Before there was Mahomes and Hurts, Michigan State's Willie Thrower blazed the trail

Another Super Bowl milestone of sports and society emerged from the NFC and AFC conference championship games when Philadelphia’s Jalen Hurts and Kansas City’s Patrick Mahomes advanced to Super Bowl XVII.

They will be the first two Black starting quarterbacks in a Super Bowl game when Sunday’s championship is kicked off.

And — as is often the case with Black athletes and milestones in college football and the NFL — history can be traced back to Michigan State’s ground-breaking teams of the 1950s and 1960s for the precursor for Sunday’s historic event.

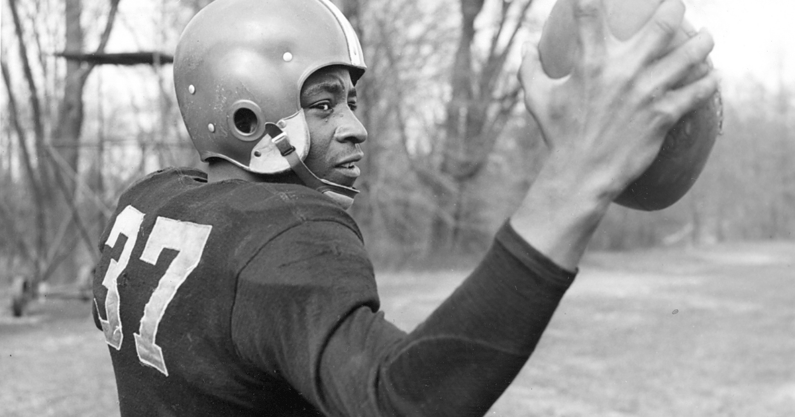

In 1953, Michigan State graduate Willie Thrower played for the Chicago Bears as the first Black quarterback in the NFL. Thrower, who was from New Kensington, Pa., played for the Spartans from 1950-52 as a backup to two All-American quarterbacks, Al Dorow (1951) and Tom Yewcic (1953). The Bears signed Thrower as an undrafted free agent and back-up to George Blanda, an eventual Pro Football Hall of Famer.

In 1965 and 1966, Michigan State’s Jimmy Raye of Fayetteville, N.C., was the South’s first Black quarterback to win a National Championship at the Division 1 level when he helped lead the Spartans to back-to-back shares of the national title.

Raye, recruited as part of coach Duffy Daugherty’s Underground Railroad of on-boarding top Black athletes from the South in the 1960s who were prevented from playing for major conference schools in the South in that era, also went on to a pioneering career as a college assistant and NFL assistant and offensive coordinator.

Thrower’s career at Michigan State gave Raye confidence that Daugherty would give him a fair chance to play quarterback. In the 1950s and 1960s, critics claimed that Black athletes weren’t capable of leading White players in a huddle. Daugherty smashed those stereotypes and many more while assembling college football’s first fully-integrated rosters.

The following details from Thrower’s career are excerpts from Chapter 5 of my book, “Raye of Light: Jimmy Raye, Duffy Daugherty, the Integration of College Football and the 1965-66 Michigan State Spartans.”

“Raye of Light,” published in 2014, was the first book to fully explain the significance and impact of Michigan State’s pioneering teams under Daugherty.

A display at the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio recognizes Thrower’s career and its social significance.

In the summer of 2022, Raye was honored among the inaugural recipients of the NFL’s “Awards of Excellence.” Raye was presented the award at the Pro Football Hall of Fame. The master of ceremonies was Pro Football Hall of Fame quarterback Dan Fouts, who praised Raye for his “perseverance.”

Thrower died in 2002.

NFL 360 produced a documentary on Raye’s career that aired on the NFL Network on Feb. 7. The NFL also held a special screening, with a panel discussion, on Wednesday at the Sidney Poitier New American Film School on the Arizona State campus in conjunction with Super Bowl Week.

THROWER’S JOURNEY TO MICHIGAN STATE

Thrower did not come to Michigan State from the South. Rather, he migrated to Michigan State from Pennsylvania, where the Spartans had had success mining talent of all backgrounds for Daugherty’s powerhouse.

Notable recruits from the Keystone State arrived when Daugherty was an assistant coach under Biggie Munn – players such as 1952 All-Americans Frank Kush of Windber, Pa., Dick Tamburo of New Kensington, Pa., and Yewcic of Conemaugh, Pa. became Spartans.

“It was a great venture for us at Michigan State,” said Thrower, of New Kensington, Pa, located outside of Pittsburgh. “We all enjoyed it.”

Thrower’s decision to attend Michigan State was based out of necessity and opportunity.

“Every college in the country wanted me – schools like Miami, Georgia, Kentucky – but as soon as they saw I was Black, that was end of it,” Thrower said. “So, I went north to Michigan State, where we had a fellow in front of me named Al Dorow, who later went to the Washington Redskins. Our stadium held 50,000 fans and they would chant, ‘We want Willie! We want Willie! ’”

Thrower, Tamburo and Vince Pisano were teammates at New Kensington as well as on Michigan State’s first officially sanctioned National Championship team in 1952.

Thrower did not receive recognition for his trailblazing accomplishments until many years later. His hometown was unaware he was the first Black quarterback in the NFL. Prior to the Civil Rights movement, the mainstream media avoided race in sports stories rather than report historic moments such as Thrower’s with the Bears. His pro debut was reported in Chicago papers as just that – his pro debut and not a ground-breaking moment for Black athletes at his position.

Chris Lamb is a Professor of Journalism at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis and has authored books on sports and race, including his 2004 work on Jackie Robinson breaking pro baseball’s color line: “Blackout, The Untold Story of Jackie Robinson’s First Spring Training.”

“Sportswriters wrote little about race and less about skin color of athletes for a number of reasons,” Lamb said. “Editors didn’t want their writers to write about race because it made readers and advertisers uncomfortable.”

Willie Thrower’s son, Willie Thrower Jr., said people in his hometown did not believe he was the NFL’s first black quarterback.

“It was only after he passed away that they started hearing the stories on TV,” Willie Jr. said. “Until then, people didn’t believe him, not even in his own hometown. That’s the saddest thing about it.”

Another son, Melvin Thrower, added, “My parents owned this bar called The Touchdown Lounge. My dad had a big picture of himself on the wall. On the bottom, it said, THE FIRST BLACK QUARTERBACK IN THE NFL, 1953.”

People told him to take it down. “You’re lying,” Melvin Thrower remembered them saying. “You’re lying. That ain’t you. Take it down.”

Hometown recognition finally came when he was elected to the Westmoreland County Hall of Fame in 1979. The Pro Football Hall of Fame righted wrongs when it honored Thrower as part of a 1988 display that recognized the NFL’s first Black players.

He passed away at age 71 in 2002, but a year later an official state marker was placed at his high school, now called Valley High. The school unveiled a statue of him at the football stadium entrance in 2006.

Also in 2006, Warren Moon, the first black quarterback inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame, mentioned Willie Thrower in his induction speech at the Canton, Ohio, museum.

Said Moon: “I also remember all the guys before me who blazed that trail to give me the inspiration and the motivation to keep going forward, like Willie Thrower, the first Black quarterback to play in an NFL game, like Marlin Briscoe, who is here today, the first to start in an NFL game. Like James Harris, who is here today, the first to lead his team to the playoffs.”

Thrower once told The Valley News Dispatch of Tarentum, Pa, “I look at it like this: I was the Jackie Robinson of football. A Black quarterback was unheard of before I hit the pros.”

During Thrower’s high school days, New Kensington High gained national attention when it won back-to-back Western Pennsylvania Interscholastic League (WPIAL) titles in 1946 and 1947. New Kensington was invited in 1947 to Miami to participate with other top teams from around the country in a football festival.

However, the organizers withdrew the invitation when they saw a photo of Thrower. Miami was a segregated city into the 1960s.

Thrower’s time at Michigan State overlapped a period All-American quarterbacks Dorow (1951) and Yewcic (1952) went on to play pro football. Dorow began in the NFL and later played in the Canadian Football League and American Football League through 1962. Yewcic, after a minor-league baseball career, played in the AFL with the Boston Patriots from 1961 to 1966.

In Michigan State’s 1952 season, Thrower completed 29 of 43 passes for 400 yards and five touchdowns in a backup role in a run-oriented offense as the Spartans went 9-0. Thrower’s numbers compare favorably to Yewcic’s All-American statistics as a starter: 41 of 95 passes for 941 yards and 10 touchdowns.

THROWER’S GREAT MOMENT AGAINST TEXAS A&M

Thrower counts as his biggest thrill Michigan State’s 48-6 win over Texas A&M in the 1952 season’s third game on Oct. 11 at Spartan Stadium (then called Macklin Stadium). Thrower entered the contest with four-and-a-half minutes to play and made it clear in the huddle what he planned.

“I said, ‘What we’re going to do is play pass and catch,” he said. “That’s all I’m going to do is throw the ball. I don’t care if it’s 2 yards for a first down. I’m going to throw it.”

Thrower was 7 of 9 for 107 yards and two touchdown passes. He captured the admiration of the Raymond George, the Texas A&M coach. George, who was Bear Bryant’s predecessor at Texas A&M, was ahead of his time as a coach who defied unwritten rules in the segregated South by scheduling his all-White teams to play integrated schools. A&M also played at UCLA in 1951.

“My greatest moment in football was playing against Texas A&M,” Thrower said. “I went in with four and a half minutes left and threw touchdown passes. After the game, the Texas A&M coach came to our locker room. He says, ‘Where’s this Willie Thrower guy?’ The players say, ‘Over there, No. 27.’

“We were the No. 1 team in the nation, and he comes over. ‘You know what?’ he says. ‘I was proud of my team today – until you stepped into the game. I’ll tell you what,’ he says. ‘If they don’t give you the game ball, you come to my locker room. I got one for you.’

“They didn’t give me the game ball and I didn’t go over and get one. I was just satisfied to get in there and play a little ball.”

George also said of Michigan State, “I’d say that on any given Saturday when the Spartans were at their peak – like this one — they’d likely beat any team, great ones of the past or present. It’s not so much the first team that hurts you, it’s (their) second and third that crush you.”

In the season’s eighth week, Thrower helped save the National Championship season against Notre Dame. Yewcic was injured with the Spartans clinging to a 7-3 lead in a home game. Thrower took the field and threw a touchdown pass en route to a 21-3 win. The victory extended the longest winning streak in the nation to 23 games. The streak ultimately reached 28, into the 1953 season. At the time, it was the ninth longest win streak in college football history, and the fourth longest of the 1900s.

Thrower helped wrap up the 1952 season in a one-sided season finale. He completed 7 of 11 passes for one touchdown and ran for a TD as the Spartans beat Marquette University, 62-13.

Top 10

- 1New

Fan who fell from stands

20-year old former CFB player

- 2

Kentucky, St. John's

Set to play in 2025-26

- 3Trending

Fan falls from stands

New update from Pirates game

- 4Hot

Bill Belichick

Netflix mocks coach, girlfriend

- 5

Bracketology

Way Too Early Tournament projection

Get the On3 Top 10 to your inbox every morning

By clicking "Subscribe to Newsletter", I agree to On3's Privacy Notice, Terms, and use of my personal information described therein.

“All in all, I’d like to be remembered as a great passer,” Thrower said. “I loved throwing the football.”

Being known as a passing quarterback in Thrower’s limited playing career served as an irony as Black quarterbacks slowly gained opportunities. As more Black quarterbacks played college football in the 1970s and 1980s, the knock against them in their NFL projections was they were running quarterbacks. But there was no mistaking Willie Thrower’s identity as a passer, especially in an era in which quarterbacks called many of their own plays.

“If we were ahead, they’d put him in and he’d call all pass plays,” Pisano said. “The whole student body would holler, ‘We want Willie!’”

Thrower’s arm strength took on mythic proportions. One day at practice, Michigan State’s kickers were having trouble booting into the stiff wind when the Spartans practiced kickoff coverage. Munn instructed Thrower to stand at the opposite 40-yard line and throw 60-yard tosses into the end zone to simulate kickoffs.

“We couldn’t practice kickoffs because of the wind,” Thrower said. “They said, ‘Willie get in there and throw that ball.’ I’d get back there on the 40 like a kickoff. I’d throw all the way to the end zone and they’d catch it and run back. I could throw it 80 yards. If you talked to people in New Ken, they’d say I could throw it 100 yards, but 80 yards was the most I ever threw it.”

Thrower moved on to his historic NFL season in 1953 when Chicago Bears coach and owner George Halas signed him as a free agent. Blanda was Thrower’s roommate.

Both quarterbacks were from western Pennsylvania, which later in the century gained fame as a cradle of quarterbacks. Blanda is joined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame with famous western Pennsylvania quarterbacks such as Johnny Unitas, Joe Namath, Joe Montana and Dan Marino.

In the Bears’ 1953 season, Thrower was suddenly a fan favorite in his pro debut on Oct. 18 against the San Francisco 49ers. Blanda was struggling and briefly hurt when Halas replaced him with Thrower. He completed a pass to put the Bears in scoring position, but he didn’t have a chance to finish the possession.

The Chicago Tribune wrote: “In the 10th minute of the period, (San Francisco’s Joe) Perry fumbled and (Chicago’s Dick) Hensley recovered on the 49ers’ 16. Willie Thrower, former Michigan State Negro quarterback star making his major league debut, passed 12 yards to (Jim) Dooley, putting the ball on the 4.”

The Tribune report continued, “Blanda and (Fred) Morrison came into the game with a resounding raspberry. They wanted Willie to put it over. But Morrison did it on a blast off tackle. The boos changed to cheers.”

Thrower only played in two games for the Bears, but he remembers a train trip from Chicago to face the Baltimore Colts.

“George told me, he said, ‘You know what Will? If I could throw a football like you, I’d play for the next 20 to 25 years. You can really throw that football.’ George really admired my passing.”

Oddly enough, Blanda played 26 pro seasons, but the end of his career was extended by his ability to kick the football. He served as a kicker and back-up quarterback during his Oakland Raiders days from 1967 to 1975.

The Bears released Thrower after the 1953 season, and he went on to play in the Canadian Football League. His career ended with a shoulder injury at age 27.

After Thrower, there was not another Black quarterback in pro football until 1968 in the American Football League and 1970 in the NFL. Marlin Briscoe (1968, AFL’s Denver Broncos) and James Harris (1969, AFL’s Buffalo Bills) started their careers in the AFL and they officially became part of the NFL with the 1970 merger.

Briscoe, though, was released by Denver after one year and converted to wide receiver once he was claimed by Buffalo in 1969. Harris remained a quarterback throughout his playing days with the Bills (1969-72), Los Angeles Rams (1973-76) and San Diego Chargers (1977-81). He was the first Black quarterback to start a playoff game with the Rams in 1974 and the first black quarterback named to the Pro Bowl in the same season.

After Thrower, the NFL’s early Black quarterbacks came from historically black schools or smaller colleges. Briscoe was from the University of Nebraska at Omaha and Harris from Grambling State University.

Raye was drafted in 1968 as a two-year starting quarterback out of Michigan State by the Los Angeles Rams in the 16th round, but he was converted to defensive back.

Grambling also produced Doug Williams as the first Black quarterback taken in the first round of NFL Draft when the Tampa Bay Buccaneers selected him in 1979 as the 17th pick overall.

Just one year before Williams was drafted, Warren Moon went undrafted after he led the University of Washington to a Pac-10 Conference title and Rose Bowl upset of Michigan. He played six years in the CFL before starting his NFL career with the Houston Oilers in 1984.

University of Houston quarterback Andre Ware won the Heisman Trophy in 1989 and Florida State University quarterback Charlie Ward did the same in 1993 as the first two black quarterbacks voted college football’s most prestigious award.

Ware was the seventh pick of the 1st Round by the Detroit Lions. Ward opted to play in the National Basketball Association with the New York Knicks when speculation mounted he would be a low draft pick in the NFL.

Other Black quarterbacks such as Second Round pick Randall Cunningham of the University of Nevada at Las Vegas and first-round pick Steve McNair of Alcorn State University enjoyed more success than Ware, but it was not until 1999 that a Black quarterback was a first-round pick out of a major conference school.

The 1999 NFL Draft was also a milestone with three black quarterbacks selected among the First Round’s top 11 picks. Philadelphia chose Syracuse University’s Donovan McNabb second overall, Cincinnati took the University of Oregon’s Akili Smith third overall and Minnesota tabbed Central Florida University’s Daunte Culpepper 11th overall.

The number of black quarterbacks starting at major colleges and in the NFL has changed dramatically in the 21st century. Quarterbacks who happen to be Black are no longer an exception. Auburn University alum Cam Newton of the Carolina Panthers and Baylor University alum Robert Griffin III of the Washington Redskins are called Heisman Trophy winners before they’re referred to as Black quarterbacks.

By the end of the 2012 NFL season, with Raye coaching in his 35th NFL season with Tampa Bay, NFL active rosters included six starting black quarterbacks and 16 overall. Tampa Bay’s 2012 season opener matched two starting quarterbacks who happened to be Black, Newton and Tampa Bay’s Josh Freeman.

American football is now in an era so far removed from 1966 when Raye was a pioneer Black quarterback that not even Raye realized the significance of what he was watching in the Carolina-Tampa Bay opener until it was pointed out to him later.

That moment, as well as the one the nation will witness this weekend on Super Bowl Sunday of 2023, can all be traced back to Michigan State’s Willie Thrower.

Tom Shanahan is a freelance writer based in Morrisville, N.C. He is the author of Raye of Light and won first place from the Football Writers Association of America for his 2022 story on the 1962 Rose Bowl and Segregation.

Purchase “Raye of Light” from August Publications at Tom Shanahan’s website: