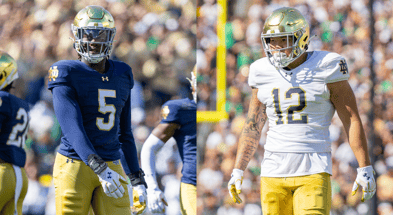

How Rico Flores Jr. avoided the streets of Sacramento to succeed at Notre Dame

This Notre Dame football article will appear in the next edition of Blue & Gold Illustrated the magazine. Start a subscription or order single copies by clicking here.

Rico Flores Jr. received the text in the early morning hours of a Saturday in February.

“Did you hear what happened to Cruz?”

He called the sender immediately. It was roughly 5 in the morning.

“That’s when they told me what happened,” Flores told Blue & Gold Illustrated. “I was just lost. I was shook after that. It still hurts.”

It’s been 19 months since Flores lost his childhood best friend, his “Godbrother,” to gang violence. The death is still an open case, so Flores didn’t expound upon how it happened. But it did, and the Notre Dame freshman wide receiver has been gutted ever since.

Cruz, two years older than Flores, was there the day Flores was born. Their mothers were good friends. Their fathers? Flores couldn’t accurately say. He’s never truly known his. His mom, Erin Floria, raised him in a single-parent household.

“He was in the streets too,” Flores said of his dad. “He was a dope boy. Turned out to be a drug addict.”

That’s commonplace in Flores’ hometown of North Highlands, Calif., just outside of Sacramento. Flores saw from an early age what dragged Cruz down and ultimately led to his loss of life.

“A whole lot of violence,” Flores said. “Drug abuse. Gangbanging. That was always around you. Hearing gunshots and helicopters at night. Seeing things that I shouldn’t have been seeing. That made me mature quick and fast.

“I was always curious about what was going on. I didn’t know what was good or bad. I just knew what it was. I saw everybody doing it around me, so that was the normal thing to do.”

Those are the words that keep every good-willed mother raising children in crime-ridden areas up at night. Erin knew her son was exposed to wrongdoings. But she couldn’t be so sure Flores knew the wrongdoings were, well, wrong.

So when Flores reached first grade, his mother deemed him old enough to take the first steps down a path that would one day lead him to one of the most prestigious academic and athletic institutions in the world — the University of Notre Dame.

It was going to be difficult. Time-consuming and expensive, perhaps more than she could afford on either front as a healthcare worker looking after adults with special needs.

But it was still going to be a heck of a lot easier than anybody ever having to wake up to a text that said, “Did you hear what happened to Rico?”

‘My Second Home’

Flores arrived at Lemuel Adams’ training facility, Game-Fit, as a curly-haired kid with clunky cleats that went well past his ankles. He thought he looked good, and he thought he played even better.

Adams thought otherwise.

“I’ll be the judge of that,” the former Washington State, Florida A&M and Arena Football League quarterback remembers telling Flores.

Flores ended up crying on day one. And two, and three, and so on. But he didn’t give up. His mother wouldn’t let him. Adams wouldn’t let him either. So Flores kept going to work, and he kept improving. Adams grew a liking to him rather quickly. There was just something about him.

“He’s a smart dude,” Adams said. “He’s fortunate to have his work ethic. He’s smart, man. Rico is a high football IQ dude. He’s able to apply the things he’s taught better than anyone else.”

Adams could tell Flores needed extra attention, intelligence aside. Flores’ mom was transparent with Adams; she told him about the situation at home and about how work would keep Flores out of her watchful eye more than she’d like.

Adams opened Game-Fit as early as 4 a.m. for Flores when he was still in elementary school. Flores went back after school for even more face time. Instead of gunshots and helicopters, Flores heard Xs and Os.

“I was there almost every day,” Flores said. “That was like my second home, the fit, just working there, grinding, seeing NFL and college players all in there working too. It showed me what I need to be.”

Flores closely monitored what it took for the likes of Terrance Mitchell, Robert Turbin, Arik Armstead and Taron Johnson, among others, to get to the NFL. They all worked with Adams at Game-Fit. Their presence made for a different world from the one at home, even if it was just right down the street.

Top 10

- 1New

Iowa State gambling

Staff members punished

- 2

Tennessee AD

Reacts to Texas roster cost

- 3Hot

2026 NFL Mock Draft

QBs dominate without Arch Manning

- 4

Second-guessing Sark?

Ewers-Manning decision in spotlight

- 5Trending

Fiery crash video

Alijah Arenas football surfaces

Get the On3 Top 10 to your inbox every morning

By clicking "Subscribe to Newsletter", I agree to On3's Privacy Notice, Terms, and use of my personal information described therein.

It shaped Flores’ view of adulthood for the better.

“I was still looking up to gang members and drug dealers and stuff before I got big into football,” Flores said. “That’s who had the money. That’s who was flashy.”

Number One

It’s Flores who’s flashy now. In a good way.

Through his first five college games, he has 11 receptions for 141 yards and a touchdown. The TD was a go-ahead score against then-No. 6 Ohio State in the fourth quarter of the most highly anticipated matchup of the first month of the college football season.

Flores added a 24-yard catch on an eventual game-winning drive at then-No. 17 Duke the following week. He tacked on a two-point conversion by way of a savvy slot relocation that left Notre Dame wide receivers coach Chansi Stuckey screaming, “Rico freaking Flores!” over the Fighting Irish coaching staff’s headset communication channel.

Flores’ coaches, past and present, aren’t surprised he’s produced in such a major way in the first few weeks of his college career. Folsom (Calif.) High School head coach Paul Doherty described Flores as “always on a mission.” Floria went out of her way to get Flores enrolled at Folsom, which is in a much better area than North Highlands, even though Flores never moved out of his childhood home 30 minutes away. That protected Flores from attending school in North Highlands.

“He made friends, but he made friends on the move,” Doherty said. “He had to go. He had to go to practice. He had to go to the weight room. He had to go to college. He had to go. He was getting out of here. You could go with him, but he wasn’t going to stop and hang around for any distractions — innocent or otherwise.

“He’s just a grown ass man out there playing football. That’s the way he carried himself and that’s the way he played.”

“He has no performance anxieties,” Notre Dame offensive coordinator Gerad Parker added. “He believes he has confidence in himself and he’s so eager to learn.”

That’s a credit to Flores’ mother as well as Adams, who she named her son’s Godfather not long after the two began bonding over training sessions — early in the morning and late at night.

Adams and Flores laid out a list of goals when he was old enough to dream of accomplishing them. Be a top youth prospect, check. Play varsity as a freshman, check. Twenty-five plus scholarship offers, check. He had well over 30. High School All-American, check. Play Division I snaps as a freshman, check. He’s scoring touchdowns at Notre Dame.

There are more boxes to fill between now and then, but the main objective is to be one of the first wide receivers taken in a future NFL Draft. The earlier, the better. Bonus money isn’t lost on Flores. He can make much more of it in a much more fulfilling manner than how it came to Cruz or his father.

When he gets it, he’s sharing it with his mother and 12-year-old sister. Moving them out of North Highlands. Erin Flores opened an avenue for her son to leave. It’d only be right if he returned the favor. That’s been his primary motivation for a while — to do for his family what Cruz can no longer do for his.

“Once I got that first offer, I realized this was my destiny,” Flores said.

And though he’s gone, Cruz is still very much a part of the journey. Just a few weeks before Cruz died, Flores posted an Instagram story asking what number he should wear in his senior season at Folsom.

“You’re always number one in my heart, brother,” Cruz responded. “I’m proud of you and I love you. Keep going.”

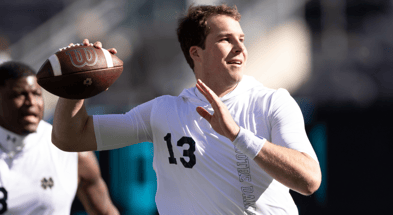

Flores is Notre Dame No. 17 as a freshman, but that likely won’t last.

“You’ll be seeing me in No. 1 soon enough.”