacey Cam” has become a staple on broadcasts, with the TV camera finding them after almost all of Reed’s big plays. More often than not, the commentators mention Jeff, the two-time national champion and 1998 Final Four MVP; the people who know mention Stacey first.

Stacey may not have a championship ring like Jeff but her name, Stacey Reed, is all over the Kentucky Women’s Basketball record books. She still ranks in the top ten of several statistical categories and is the program’s all-time leader in steals per game (2.7), fourth in assists per game (3.9), and seventh in three-pointers made (175). Right now, her son leads the SEC in steals per game (3.1) and is second on the team in three-pointers made (19) and third in assists per game (3.6). He’s also fifth nationally in steal percentage (6.91%), the percentage of possessions a player records a steal while on the court.

“Everyone from home is like, you play like your mom,” Reed Sheppard said. “She played the same way. And then some people that don’t really know mom, they just fall onto I play like my dad because that’s all they know.”

The difference is in the hands, which John Calipari has said multiple times may be the best he’s ever coached in his 32-year career.

“His hands, his feel, he plays exactly like his mom Stacey,” Calipari said after Reed’s standout performance vs. Miami. “Just like her. The way he gets hands on the ball, steals, and feel and all that stuff. Jeff could score. Didn’t have the body that this kid has.”

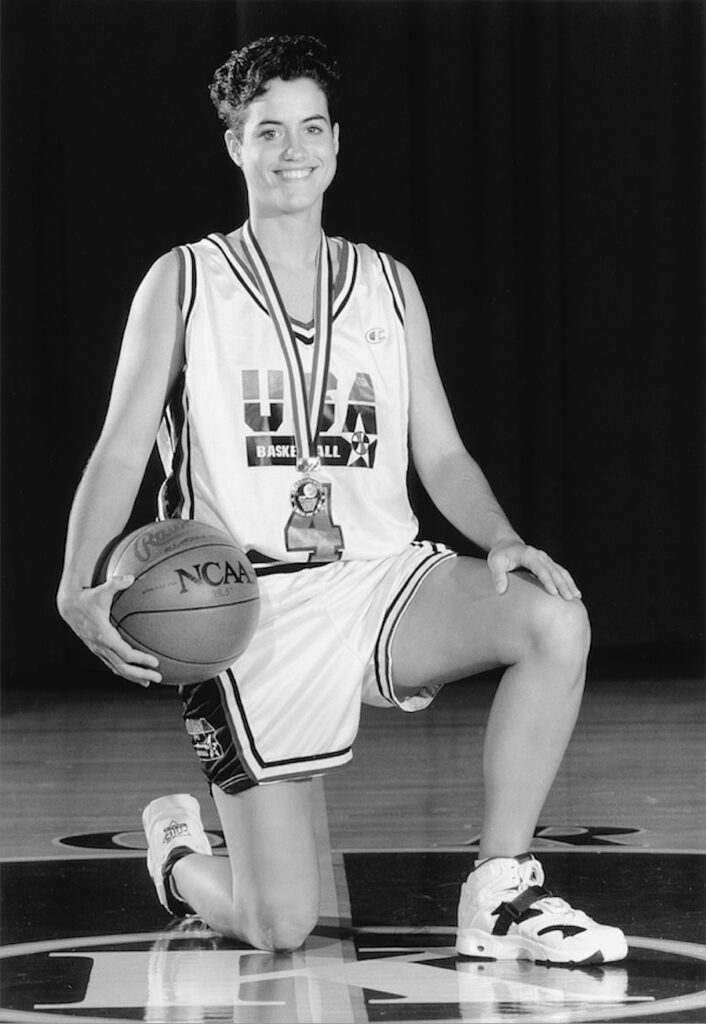

Footage of Stacey during her time at Kentucky is scarce and the pictures are all in black and white, which, she ruefully points out, is a sharp contrast to the many color pictures of Jeff, whose career started just a few years after hers. However, you don’t have to look far to imagine what it was it was like to see her play.

“What was it like watching her?” Jeff Sheppard said. “Watching a 5’7” Reed Sheppard out there is what it was like.”

A simple slab of concrete on a farm in Laurel County hosted countless basketball games in the 1980s, with stars ranging from Larry Bird to David Robinson, Sam Bowie, Dirk Minnified, and Kyle Macy. In place of the towering figures was a young girl, racing back and forth, her frenetic pace only matched by her imagination.

“We lived on a farm and there wasn’t a lot to do, so you had to entertain yourself some way, so that was my entertainment,” Stacey Reed Sheppard said. “I would impersonate who I wanted to be. I was the players, I was the commentator, I was the scorekeeper.”

“She would be outside playing basketball, pretending that she was one of the superstars,” Lola Reed, Stacey’s mother said. “We didn’t have anything real fancy at our house. But we did have a big concrete pad and a basketball goal. And that’s what she did all the time.”

Stacey’s father Mike played in an intramural basketball league in town from the time he and Lola married until he was 65 years old. Growing up, Stacey always accompanied him to games, jumping at the chance to play on the concrete courts and hear her shots clink through the chain net.

“On those courts, at those games, is where I fell in love with basketball,” Stacey said. “As a little girl, or little kid in general, when you’re playing with adults, they’ll kind of just roll the ball to you, as not to hurt you or anything. And that would always make me mad. I’m like, ‘Just throw me the ball!’ So I had to learn pretty quick to fight for what I wanted on those courts.”

“You have to understand, when she was young, she was tiny,” Lola said. “Had such tiny structure. So petite looking, and just looked like she would break. They were just afraid they would hurt her. It didn’t matter to Stacey. She would do it anyway. That’s just how Stacey is.”

Stacey joined the Laurel County eighth-grade team as a first-grader. From there, her time on the court only increased, with Mike providing instruction.

“They played and he never would let her beat him,” Lola said. “That was his philosophy.”

“From that point on, it was just – it was my passion,” Stacey said of basketball. “It’s what I loved. It was where I was at peace, on the court. I could get away from everything.”

The legend of Stacey Reed started to spread through the mountains. A Kentucky fan who grew up in the area recalls an eight-year-old Stacey beating her in a skills competition by 150 points. Another was a tee-ball umpire in London who said the opposing coaches would groan when Stacey took the mound. “She would send it over the fence every time.” And then, there was football.

“She can throw a ball as good as anybody,” Lola said. “They always chose her on the teams when she was in middle school, elementary, all that.”

“I’m a huge football fan,” Stacey said. “I would have given my right arm just to play football.”

That didn’t really happen back then, so Stacey channeled herself into basketball. She watched every Kentucky game that was available on the three channels on their television. She got to meet Melvin Turpin and Sam Bowie, which only increased her passion for Kentucky Basketball. Dicky Beal, Derrick Hord, Roger Harden; you name them, she studied them. That said, one figure stood above them all.

“Out on the court, I wanted to be Larry Bird,” Stacey said. “I loved Larry Bird.”

“I had all his posters hanging in my room. So out on the court, I would try to emulate some things that he would do. And, of course, I would always get fouled if I missed the shot. But it was just fun. It was just me in my head out on the court.”

Stacey won two state titles at Laurel County, the first as an eighth grader in 1987, and the second as a senior in 1991. As she gained more experience and exposure, she reached out to Patty Jo Hedges, a standout at Louisville Western High School who became Kentucky Women’s Basketball’s all-time assists leader, a record that still stands.

“I was like, ‘Okay, I can do that,'” Stacey said of watching Hedges. “Her confidence and encouragement in me was also a big part in just staying motivated and doing the things I knew I could do and do well and not try to be more than what I was.”

Hedges and Stacey communicated regularly through Stacey’s high school years, but it wasn’t until Stacey attended the Blue Star Basketball Camp in Chapel Hill, North Carolina that she realized her basketball dreams could extend beyond Laurel County.

“I had one of the best weeks of camp of my life. And after that camp, I started getting all kinds of letters and stuff from different colleges. And I was like, ‘Wow, I might have an opportunity to play basketball after high school,’ which I’d never thought of that. It was not something that I’d thought of.”

Stacey received interest from a lot of colleges, but two stood out to her the most: Western Kentucky and the University of Kentucky. She played one of her state title games at WKU’s arena and was leaning toward the Hilltoppers despite her love for Kentucky. She took a recruiting visit to Lexington and, as a self-professed “little girl from the country,” didn’t really enjoy the experience. The Cats continued the full-court press, even getting Rick Pitino involved to hopefully seal the deal.

“I’ll never forget that phone call that morning,” Lola said. “He called her and told her, ‘Tracy, we would really like to have you come to UK.’”

“My reply to him was, ‘Hello, Dick!'” Stacey quipped.

“From that point on she was never a fan of Pitino,” Lola said. “Not anything else but just because he didn’t know her name right.”

Despite Pitino’s call and the country-mouse-goes-to-the-city hesitations, Stacey knew where she belonged.

“When it came down to it, I knew that I wanted to experience what I had watched my whole life growing up, being at the University of Kentucky. I wanted to be a part of the history and the culture of Kentucky Basketball.”

When Stacey arrived on campus in 1991, it didn’t take her long to make her mark. She ranks in the top ten all-time among freshmen in field goals attempted (266), three-pointers made (30), free-throws made (62), free-throw percentage (74.7%), and steals (69). That latter mark is second in program history behind only A’dia Mathies, who tallied 93 steals in her first season in Lexington (2009-10).

Stacey also stepped up as a leader, proving herself to her teammates on and off the court. Her work ethic in practice was second to none and she also stayed behind to do “whatever needed to be done for the team,” whether it was picking up cups or taking jerseys to the equipment room.

“You’ve got to talk the talk and walk the walk,” Stacey said. “You have to get everybody to believe in you, not just the coach, but your teammates as well…Just let them see that I’m not just speaking what I’m thinking but I’m also living what I’m saying.”

Sharon Fanning was the Kentucky Women’s Basketball coach from 1987 to 1995, which included all four of Stacey’s seasons. Fanning continued her career at Mississippi State, coaching the Bulldogs’ women’s team for 17 years. She retired in 2012. All these years later, her memories of Stacey remain crystal clear.

“She loved the game as much as anybody I’ve ever coached and had as sweet a jump shot,” Fanning said. “Up and down on a dime. Could go by you. Knew how to get past people, pull it up, to get it to the rim. Had good range. And had the ball-handling skills to get away from people. She loved it.”

Sean Woods, one of The Unforgettables, was a senior at Kentucky when Stacey was a freshman. He will never forget Stacey challenging members of the men’s team to pick up games at Memorial Coliseum.

“She was a bulldog,” Woods said. “She was feisty and super competitive and wanted to play one-on-one. She was one of those girls who knew when to jump in. She has a beautiful personality, but you could just tell just her competitive juices. She had it from a competitive standpoint.”

“I can see her breaking down to guard somebody,” Fanning said. “I can just see it still, in my mind. If she would do something or if she would mess up or something, she would slap her leg with her right hand. She would slap that hip when she’d mess up or something or foul. She’d have that look on her face, that ticked-off look.”

As mentioned, there isn’t much footage of Stacey from her time at Kentucky. Her children, Reed and Madison, have only seen glimpses through old newscasts.

“There’s one video that I’ve seen,” Madison said. “She hits this shot, and she like jumps up and does this twirl in the air.”

“I haven’t gotten to see much,” Reed said. “I’ve seen a few clips here and there. I wish that I could watch a game or two of hers just to see how she played.”

When it comes to distinct memories of Stacey, one stands out for Sharon Fanning. Kentucky was hosting Western Kentucky at Memorial Coliseum during Stacey’s senior season. The program used to honor different areas of the state at each game, and for this one, Laurel County was in the spotlight. Stacey was able to invite some of her family and friends from London to sit behind the bench as guest coaches. It was also the first time the Kentucky pep band performed at a women’s basketball game.

“I can see the smile on her face,” Fanning said. “She would always be up front, bringing the ball out with the team on the floor. I can still see that big old smile when we had a band for the first time. That was a pretty special time to see her so excited.”

“It was just another day have a sense of pride that my family, my hometown people were able to be at that game,” Stacey said of the day. “And then you had the band, which brought a whole other level of excitement. And so running out on the court at that time and hearing that and just the pride of Kentucky just coming through, that experience in itself was really special.”

“Her heart, I guess you could say, is like Secretariat’s,” Fanning said. “It’s bigger than most. Just a winner. If you look her name up and you saw it in the dictionary, you’d have ‘Winner’ by it.”

Throughout her college career, Stacey also played for USA Basketball, representing the United States on several foreign trips. She played on the USA Junior Select team in the summer of 1992, won a silver medal as a member of the World University Games team, and took home gold in the Jones Cup in Taiwan. She returned to Taiwan after her senior year, but the experience was short-lived, to say the least.

“When we got over there, the team that I was supposed to play for decided they didn’t want an American player. So I had packed my bags to go for six months and I was there for eight hours and they sent me back home. So I sat in the airport in Taiwan for over 24 hours by myself with all my luggage.”

There was, of course, another central figure in Stacey’s time at Kentucky. Stacey was going into her junior year when Jeff Sheppard, a 6’3″ shooting guard from Marietta, Georgia, arrived on campus. She saw him for the first time while shooting around with her teammates at Memorial Coliseum.

“I saw him walk out onto the court. And I said to a teammate of mine, Kayla Campbell, ‘I’m gonna marry him one day.’ And she was like, ‘Girl, you’re crazy.’ And I was like, ‘Okay.’”

“I just remember her saying when she first met him, ‘I’m going to marry that boy one day,'” Fanning confirmed. “‘I’m going to marry him.’”

“I always liked [Jeff] because whenever Stacey saw him, she looked at me and said, ‘I’m going to marry him,'” Lola said.

Stacey kept an eye on Jeff over the coming months. Kentucky’s 1993-94 roster was loaded with stars — Walter McCarty, Tony Delk, Travis Ford, Rodrick Rhodes, and Rodney Dent just to name a few — which didn’t leave much playing time for a freshman. Add in a demanding coach like Rick Pitino and that’s a tough adjustment for a player who was Mr. Georgia Basketball.

“Jeff had been practicing and not playing a whole lot in the games,” Stacey said. “And I knew he was frustrated, and never really spoken to him. But I had read in the media guide that he enjoyed fishing.”

Knowing this was in her wheelhouse, Stacey decided to invite Sheppard to go fishing, crafting a “real simple letter” in study hall.

“I walked over and I gave it to him. Just laid it on the table and went back to sit down at my table. And I watched him read it. And then I watched him wad it up and throw it away. And I was like, ‘What a jerk.’”

“I think she may be misremembering this,” Jeff said, smiling. “I think she thought that I balled it up, and I actually just was strategically folding it in a certain way.”

Jeff finally wised up a year and a half later. One day, while she was in the training room icing her ankles, Jeff walked in and asked her to go with him to Ichthus, a Christian music festival in Wilmore.

“I always give him a hard time about it. There were so many red flags in the beginning, I should have just been like, ‘No, I’m out.’ But when he asked me to go to Ichthus, I was like, ‘Okay.’ I had no idea what it was. And I was like, ‘What do we need to wear?’ And he said, ‘Dress nice. It’ll be a nice event.’ Of course, it’s an outdoor concert in the middle of a field.”

When Stacey opened the door to greet Jeff that day, she was shocked to find him wearing sweatpants and a flannel jacket. She was dressed to the nines, wearing a velvet suit.

“‘I thought you said we had to dress up?'” she said. “And he was like, ‘Oh, I thought you knew I was joking.’ I got so mad. I was just like, really? It’s just another one of those stories, like I should have learned early that this is probably isn’t the right guy but I kept going back for more punishment.”

“I was clueless,” Jeff said. “And some would argue I’m still clueless. So she should have known from the start to leave me alone after I was so rude to ball up her very, very nice letter to me.”

From there, the two were smitten. Jeff came to Stacey’s games, where her family would surround him to make sure fans didn’t bother him too much. She stuck around Lexington after graduation in 1995, working for AmeriCorps and teaching and counseling at various schools while Jeff became a Kentucky Basketball star, winning the first of two national championships in 1996. In between basketball, they went fishing and frog-gigging at the pond on her parents’ farm. Jeff even rode his bicycle from Lexington to London once to see her, an hourlong trek by car. She ended up driving him back.

It was at that pond where Jeff proposed in the summer of 1997, although Stacey (unknowingly) tried her best to ruin it. The two had just gone out to eat and gotten back to the farm when Jeff asked her to stop at the pond instead of going up to her mom and dad’s house.

“I’m like, ‘Jeff, I’ve got good clothes on. I’m not stopping,’ and he was like, ‘Just stop at the pond.’ So he knew that my whole family was up at my house and already knew what was going on. So he knew if I went up there, somebody was gonna say something.”

“She was about to just destroy it,” Lola said.

“I did stop at the pond, eventually,” Stacey said.

Kentucky won the national championship again in 1998, with Jeff earning Final Four Most Valuable Player honors. He played briefly in the NBA with the Atlanta Hawks during the lockout season before getting an opportunity overseas with Benetton Treviso in Italy. He and Stacey moved to Treviso, where she tried out for a women’s professional team. The problem? Due to city regulations, they were only allowed one car.

“God works in mysterious ways,” Stacey said. “I was going to get a Ducati motorcycle so I could get back and forth to practice and stuff. And a week later, I found out I was pregnant with Madison. I didn’t get to play. I didn’t get my Ducati motorcycle. I just started getting fat.”

Stacey’s career as a player may have been over, but the next chapter of her story had only just begun.

“When they got married, I thought, well, now one of these days, there’s a chance to have a pretty athletic kid with some hops,” Fanning recalled. “You talk about Jeff’s athleticism because he’s a guy and he can get above the rim and all that. Stacey was a tremendous athlete and she had tremendous hops and quickness, but I think the demeanor part of [Reed] and the aggressiveness and the knack, that’s her.”

Madison Sheppard was born in July 2000. Reed followed in June 2004. By then, the Sheppards had settled back in London, where life returned to a version of Stacey’s as a child. Days were spent outdoors, fishing, hunting, or playing sports instead of inside playing video games. Madison and Reed were encouraged to try every sport or activity, with one caveat: they weren’t allowed to quit until after one full season. Madison played basketball and bucked the trend by trying dance. Reed tried everything: baseball, football, soccer, and basketball.

“We were never inside,” Reed said. “We were always doing something outside. Especially when I was younger, I was always wanting to do something, so I’d get on their nerves. We would throw football for 30 minutes. And I was like, ‘Alright, now let’s hit baseball. Now let’s hit the soccer ball and then shoot basketball.’ So it was always it was always something. I never wanted to sit in my room and play video games all day.”

Sometimes the activity would follow Reed from the outside in, much to Madison’s chagrin.

“The amount of times that he dribbled the ball inside of the house frustrated me to no end,” Madison said. “It was constant. I was like, ‘Reed, please go outside. There is a whole driveway for you to dribble.’”

It didn’t take long for Stacey and Jeff to realize Reed had something that a lot of other kids his age just didn’t.

“He kind of always had some natural tendencies athletically, even as a little bitty fella,” Jeff said. “He always showed incredible hand-eye coordination. You just throw him a ball and he’d catch it. So there was just phenomenal, God-given ability, because of his mama, that was inside of him.”

“I knew that early on he was very gifted naturally,” Stacey said. “And so I didn’t want to coddle him. Going back to, you do it the right way or don’t do it at all.”

Like her father, Stacey refused to take it easy on Reed and Madison, even when they were throwing the ball around the backyard.

“She never babied me in anything,” Reed said. “We would go out and throw football and she would throw it like she would throw it to me today…If it hit me in the face, it would hit me in the face. That was very important just because growing up, I had to get used to that.”

“She doesn’t try to pump your tires,” Lola said of her daughter. “With Reed, from any time that he’s played, she’s never allowed excuses. Whatever happened, it happened. ‘Son, you just have to put your big boy britches on and go on.’”

When Reed was four, Jeff started a travel team for him and his friends called The Sharks. Knowing that Reed had some natural gifts, Jeff purposefully scheduled games against older opponents to challenge him.

“My dad would put them in tournaments with people at least one or two years older than them so they never won,” Madison said. “Like, they just got beat to death. And he did it intentionally because he’s said, ‘You’re never gonna get better if you don’t play against anybody better than you.’”

“You just could tell he had it,” Jeff said of Reed. “He had something special.”

Despite all of that natural talent, Jeff and Stacey remained steadfast in their vow to let Madison and Reed choose their own paths. When they discussed having children, they agreed to not display any mementos from their careers at Kentucky so as to not put any pressure on them to follow in their footsteps.

“We said, look, we’re not hanging in any UK paraphernalia in the house,” Stacey said. “We’re not hanging in any pictures of anything that we did, that we’ve accomplished. We don’t want the kids growing up seeing that thinking that they’ve got to be this or that. They’re gonna make their own decisions.”

“If sports emerged as part of their passion and their talent, then great, and if it didn’t, then we would have been equally committed to pursuing whatever they wanted to pursue,” Jeff said. “We’re happy they picked basketball, for sure.”

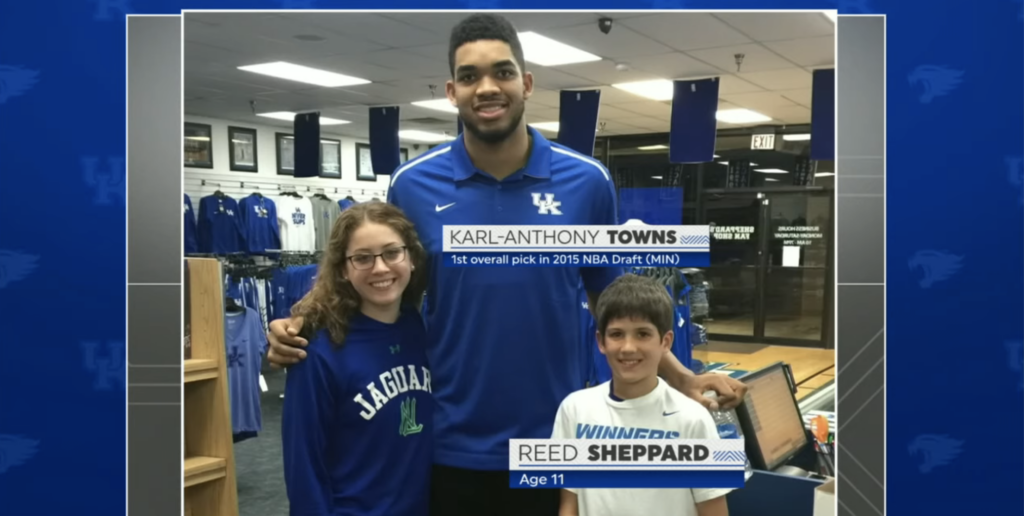

Reed’s interests narrowed as he got older. Instead of playing all the sports — baseball, soccer, football, basketball — he focused on baseball and basketball. By seventh grade, he decided he wanted to focus on just one sport. If you took one look at his childhood room, which was adorned with posters of Devin Booker, Karl-Anthony Towns, Anthony Davis, and John Wall, you’d know which won out.

“Once I did decide on just basketball, they were like, ‘Alright, we’ve got to do it now,'” Reed recalled.

Reed’s decision to commit to basketball meant the Sheppard family motto — give 100% in everything — extended not only to him but also to Stacey and Jeff as they helped him train and reach his potential. When a growth spurt hit, it became clear how much potential he had.

“Once he got to where we knew he was going to be 6’1”, 6’2”, 6’3”, we knew he was gonna have some good height as a basketball player,” Jeff said. “You started to know that he had a chance.”

“I knew he would play collegiately,” Madison said. “I didn’t know, at what level until about his seventh-grade year and I thought, okay, he’s pretty stinking good.”

Family pick-up games became even more competitive, to the point that one day, the result suddenly flipped.

“I’m like my dad,” Stacey said. “I would never let Reed win. If you’re going to score, you’re going to score because you scored on your own. Don’t bring that crap in here. You’ve got to handle the ball.”

“Anytime that we would play anything, whether it was me or mom or me and dad, I didn’t win,” Reed said. “I never won in a game until like seventh grade or eighth grade. That was finally when I could start beating them.”

“When we got to the point that he could beat us, we just quit playing,” Stacey said.

As Reed’s skills developed, you could see how much they resembled his parents’, specifically Stacey’s. Sharon Fanning got to see Reed play in person for the first time at an AAU Tournament in Birmingham in the summer of 2022. For her, it was like going back in time.

“When I watched him, the first thing that I thought was he looks a little more like Stacey playing than his dad. If you saw her run — you’d have to see her run. You’d have to know that bounce, that step. He did remind me a lot of some of the mannerisms of Stacey.”

“Reed is very good with his hands,” Stacey said. “And I was always very good with my hands. Just get your hands on balls.”

Hand-eye coordination is one thing, but the most important thing Stacey may have passed on to her son was instinct.

“Both of them play the game one play ahead and some of the things that a player has a knack for like that, you don’t teach,” Fanning said. “You either have it or you don’t have it. But I think he has the ‘It.’ The ‘it.’ Something that’s just inbred; it’s just a reaction. He plays the game one play ahead. He knows where the pass is before it happens. He anticipates, transitions right as it’s taking place.”

“In my mind, I was always going one or two plays ahead of where we were, like visualizing where somebody should be or what they should do, or how the defense was playing,” Stacey said. “Just always processing the game ahead of time. And Reed plays a lot like that.”

“A lot of people are trying their best to compare Reed to me,” Jeff said. “And they’re struggling because I wasn’t that good. And so they’re like, ‘Hey, he looks like him and he can dunk but we don’t remember him doing that. And we don’t remember him doing that either. And he’s actually good on defense, Jeff, you really weren’t good on defense. And he makes all his free throws.’

“And I said, Yeah, I know because you’re looking at the wrong parent. You gotta go over to Stacey to make the comparison.”

Dunks and threes may trick the untrained eye, but the real similarities in Stacey and Reed’s games show up on defense.

“Reed, his instincts and his feistiness – Shep was a laid-back but silent killer but Reed’s skill package is more like his mom’s,” Sean Woods said. “He’s more of a point guard and a straight two. Jeff was not a great break-you-down type of guy off the bounce, but she was. So he gets that from her. The point guard skills he gets from her.”

“They really are alike in a lot of ways,” Jeff said. “She was incredible with her hands on defense. She did it all. She rebounded, she passed the ball, she got steals, she tried to block shots at 5’7”. And you know what? That, if that sounds familiar, that’s why, because they’re a lot more alike on and off the basketball court and then Reed and I are.”

“I really do think I can see a combination of his parents,” Fanning said. “That should make him an even better player than both of them if he has both qualities.”

“Growing up, I’ve always heard that I’ve played like my mom,” Reed said. “And it’s really cool for me because it’s my mom. I’m a mama’s boy.”

As Reed’s star continued to rise, so did the chatter about whether or not he would fulfill the legacy fantasy by going to Kentucky. First, he had to prove he was good enough. Reed played for Indy Heat on the EYBL circuit and later, the Midwest Basketball Club on the Adidas 3SSB circuit, which meant long weekends on the road. With Jeff busy with his job as a financial advisor, Stacey would be the one to pack the car, head to wherever that weekend’s tournament, practices, or camp were, and keep an eye on Reed and his teammates. It was a sacrifice she was more than willing to make to ensure that Reed knew exactly what he needed to do to elevate his game.

“People would always say, ‘He’s the best.’ And I’m like, ‘No, he’s not.’ When we go play these tournaments, he’s good and he stands out, but he’s not the best. And so, taking him away to bigger tournaments and events, he was able to see it for himself and what he needed to do. And that drove him to want to be better.”

“He is a lot like her in the way that he’s just determined,” Madison said. “There have been many games where he didn’t necessarily love the way he performed. And so it’s 10 o’clock when we return home, and he’s going to the gym because he didn’t shoot well.”

“Her big thing was, just be yourself,” Reed said of his mother’s advice. “Never let anyone outwork you and never let anyone be tougher than you on the court.”

“She hated if you went out and didn’t try or didn’t play hard or pouted while you’re on the court. You’ve got to go out and no matter what, you’ve got to play as hard as you can. She didn’t care about missing shots or making shots. It was the way you competed.”

For Reed, those summers on the AAU circuit were just as important to his mental development as his physical development. After growing up in a town and state where everybody knew his name, travel ball provided both humility and motivation.

“Reed always had people that questioned him,” Stacey said. “Not his ability, but the opportunities that he was awarded because they were like, ‘He’s getting to go here, he’s getting to do that because of who his mom and dad are,’ and so he always had to fight against that.”

“So when he would get to the tournaments and he would play against better competition, for him, it was more mental. Like, ‘Do I belong here? Can I play with them?’ And then once the game started he’s like, ‘Yeah, I can compete and I’m just as good as they are.’”

Little did the Sheppard family know they were all about to get a crash course in toughness.

In late February 2021, Stacey was diagnosed with breast cancer. At the time, Reed was a sophomore in high school and Madison was a junior at Campbellsville University, a guard on the Tigers’ women’s basketball team. Stacey didn’t want to distract Madison with her diagnosis so she waited until after Campbellsville lost in the Mid-South Conference Tournament to tell her; even then, it was Madison who broached the topic, asking about her mother’s recent doctor’s appointments.

“She told me that they had found that it was breast cancer,” Madison said. “And I remember she said, ‘Madison, I want you to get your Bible out. And I want you to go to Deuteronomy 31:6. Be strong and courageous.’ And I remember her telling me, ‘You need to go read that verse. And I want you to read it out loud to me.’”

Top 10

- 1Hot

Stein Finds his QB

Kentucky Flips Kenny Minchey

- 2New

4-star flip!

'26 safety Andre Clarke to Kentucky

- 3New

Portal DB Addition

Florida's Aaron Gates to UK

- 4Trending

Transfer Portal Big Board

Where UK stands with top targets

- 5Breaking

8 Portal Commits

and a second OL.

Get the Daily On3 Newsletter in your inbox every morning

By clicking "Subscribe to Newsletter", I agree to On3's Privacy Notice, Terms, and use of my personal information described therein.

Stacey underwent a double mastectomy in April 2021. Madison stayed with her in the weeks and months after the surgery to help her recover while Jeff took Reed around on the AAU circuit. That time was not easy by any means, but Madison said her mother “handled it like a champ,” never complaining.

“That honestly opened my eyes to another layer of her,” Madison said. “I knew she was strong. I knew she was courageous but when you find something like that, it’s scary. And that also brought Reed and I together even more.”

“If she was anything on the court like she was during that journey, I would have been afraid of her. As a basketball player, I’d have been like, ‘Actually, can we switch? I’m not guarding her.'”

Reed, a self-professed mama’s boy, couldn’t hide his emotions while discussing his mother’s cancer battle.

“She’s the strongest person I know,” he whispered after a long pause, eyes shining.

With Stacey on the mend, the family turned its sights back to basketball. Schools started showing interest in Reed that spring. Kentucky was always in the back of everyone’s minds but it wasn’t until John Calipari and Orlando Antigua came to watch Reed play in person at North Laurel that the Sheppards knew their interest was real. Kentucky offered Reed a scholarship in July 2021.

“Once Kentucky got involved, again, for Reed, it was another affirmation that, I can do this,” Stacey said. “I belong there.”

Even with the legacy dream on the table, the Sheppards held their line, refusing to push Reed one way or another.

“A lot of people look at our family and think, well, every night they sit down, they watch film, and they break everything down, and we don’t,” Jeff said. “We really don’t. We truly just let the process play out how it was gonna play out. We wanted Reed to go through the recruitment process, and it to be his.”

That said, Madison made sure to get her concerns addressed during one of John Calipari’s in-home visits, which earned her a nickname from the Hall-of-Fame coach. After wrapping up his pitch, Calipari asked if anyone in the family had any questions for him. Madison, who was nearing the end of her own college basketball career, didn’t hesitate.

“How do you plan on investing in Reed after or outside of basketball so that when basketball is over, he can still be a person and know how to live and be a good man?”

“Coach Cal, he kind of laughed at me. And he was like, ‘Wow, you are his protector.’ And I was, first of all, like, ‘Why are you laughing? This isn’t funny. It’s not a joke.’”

By the fall, Reed had offers from several high-profile schools and had taken visits to Kentucky, Ohio State, Indiana, Louisville, and Virginia. The Cavaliers were thought to be the frontrunner, even by his parents, right up until the moment Reed sat them down to share his decision.

“We actually thought it was gonna be Virginia,” Stacey said. “But then he was like, ‘No, I want to go to Kentucky.’ And we’re like, ‘Okay, well, if that’s what you want to do, we don’t need to drag this out.’”

The Sheppards made a surprise visit to Lexington so Reed could tell Calipari the news in person.

“As a family, we’re making up all these stories to try to say, ‘Hey, we’re just gonna swing by and say hello, you know,’ but Reed wanted to do it face to face,” Jeff said. “I wanted him to do it face-to-face. I think that’s a decision that’s worthy of a face-to-face conversation.”

“We went by the office and Coach Cal was in there and he’s like, ‘What are y’all doing up here?” Stacey said.

“Reed’s nervously like, ‘Well, we wanted to come up here today because I wanted to tell you that I want to play basketball for Kentucky,’” Madison, who was secretly filming it all on her iPhone. “Coach Cal just shockingly looks around the room like, what? Are you serious? And he jumps up and gives Reed a hug.”

“That was really, really cool because I had Madison and mom and dad beside me while I was able to do that,” Reed said. “And they knew that it was my dream to play at Kentucky and mom and dad both playing at Kentucky and my sister, probably one of my biggest fans, if not my biggest fan, there beside me being able to do that with me and listen to me say that. And then Cal jumps up and gives us all a hug and just says that he’s super excited. It was a really really special moment for me.”

“It was an awesome, awesome moment,” Stacey said. “Reed was excited, Coach Cal and the staff were excited. He hollered at him, they all came in and hugs and tears – from us, not them – but it was a really neat experience. And for Reed to finally be able to say, ‘I’m going to Kentucky,’ and of course, he couldn’t announce it at that time, but to have that off of his mind and that weight off of his shoulders was pretty neat.”

A week later, Reed shared his decision with everyone else at a ceremony at North Laurel, the family all taking off North Laurel sweatshirts to reveal Kentucky gear.

The spotlight only got brighter on Reed once he committed to Kentucky. At times, it blinded him. In March 2022, Reed led North Laurel to its first Sweet 16 appearance in a decade. Unfortunately, his first game at Rupp Arena did not go as planned. Reed went just 5-20 from the field, finishing with 14 points, 8 rebounds, 6 steals, and 2 blocks in North Laurel’s first-round loss to Pikeville.

“The first year they got to the state tournament and he had one of the worst games that he could have possibly had,” Stacey said. “But the expectations he felt just smothered him. What people don’t know is during that time, he was a nervous wreck. He threw up two times before the game, he threw up at halftime, he felt the weight of the world on him and then he goes out and he lays an egg. It was bad. So he’s been through it.”

Reed’s struggles in the Sweet 16 only propelled him to work harder. After another strong summer on the Adidas circuit, he rose in the recruiting rankings and in January 2023, was named to the McDonald’s All-American Game, the ultimate honor for a high school basketball player. He was only the 15th player from the state of Kentucky to be selected for the game and the first since Chane Boehanan in 2011.

“The McDonald’s All-American Game was very important for him mentally, to know, ‘Hey, I do belong, I can play with these guys,'” Stacey said. “And after playing AAU against a lot of the top talent for two or three years, he knew he could, but just the affirmation of being selected to the McDonald’s Team.”

By the time Reed left for Houston in March, he had led North Laurel to its second consecutive 13th Region championship. Although the Jaguars once again lost in the opening round of the Sweet 16, this time to defending state champion George Rogers Clark, Reed turned in a much better performance, finishing with 23 points, seven assists, four rebounds, and four steals. A week later, he joined his future Kentucky teammates DJ Wagner, Aaron Bradshaw, and Justin Edwards at the McDonald’s All-American Game. He played the fewest minutes of any player there, totaling four points, four rebounds, three assists, and two steals; however, that wasn’t the point.

“When he got there, he’s said, ‘Mom, look, I might not even play, but I know I belong.’”

Just a few months later, Reed moved into his new home at UK. As the team prepared for the GLOBL Jam in Toronto, word spread that Reed was performing even better than expected in practice. That manifested into an impressive run during Kentucky’s four games in Canada, with Reed averaging 8.5 points and a team-high 5.75 assists per game.

Jeff, rocking a No. 15 Kentucky shirt, and Stacey were jubilant on the way to the arena for Reed’s unofficial debut in Canada, but both will tell you that once in their seats, they crumple into nerves. Stacey was so anxious ahead of Reed’s first official game at Rupp Arena on Nov. 6 that she didn’t eat all day and finally chowed down a hot dog right before tipoff. The camera tells no lies when it captures their reactions.

“We’re both pretty intense,” Jeff said. “We’re gonna use the word intense; we’re really just a mess and totally out of control is what we are. We’re a wreck.”

Madison said the family has a pregame ritual. As the team runs out of the tunnel for the first time, she and her husband will look to her parents one section over and flex. She also offered this tip to any fans sitting around the Sheppards during games.

“You don’t want to talk to him during that time. You don’t want to be like, ‘Mr. Sheppard, can I have your autograph?’ I promise you all, fans, that is not the time to do it. Please wait until after if you want a good encounter.”

Reed says he first started noticing how intense his parents were during games later in his high school years. Now, the whole world is getting to see dialed-in Stacey and Jeff. The two may have gotten more airtime on Tuesday’s ESPN broadcast than John Calipari.

“Seeing pictures and being able to see videos of them yelling and everything and cheering is really, really cool just because they haven’t changed,” Reed said. “Just because I’m at Kentucky now, on the highest level, they’re not cheering now like – they’ve been there when I was in second grade playing soccer and would get a goal.”

Over 30 years after playing Stacey one-on-one at Memorial Coliseum, Sean Woods now has a front-row seat to her son Reed’s development at Kentucky. The Unforgettable attends Kentucky’s practices regularly and one of his biggest takeaways thus far isn’t the five-star freshmen, returning sharpshooter Antonio Reeves, or invaluable transfer Tre Mitchell. It’s No. 15, already a favorite among former Kentucky Basketball players, not just because of his parents, but because of how he plays.

“He’s steady,” Woods said of Reed. “You can tell talented guys and you can tell guys who have been well coached. That’s what separates Reed from everybody else on the team right now, especially the young guys. You can tell he’s been taught the right way to play basketball, more so than these other guys.”

Woods has been the head coach at three different schools: Mississippi Valley State, Morehead State, and Southern. His experience and background as a Kentucky player, former head coach, and friend of Stacey and Jeff give him a unique perspective on Reed.

“He’s grown up in a house with two All-SEC performers, one was a Final Four MVP. You can’t do nothing than know more than most of those guys even though on paper, they’re more talented and more heralded. But I’ll take Reed Sheppards any day over anybody because of his know-how. He has a pace about him, a demeanor about him, a calmness, and that’s what separates him. He can’t be off the floor.”

Even in just a few months, Woods has seen Reed improve in practice. While he may not have the measurables that some of his five-star counterparts do, Woods said he’s learning and making up for it in other ways.

“He’s a ball thief. He just knows where the ball is. He has a knack for making good plays. And he’s becoming a better on-ball defender because that’s one thing I thought he was going to struggle with, was guarding the ball against quicker guys, but he’s learning now. His feet are getting quicker and he’s learning how to give a little bit to beat the guys to the spot and still take the ball.”

Case in point: at the end of Kentucky’s game vs. Saint Joseph’s on Nov. 20, cameras captured Reed embracing John Calipari. Reed did not score in the game but made two crucial steals in overtime to help the Cats seal the 96-88 victory. He also earned Calipari’s trust.

“He was just saying, ‘I’m proud of you, kid,'” Reed said of the moment with Calipari. “It was really cool because he took me out later in the second half because I made a few defensive errors and then he put me back in the end because he said he trusted me to go on and make the right play. And after I did that, that’s what he brought me over and he was like, ‘I’m proud of you kid.’ And after the game, he said, ‘That shows how much I trust you.’”

“He’s doing exactly what Cal wants him to do,” Woods said. “He’s not deviating from anything. He’s just using his God-given ability and what he’s learned as a basketball player.”

After Reed’s 21-point performance in Kentucky’s win over Miami on Nov. 28, Calipari recalled a recent conversation he had the night before with Chip Rupp, grandson of legendary Kentucky Basketball coach Adolph Rupp.

“He said, ‘Cal, did you think Reed would be this good? They’re talking about him being a knockdown shooter. He’s never been that. I watched him in 9th grade, 10th grade, 11th grade, 12th grade.'”

“You know what he has done?” Cal said. “He lives in that gym. He works. And he’s made himself kind of like Shai [Gilegous-Alexander] and some of these other kids that I have had. They build their own confidence. It’s not me saying you’re great or you are bad or…you know, it is them.”

You’d be hard-pressed to find a Kentucky fan who is unhappy with Reed Sheppard so far, but his family knows there will be bumps in the road. Stacey and Jeff know all too well the pressures that come with being a Kentucky Basketball player. Madison, Reed’s protector, worries about the toxicity of social media, even admitting that at one point during his recruitment, she wanted Reed to go to a different school in hopes of shielding him from the fan negativity. She’s already been reprimanded once by her little brother for going to war for him in the comments.

“Reed calls me and he’s like, ‘Hey, stop. Please do not comment to these people because number one, I don’t even see these comments most of the time. And all you’re doing is stirring them up.’ And so I was like, ‘Okay, humbled by my little brother.'”

When it comes to tuning out noise and bonding with his teammates, Reed has already taken a note from his mother’s playbook. In his first few weeks on campus during the summer, Reed invited some of his teammates to go fishing. Former Kentucky great and current UK Sports Network analyst Goose Givens accompanied the players on the trip to a local pond, where Reed taught his teammates the ins and outs of his favorite pastime.

“Me and mom go fishing a lot. Like, when we go on vacation, we go fishing. And so my teammates have never really been fishing and that’s one of my favorite things to do outside of basketball. Just to get away and do something new and be outside.”

“They had a lot of fun with it,” Reed said. “Most of the time, they never touched the fish until one of the last times we went, so I would have to run around the pond and go to them and help them take off the fish and then they would always talk a little smack to each other on who was the better fisherman. So it’s really, really cool being able to do that.”

Reed has another pillar of support, his longtime girlfriend Brailey. Stacey said Brailey “couldn’t care less about sports,” which is a blessing.

“For him, he has that getaway with her that, you know, they don’t have to discuss athletics, they don’t have to discuss anything. If he wants to talk about it, she’ll listen but it’s very important that you have somebody that you can just be yourself with and not discuss everything that you’re just engulfed with every single day. Those times to get away are pretty special.”

If you’re starting to think that Reed Sheppard is too good to be true, you’re not alone; Madison — always the protector — wouldn’t share any of Reed’s faults but joked about her brother’s taste in fashion (which he also inherited from his mother).

“He’s 19 years old. He’s a goofball. He wears camo Crocs after basketball games. And you’ve got all these teammates walking out with their chains and their fancy sweat suits, and he’s in his Crocs, and he doesn’t care. Like that’s who he is. And I’m so proud of him for that. Because I can imagine it’s really easy to give into a culture shift. And just your surroundings like to be influenced by that.”

“Reed doesn’t like the spotlight,” Stacey said. “Reed would prefer to be in the background. He’s not about the glitz and the glamour. He’s very quiet, very witty.”

“We like that Reed is just Reed,” Lola added. “He never thought that he is better than he is. He just realizes where his abilities have come from. He knows that he’s had to work hard to get to where he is. He has natural abilities, but he’s just worked to fine-tune all of them.”

There may be no better representation of Reed sticking to his roots than his haircut, the upside-down chili bowl that every boy has rocked at some point in his life. Reed fever is so intense in the Big Blue Nation right now that young fans are requesting the style at barber shops across the state.

“He’s just as he says, ‘I’m just a country boy from Eastern Kentucky,'” Lola said. “And he is.”

Stacey talks to her son at least once a day. After the Champions Classic, the two stayed on the phone for almost an hour as she drove back to London, dissecting Kentucky’s 89-84 loss to Kansas. The Sunday night before the game, Reed asked his parents to join him at the Joe Craft Center to help him work on his shot. Stacey was tasked with passing Reed the ball on the perimeter.

“I was trying to dribble in and emulate a game situation. Well, I was dribbling in and I kind of did a hesitation inside-out move and I threw the ball to Reed and he just busted out laughing. He couldn’t even shoot. He was like, ‘What are you doing?’ I said, ‘I’m trying to give you the best pass that I can, and to do that, I’ve got to make the right moves.'”

Her on-the-court instruction may not be what it once was, but Stacey is ready to cover the ground between London and Lexington at a moment’s notice if needed.

“Good, bad, or indifferent, if he needs to call we’re right there. And I said, ‘Look, anytime you need us, you know, I’m an hour away, I can be there in 45 minutes.'”

“She has really, really poured into him,” Lola said. “And she knew what it was like when she was in college. She knew it wasn’t for the faint of heart. And she tried to encourage him and instill that in him, that if he was going to exceed in anything that he has to work for it.”

Putting on a Kentucky Basketball jersey is an experience only a privileged few understand. For Stacey and Jeff, the only thing that can top it is watching their son do it every week.

“Just the pride of watching Kentucky and putting on that jersey,” Stacey said, recalling her days as a Wildcat. “Just that feeling of pride. It had nothing to do with my name on the back; it was all about the name on the front. Just living out a dream.”

“It was unbelievable,” Reed said of the first time he put on Kentucky blue and white. “It was definitely something I’ll never forget. It’s something I’ve always dreamed of. So being able to do that and run out in Rupp Arena in front of the fans for the first time was really, really cool.”

“For me to say it’s no big deal with him wearing a Kentucky jersey with the No. 15 on the front and Sheppard on the back is a lie,” Jeff admitted. “It’s very, very unique and it’s very, very cool and special to me, but it’s not as good as seeing the smile on his face and the joy that he’s playing with right now.”

If you’re curious, now that Reed is a Wildcat, Stacey and Jeff have started putting up some mementos from their time at Kentucky, but only alongside tributes to their children, and only after their daughter Madison’s wedding at their house this past summer.

“The groomsmen were all getting ready in the basement. I was like, you know what, I don’t want all this in the pictures and stuff, so we waited until after the wedding,” Stacey said. “We’ve got a whole wall section for Madison, a section for Reed, a section for Jeff, and a corner for me.”

Kentucky’s 22-point win over Miami on Tuesday was a statement for the program and a coming-out party for Reed, who played 30 minutes after starting point guard DJ Wagner went down with an injury. Once again, he led Kentucky in plus/minus efficiency at a staggering +35, enough to draw an eyebrow raise from his coach as he scanned the box score.

“His plus-minus was probably off the charts again,” Cal quipped. “Yeah, +35. So…”

At one point on Tuesday night, “Reed Sheppard” was the No. 2 trending topic on Twitter. Jay Bilas called him the most complete player on Kentucky’s roster. Dana O’Neil tabbed him as her early pick for freshman of the year. ESPN now projects him to be a first-round draft pick. In his postgame press conference, Cal once again made a point to credit Stacey for Reed’s instincts and feel for the game.

“I am not joking when I say this: that’s Stacey. That’s who that is. Jeff wasn’t that way. Stacey was that way. And, you know, you just see him get his hands on balls.”

The victory was also a cathartic moment for the Kentucky fanbase, which has endured several years of subpar basketball, a washed-out version of the Kentucky Basketball they knew and loved from the early Calipari years. On Tuesday night, the Cats were back in technicolor for all the world to see, right down to a raucous Rupp Arena. For a lifetime fan like Reed, it was especially sweet.

“The crowd was unbelievable. I don’t think they sat down. It was so loud. From the first possession to the last possession, they made a huge impact on the game. They made it tough for Miami to run plays. It will be a moment we will never forget.”

In the middle of it all were Stacey and Jeff, whose in-game nerves inevitably dissolve into pure joy, especially on nights like that.

“People have asked me often what it feels like to win a national championship,” Jeff said. “And I say it’s almost as good as seeing your kid score their first soccer goal or make their first layup or hit a shot at Rupp Arena. It’s almost that good. It’s not that good but it’s almost as good.”

“Reed’s gonna mess up, he’s gonna do stupid stuff, he’s gonna do great stuff and that’s part of the game,” Stacey said. “But just to watch him, and just to know it’s a confirmation for him and for us, what we’ve known the whole time, that he’s a special player. But to watch him do it on the biggest stage in college basketball is just — there are no words to describe that.”

Discuss This Article

Comments have moved.

Join the conversation and talk about this article and all things Kentucky Sports in the new KSR Message Board.

KSBoard