How Notre Dame LB Prince Kollie helped save the life of his high school coach

This Notre Dame football article will appear in the next magazine issue of Blue & Gold Illustrated. Sign up for a subscription or order a single issue here.

SOUTH BEND — Kevin Ramsey was on the field at FirstBank Stadium in Nashville when he received a text.

“Did you see? Are you there?”

“No, what happened?” Ramsey responded.

“He scored a touchdown.”

Ramsey’s heart crashed through the turf — in a good way. The best way.

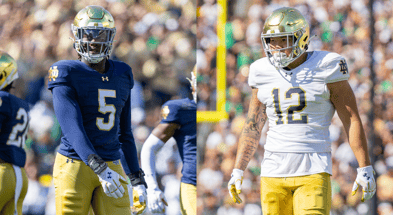

There was a time when he didn’t know if he’d ever see Notre Dame sophomore linebacker Prince Kollie, his protégé and a forever friend, enter the end zone in a college football game like he did to open the scoring in a 35-14 upset of then-No. 4 Clemson on Nov. 5.

There was a time when Ramsey didn’t know who he was. Or who Kollie was.

Or anything else about himself and the life he lived.

Ramsey, Kollie’s wide receivers coach at Jonesborough (Tenn.) David Crockett High School, fell ill with COVID-19 soon after the completion of Kollie’s senior season. He suffered from a serious bout with pneumonia. The illness prompted renal failure. Delirium set in.

“I almost died twice,” Ramsey told BlueandGold.com. “I spent about four days really only knowing my name.”

A 23-year Air Force veteran, Ramsey was isolated at the local Veterans Administration hospital for eight days in November 2020. Nobody was allowed to visit him as the public pushed through the pandemic. Ramsey was mentally incapacitated to the point of not remembering his iPhone passcode. The only time he spoke with family was when his wife called and he was able to press the answer button.

Those conversations were spent coaxing Ramsey back into his right state of mind. Ramsey had helpers in doing so on his wrist, too; one black wristband with the word “REMEMBER” in big, bold, white lettering and another white one with a gold, interlocking Notre Dame logo.

Kollie committed to the Fighting Irish three months prior. Ramsey was his right-hand man in getting him to that point. The two share a bond rooted in recruiting road trips that spawned eight-hour conversations about adversity, leadership, life goals and, of course, football. The sport was the reason Ramsey wore the Notre Dame wristband, after all.

But he wouldn’t have donned it if Kollie did not mean the world to him.

Every time Ramsey’s wife hung up the phone, Kollie was on her call list. Kollie made sure of it. He relayed what she told him to his teammates at David Crockett. He orchestrated prayer vigils. He disseminated updates to then-Notre Dame defensive coordinator Clark Lea and graduate assistant Nick Lezynski, who Ramsey formed relationships with while the Irish pursued Kollie as a prospect.

Lezynski lit a candle at the Grotto of Our Lady of Lourdes every day while Ramsey was in the hospital. The more Ramsey stared at his Notre Dame wristband, the more it all came back to him. He had people who loved him. People praying for him to make it through, Kollie as instrumental as Ramsey’s kin, chieftains of the crusade.

Kollie said if it wasn’t for Ramsey’s support, he wouldn’t have enrolled at a prestigious program like Notre Dame. Standing by Ramsey’s bedside in spirit was a form of reciprocation.

“He’s done so much for me that it was only right,” Kollie told BlueandGold.com. “I felt obligated to do what I can, say my prayers and be there for him and his family. That was a tough time for him. I felt like it was my duty, so that’s what I did.”

There’s a sense of power in persistent purpose that always seems to overcome even the toughest of odds. Ramsey eventually came into his own.

“The more I was able to remember about Prince and his recruitment and all the trips we went on helped to bring me out of it,” Ramsey said. “My family, Prince, a lot of players I coached and a Fender guitar probably saved my life.”

Selfless Nature

The guitar is a vehicle of therapy.

Deployments to Iraq, Afghanistan, Kuwait, Qatar and various other overseas outposts after Sept. 11, 2001, and everything that went into more than two decades of military service caught up to Ramsey after his recovery from COVID.

Delirium didn’t hold him hostage anymore. Depression did.

StopSoldierSuicide.org reports veterans are at 57% higher risk of suicide than those who haven’t served. There were 6,146 veteran suicides in 2020, the same year Ramsey’s life took a turn. Military suicide deaths are projected to be 23-times higher than the number of post-9/11 combat deaths by 2030.

Ramsey is aware of the numbers. He’s saddened by them. He labors to reverse them.

He formed the Tennessee chapter of Music For Veterans in January of this year. A nonprofit whose slogan is “peace through music,” the organization provides safe spaces for veterans to socialize and heal through playing instruments and relishing in the sounds of them.

That Fender guitar has dug Ramsey out of some “dark holes”

“If you have a nightmare at 3 o’clock in the morning, it’s hard to get to a therapist,” Ramsey said. “But if you can pick up a guitar and that can ease your anxiety for that morning and get you back to sleep, that hopefully will make a difference in whatever you’re dealing with.”

Kollie is mindful of those sorts of struggles. His head coach, Hayden Chandley, and linebackers coach, Ron Sillman, at David Crockett are military veterans. Two of his best friends, Mark Seidler and Gage Skalecki, are currently in the armed forces.

Seidler is at the U.S. Army post in Fort Carson, Colorado. He ships off to Korea for a nine-month deployment in June of next year. Skalecki is with the U.S. Marine Corps. He was on duty in Kabul when the U.S. turbulently evacuated its troops from Afghanistan last year. Kollie said he “didn’t know how to operate” when he couldn’t communicate consistently with Seidler in basic training and Skalecki in deployment.

“He knows what sacrifice looks like,” Seidler told BlueandGold.com. “It holds a spot in his heart because he’s a real personal guy and a caring guy for the ones that he’s close to. He’s always making sure the ones around him are good.”

Kollie donates a part of his profits from his name, image and likeness (NIL) proceeds to Music For Veterans. He shares social media posts supporting the cause. His family immigrated to America to flee the Second Liberian Civil War when he was a toddler.

Top 10

- 1New

Donald Trump blasts NFL

Teams for not drafting Sheduer Sanders

- 2

Jaden Rashada

Makes transfer commitment

- 3

Kim Mulkey

Takes victory lap on South Carolina

- 4Hot

2nd Round NFL Mock Draft

QBs under microscope

- 5

Shedeur Sanders reacts

To going undrafted in 1st round

Get the On3 Top 10 to your inbox every morning

By clicking "Subscribe to Newsletter", I agree to On3's Privacy Notice, Terms, and use of my personal information described therein.

If anyone knows what it means to say freedom isn’t free, it’s Kollie.

“They’ve done a lot for our country,” Kollie said of veterans. “They’re really selfless. Kevin Ramsey and my friends embody that. They’re selfless guys, always putting others first. I’m drawn to that. That’s how I try to be; selfless. I’m just really appreciative of our military and what they’ve done.”

Being Better

Ramsey had a good reason for not being at the Notre Dame game when Kollie scored the touchdown vs. Clemson. He was a special guest of Lea’s and Lezynski’s at Vanderbilt’s military appreciation game vs. South Carolina.

When Kollie plucked the ball out of midair off a blocked punt and sprinted 17 yards past the pylon, Seidler was over 1,100 miles west of where Ramsey shed prideful tears on Vandy’s field.

“When that happened, I was literally screaming in the barracks,” Seidler said. “Chills up my body like, ‘Wow. He’s really doing that.’”

“It was like old times seeing you carry the rock into the end zone,” Ramsey said he told Kollie.

Seidler, two years Kollie’s senior, also played linebacker at David Crockett. They’ve been friends since middle school. Seidler suited up for one season at Texas Wesleyan, but he wasn’t on a full scholarship. The pandemic hit hard, and student loans did too. He enlisted in the Army with intent to return to play collegiately in 2024 or 2025 without worrying about tuition.

It was always the duo’s dream to play college ball. When Kollie excelled as a 1,000-yard running back and a 1,000-yard receiver in addition to being a menace on defense and special teams, he took a town of just under 6,000 residents by storm.

The big offers didn’t go Seidler’s way. But if he wasn’t going to get them, it was no small consolation for them to go to his best friend.

“Everybody in Jonesborough knows him,” Seidler said. “So seeing him on the stage he’s on now, making plays vs. top-ranked teams, I literally get chills watching it because there is nobody more deserving. This is what we talked about years and years in advance.”

Ramsey went to six games during Kollie’s freshman season at Notre Dame. He went to four of the first nine this year despite numerous weekend obligations with Music For Veterans. When Kollie had a minor case of COVID in September of 2021 and missed two games, Ramsey FaceTimed him so the two could watch the Irish together hundreds of miles apart. He sympathized with the loneliness.

Seidler watched eight of Kollie’s first nine games this season from his barracks in Fort Carson. He was in the training field for the one he missed.

There are authentic connections behind such devoted acts of support. But that’s a two-way street. Kollie has always been there for Ramsey and Seidler. So they’re always going to be there for him. They don’t have to be in South Bend, Ind., to show that. They can do it from Tennessee, Colorado and even Korea.

It won’t always be about a 60-minute game played under the lights on Saturdays, either. It’ll be about deep conversations when the car is in cruise control. It’ll be about lighting candles at the Grotto and phone calls with loved ones in times of need.

It’ll be about a middle-aged man retiring from MacDill Air Force Base as a Lieutenant Colonel in Tampa, Fla., after 23 years of service relocating to his native Tennessee, meeting, coaching and befriending a young man whose family fled to the U.S. to avoid a violent overseas civil war.

It’ll be about Fender guitars.

“There are better things in this life than football,” Kollie said. “The game will end for everybody at some point. I’m always looking past it to see how I can be better.”