/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/58761115/180220_netflixthepush_news.0.jpg)

During the rise of Hitler’s Third Reich, a Jewish philosopher and political theorist named Hannah Arendt fled Germany for the United States. Following the war, she covered the trial of one of the holocaust’s main orchestrators, Adolf Eichmann. What she encountered in Eichmann was even more horrifying than she had expected. Eichmann was no monster. The one who organized genocide was just a normal guy like you and me, and the only thing scarier than a monster is the realization that we all have the potential to become the monster. This discovery is what led Arendt to coin the chilling but truthful phrase: The banality of evil.

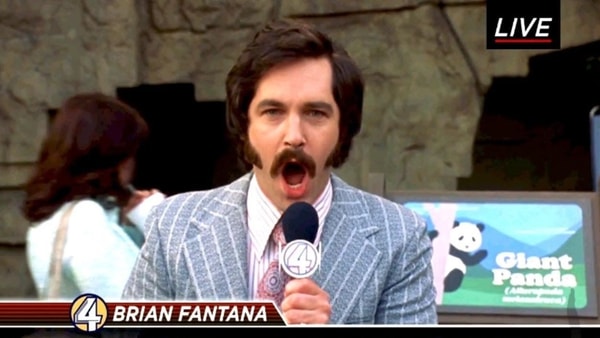

This past week, KSR, of all places, spent some time exploring the banality of evil. The conversation surrounded the Netflix special

The Push. Its premise is simple but controversial:

Can British sociologist/mentalist Darren Brown orchestrate an elaborate situation, performed by dozens of actors, to convince a normal unsuspecting person to commit murder? The audience follows a subject named Chris, as social pressure leads to one ethical compromise after another until he is so entangled in a web of deceit that the unthinkable becomes plausible. It seems the only way out is for Chris to ‘push’ someone (an actor that Chris does not know is strapped to a safety harness) off a roof.

Thankfully, Chris decides against it, but the viewer’s relief is quickly disrupted by the revelation that three others who went through the same experiment actually did it. Much of the debate on KSR regarded the show’s authenticity, but either way, the one thing history has taught is that the premise of

The Push is hauntingly authentic.

There is a word that conservatives love to deny and progressives love to use, but both seem to misunderstand: Systemic. It’s become a buzzword these days, but what does it actually mean? Simply put, it’s the idea that we all inhabit a world that, in some ways, functions like

The Push. Every culture is subject to powerful and elaborate structures that socially condition members of culture to think and behave a certain way. Therefore, it’s not as simple as good people making good choices and bad people making bad choices. The bad choices people make are borne out of a system that leads people ‘to push,’ so to speak.

Now if you are a conservative, then chances are you probably dismiss all systemic talk as liberal nonsense that only excuses individual responsibility. But I would argue that conservatives also believe in systemic ills. For example, what is meant by the axiom ‘fake news?’ The claim is that mainstream media is driven by a liberal agenda that determines both the news that is shared and the way it is shared. In other words, America’s mainstream news is ‘systemically’ shaped by progressive ideology. And the same can also be said about America’s public education and entertainment. So, for instance, if you ask a conservative how an issue like transgenderism goes from wholly implausible to aggressively normalized in the span of one generation, you will typically receive a systemic answer only without systemic verbiage—liberal media, education, entertainment, and so forth.

On the other hand, progressives have no problem acknowledging systemic power, but they tend to overestimate its power. That is to say, people are viewed as helpless victims of systemic injustice, and therefore culpability lies with the system, not the individuals making poor choices within the system. The true villain is not the participant that pushes, but rather Darren Brown and his team who orchestrated an oppressive social scenario that led to it. Without the system, they would never have done it, so it’s the system’s fault, not the individual. But this line of thinking is deeply problematic, not just ethically, but also practically.

For example, J.D. Vance wrote a memoir about life in Appalachian poverty called

Hillbilly Elegy, and progressives seemed to have a love/hate reaction to it. They loved it because Vance vividly portrays the destructive power of systemic poverty. There is no way to read his book and not be moved to deep sorrow and empathy for the seemingly helpless plight of the poor. But Vance is a conservative, and in the end, he concludes that, while we must have compassion on the victims of the system, ask how we ourselves are contributing to the system, and help in any way we can to fix the system, their unwillingness to take personal responsibility for their own poor choices is precisely what continues to perpetuate the problem. It is this “learned helplessness,” as Vance calls it, which continues the destructive cycle of Appalachian poverty.

So conservatives tend to deny systemic issues, and progressives tend to overplay systemic issues, which only begs the question: What are we to do with systemic issues? As a Christian minister, I believe the Bible offers a very compelling answer.

The doctrine of sin is something we don’t like to talk about, but it actually makes sense of this messy world we struggle to understand. It does away with the good people/bad people false dichotomy by indicting us all as bad people. We want to say the opposite is true, that we are all good people, but this fails to account for the profound evil in our world, not to mention the individual guilt and shame we all bear. It’s humbling to confess, but deep down we know it to be true: We are all deeply flawed individuals.

But the effects of sinfulness extend further than individual consequences. If it is true that we are all flawed, then everything we produce is likewise flawed. The cultures we create, the institutions we build, the systems we produce, all is tainted by the sinfulness of humanity. So you take a world filled with corrupt people creating corrupt structures which only perpetuate further corruption, and what do you get? The banality of evil.

It’s all very bleak and admittedly leaves us desperate for redemption (redemption that I believe is offered to the world in Jesus), but one has to admit that the doctrine of sin accounts for both the tragic power of systemic evil while retaining the necessary truth of individual responsibility. It explains why

The Push is so plausible while also indicting the one who actually pushes.

When Adolf Eichmann himself gave an account for the evils he committed, he tried to justify himself this way: “I was one of the many horses pulling the wagon and couldn't escape left or right because of the will of the driver.” I sympathize with Eichmann. I truly do. But the banality of evil is no excuse for evil. The will of the driver is indeed a powerful force, but it is not the responsible force. It’s Eichmann’s fault and Eichmann’s evil, because Eichmann chose to pull. Just as it’s our fault and our evil for the ways we choose to push.

Robert Cunningham is the Senior Pastor of Tates Creek Presbyterian Church. You can follow him on twitter at @tcpcrobert and send any comments/questions to [email protected]

[mobile_ad]

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/58761115/180220_netflixthepush_news.0.jpg) During the rise of Hitler’s Third Reich, a Jewish philosopher and political theorist named Hannah Arendt fled Germany for the United States. Following the war, she covered the trial of one of the holocaust’s main orchestrators, Adolf Eichmann. What she encountered in Eichmann was even more horrifying than she had expected. Eichmann was no monster. The one who organized genocide was just a normal guy like you and me, and the only thing scarier than a monster is the realization that we all have the potential to become the monster. This discovery is what led Arendt to coin the chilling but truthful phrase: The banality of evil.

This past week, KSR, of all places, spent some time exploring the banality of evil. The conversation surrounded the Netflix special The Push. Its premise is simple but controversial: Can British sociologist/mentalist Darren Brown orchestrate an elaborate situation, performed by dozens of actors, to convince a normal unsuspecting person to commit murder? The audience follows a subject named Chris, as social pressure leads to one ethical compromise after another until he is so entangled in a web of deceit that the unthinkable becomes plausible. It seems the only way out is for Chris to ‘push’ someone (an actor that Chris does not know is strapped to a safety harness) off a roof.

Thankfully, Chris decides against it, but the viewer’s relief is quickly disrupted by the revelation that three others who went through the same experiment actually did it. Much of the debate on KSR regarded the show’s authenticity, but either way, the one thing history has taught is that the premise of The Push is hauntingly authentic.

There is a word that conservatives love to deny and progressives love to use, but both seem to misunderstand: Systemic. It’s become a buzzword these days, but what does it actually mean? Simply put, it’s the idea that we all inhabit a world that, in some ways, functions like The Push. Every culture is subject to powerful and elaborate structures that socially condition members of culture to think and behave a certain way. Therefore, it’s not as simple as good people making good choices and bad people making bad choices. The bad choices people make are borne out of a system that leads people ‘to push,’ so to speak.

Now if you are a conservative, then chances are you probably dismiss all systemic talk as liberal nonsense that only excuses individual responsibility. But I would argue that conservatives also believe in systemic ills. For example, what is meant by the axiom ‘fake news?’ The claim is that mainstream media is driven by a liberal agenda that determines both the news that is shared and the way it is shared. In other words, America’s mainstream news is ‘systemically’ shaped by progressive ideology. And the same can also be said about America’s public education and entertainment. So, for instance, if you ask a conservative how an issue like transgenderism goes from wholly implausible to aggressively normalized in the span of one generation, you will typically receive a systemic answer only without systemic verbiage—liberal media, education, entertainment, and so forth.

On the other hand, progressives have no problem acknowledging systemic power, but they tend to overestimate its power. That is to say, people are viewed as helpless victims of systemic injustice, and therefore culpability lies with the system, not the individuals making poor choices within the system. The true villain is not the participant that pushes, but rather Darren Brown and his team who orchestrated an oppressive social scenario that led to it. Without the system, they would never have done it, so it’s the system’s fault, not the individual. But this line of thinking is deeply problematic, not just ethically, but also practically.

For example, J.D. Vance wrote a memoir about life in Appalachian poverty called Hillbilly Elegy, and progressives seemed to have a love/hate reaction to it. They loved it because Vance vividly portrays the destructive power of systemic poverty. There is no way to read his book and not be moved to deep sorrow and empathy for the seemingly helpless plight of the poor. But Vance is a conservative, and in the end, he concludes that, while we must have compassion on the victims of the system, ask how we ourselves are contributing to the system, and help in any way we can to fix the system, their unwillingness to take personal responsibility for their own poor choices is precisely what continues to perpetuate the problem. It is this “learned helplessness,” as Vance calls it, which continues the destructive cycle of Appalachian poverty.

So conservatives tend to deny systemic issues, and progressives tend to overplay systemic issues, which only begs the question: What are we to do with systemic issues? As a Christian minister, I believe the Bible offers a very compelling answer.

The doctrine of sin is something we don’t like to talk about, but it actually makes sense of this messy world we struggle to understand. It does away with the good people/bad people false dichotomy by indicting us all as bad people. We want to say the opposite is true, that we are all good people, but this fails to account for the profound evil in our world, not to mention the individual guilt and shame we all bear. It’s humbling to confess, but deep down we know it to be true: We are all deeply flawed individuals.

But the effects of sinfulness extend further than individual consequences. If it is true that we are all flawed, then everything we produce is likewise flawed. The cultures we create, the institutions we build, the systems we produce, all is tainted by the sinfulness of humanity. So you take a world filled with corrupt people creating corrupt structures which only perpetuate further corruption, and what do you get? The banality of evil.

It’s all very bleak and admittedly leaves us desperate for redemption (redemption that I believe is offered to the world in Jesus), but one has to admit that the doctrine of sin accounts for both the tragic power of systemic evil while retaining the necessary truth of individual responsibility. It explains why The Push is so plausible while also indicting the one who actually pushes.

When Adolf Eichmann himself gave an account for the evils he committed, he tried to justify himself this way: “I was one of the many horses pulling the wagon and couldn't escape left or right because of the will of the driver.” I sympathize with Eichmann. I truly do. But the banality of evil is no excuse for evil. The will of the driver is indeed a powerful force, but it is not the responsible force. It’s Eichmann’s fault and Eichmann’s evil, because Eichmann chose to pull. Just as it’s our fault and our evil for the ways we choose to push.

Robert Cunningham is the Senior Pastor of Tates Creek Presbyterian Church. You can follow him on twitter at @tcpcrobert and send any comments/questions to [email protected]

[mobile_ad]

During the rise of Hitler’s Third Reich, a Jewish philosopher and political theorist named Hannah Arendt fled Germany for the United States. Following the war, she covered the trial of one of the holocaust’s main orchestrators, Adolf Eichmann. What she encountered in Eichmann was even more horrifying than she had expected. Eichmann was no monster. The one who organized genocide was just a normal guy like you and me, and the only thing scarier than a monster is the realization that we all have the potential to become the monster. This discovery is what led Arendt to coin the chilling but truthful phrase: The banality of evil.

This past week, KSR, of all places, spent some time exploring the banality of evil. The conversation surrounded the Netflix special The Push. Its premise is simple but controversial: Can British sociologist/mentalist Darren Brown orchestrate an elaborate situation, performed by dozens of actors, to convince a normal unsuspecting person to commit murder? The audience follows a subject named Chris, as social pressure leads to one ethical compromise after another until he is so entangled in a web of deceit that the unthinkable becomes plausible. It seems the only way out is for Chris to ‘push’ someone (an actor that Chris does not know is strapped to a safety harness) off a roof.

Thankfully, Chris decides against it, but the viewer’s relief is quickly disrupted by the revelation that three others who went through the same experiment actually did it. Much of the debate on KSR regarded the show’s authenticity, but either way, the one thing history has taught is that the premise of The Push is hauntingly authentic.

There is a word that conservatives love to deny and progressives love to use, but both seem to misunderstand: Systemic. It’s become a buzzword these days, but what does it actually mean? Simply put, it’s the idea that we all inhabit a world that, in some ways, functions like The Push. Every culture is subject to powerful and elaborate structures that socially condition members of culture to think and behave a certain way. Therefore, it’s not as simple as good people making good choices and bad people making bad choices. The bad choices people make are borne out of a system that leads people ‘to push,’ so to speak.

Now if you are a conservative, then chances are you probably dismiss all systemic talk as liberal nonsense that only excuses individual responsibility. But I would argue that conservatives also believe in systemic ills. For example, what is meant by the axiom ‘fake news?’ The claim is that mainstream media is driven by a liberal agenda that determines both the news that is shared and the way it is shared. In other words, America’s mainstream news is ‘systemically’ shaped by progressive ideology. And the same can also be said about America’s public education and entertainment. So, for instance, if you ask a conservative how an issue like transgenderism goes from wholly implausible to aggressively normalized in the span of one generation, you will typically receive a systemic answer only without systemic verbiage—liberal media, education, entertainment, and so forth.

On the other hand, progressives have no problem acknowledging systemic power, but they tend to overestimate its power. That is to say, people are viewed as helpless victims of systemic injustice, and therefore culpability lies with the system, not the individuals making poor choices within the system. The true villain is not the participant that pushes, but rather Darren Brown and his team who orchestrated an oppressive social scenario that led to it. Without the system, they would never have done it, so it’s the system’s fault, not the individual. But this line of thinking is deeply problematic, not just ethically, but also practically.

For example, J.D. Vance wrote a memoir about life in Appalachian poverty called Hillbilly Elegy, and progressives seemed to have a love/hate reaction to it. They loved it because Vance vividly portrays the destructive power of systemic poverty. There is no way to read his book and not be moved to deep sorrow and empathy for the seemingly helpless plight of the poor. But Vance is a conservative, and in the end, he concludes that, while we must have compassion on the victims of the system, ask how we ourselves are contributing to the system, and help in any way we can to fix the system, their unwillingness to take personal responsibility for their own poor choices is precisely what continues to perpetuate the problem. It is this “learned helplessness,” as Vance calls it, which continues the destructive cycle of Appalachian poverty.

So conservatives tend to deny systemic issues, and progressives tend to overplay systemic issues, which only begs the question: What are we to do with systemic issues? As a Christian minister, I believe the Bible offers a very compelling answer.

The doctrine of sin is something we don’t like to talk about, but it actually makes sense of this messy world we struggle to understand. It does away with the good people/bad people false dichotomy by indicting us all as bad people. We want to say the opposite is true, that we are all good people, but this fails to account for the profound evil in our world, not to mention the individual guilt and shame we all bear. It’s humbling to confess, but deep down we know it to be true: We are all deeply flawed individuals.

But the effects of sinfulness extend further than individual consequences. If it is true that we are all flawed, then everything we produce is likewise flawed. The cultures we create, the institutions we build, the systems we produce, all is tainted by the sinfulness of humanity. So you take a world filled with corrupt people creating corrupt structures which only perpetuate further corruption, and what do you get? The banality of evil.

It’s all very bleak and admittedly leaves us desperate for redemption (redemption that I believe is offered to the world in Jesus), but one has to admit that the doctrine of sin accounts for both the tragic power of systemic evil while retaining the necessary truth of individual responsibility. It explains why The Push is so plausible while also indicting the one who actually pushes.

When Adolf Eichmann himself gave an account for the evils he committed, he tried to justify himself this way: “I was one of the many horses pulling the wagon and couldn't escape left or right because of the will of the driver.” I sympathize with Eichmann. I truly do. But the banality of evil is no excuse for evil. The will of the driver is indeed a powerful force, but it is not the responsible force. It’s Eichmann’s fault and Eichmann’s evil, because Eichmann chose to pull. Just as it’s our fault and our evil for the ways we choose to push.

Robert Cunningham is the Senior Pastor of Tates Creek Presbyterian Church. You can follow him on twitter at @tcpcrobert and send any comments/questions to [email protected]

[mobile_ad]

Discuss This Article

Comments have moved.

Join the conversation and talk about this article and all things Kentucky Sports in the new KSR Message Board.

KSBoard