How someone Aneyas Williams won’t ever get back but won’t ever forget drives the Notre Dame freshman running back

Aneyas Williams doesn’t wear his emotions on his sleeve. He’s rather stoic, a slick smile signifying his every mood. The Notre Dame freshman running back wears a tattoo under his sleeve, though, serving as a reminder of who he should and shouldn’t be.

It’s a newspaper-script font “W” with barbed wire branching out from either side, connecting his bicep to his triceps, connecting him to a father he hasn’t known for over eight years.

Williams’ dad, Lydell Williams, died of a heart issue brought on by substance abuse in Sept. 2016. He was 38. Aneyas was 10. A sixth-grader.

A pallbearer.

Lydell, barbed wire and a big “W” covering his own arm, went to Georgia to get his life on track in his mid 30s. He never returned. He wasn’t around his son much for his final four years.

The memory of him, his accomplishments, who he was before his demise? That never left.

Aneyas knew just who his dad was, and, in a sense, he was exactly who Aneyas wanted to be — one of the best football and track stars to ever attend Hannibal (Mo.) High School.

“Hannibal is 100 percent a football town,” Hannibal head coach Jeff Gschwender told Blue & Gold Illustrated. “And when one of your legends dies, it’s a pretty big deal around here. I’m sure that did affect Aneyas quite a bit.”

It did. It drove him.

“After dad passed, I feel his drive for his dreams grew even bigger,” Aneyas’ sister, Alivia Williams, told Blue & Gold.

Soon into his freshman year, Aneyas realized he had what it took — the innate athleticism and undying determination to match — to eventually become a legend of his own.

But that’s when the boy who hardly displayed his feelings, the boy who scored four touchdowns in his first varsity game, let his guard down.

And let it all out.

After his awe-inspiring debut performance, Aneyas gave his mother, Sarah Williams, a huge hug, in front of everybody, tears flooding down his face for all to see — if he could ever lift his head off his mom’s shoulder.

He couldn’t. Didn’t want to. Why would he?

“When he broke down on that field I think it was kind of like, ‘Man, this sucks. I’m happy, I want to share this with my mom, but I also want to share this with my dad. There is a part of me that’s missing,’” Sarah told Blue & Gold. “I think that kind of followed him here to Notre Dame.

“Each accomplishment. Each offer. Decision day. His first touchdown. There is a certain part of him — he’s proud, he’s happy — but there is a certain part of him that’s missing.”

‘That Kid’

Lydell played at Southern Missouri University. His talent was always going to take him to the next level. Aneyas? More than talent.

His everything was always going to take him to the next level.

“Every single year you have kids, I don’t care what game, what sport you coach, but especially football, where it’s like, ‘My goodness, man, if this kid’s body had this kid’s brain, he’d be a heck of a player,” Gschwender said. “’If this kid’s brain had this kid’s body, could you imagine?’ Aneyas was that kid that had the brain and the body that was, like, ‘This is that kid, this is that combination that every coach is always looking for.’”

Aneyas has a unique knack for taking a coaching cue, Gschwender said, and enacting it immediately, like it’s the coach himself conducting an instructional rep. Only it’s the real thing, full speed, defensive players in hot pursuit, and Aneyas pulls off exactly what’s being asked of him.

Gschwender recalled sitting in his office late on Friday nights — er, early on Saturday mornings — reviewing film from the game played hours earlier. He’d text Aneyas pointers as simple as “hit your landmark better next time.”

Monday morning? Landmark met.

“That’s something that may not seem like a whole lot, but boy, when you’ve been coaching for a while, that’s a big deal,” Gschwender said.

Blowing Up

Aneyas wasn’t just a superstar in the making in the Missouri high school ranks. He became mainstream nationally after his appearance at the All-American Bowl combine in San Antonio between his sophomore and junior seasons at Hannibal.

Dwayne Carter, a trainer whose brother, Michael Carter, scored 7 touchdowns as an NFL running back with the New York Jets over two seasons in 2021 and 2022, saw a kid in all white with pink cleats, pink gloves and a pink headband at the combine and instantly gravitated to him. Carter had been around pros in his brother and Jacksonville Jaguars defensive tackle Jordan Jefferson, among others. He knew the way they carried themselves. He instantly saw it in Aneyas.

Carter keyed in on him for a few drills, during which Aneyas ran “crispy” Texas routes and stick nods, and logged him at a 4.46-second 40-yard dash. His conclusion was pretty clearcut.

“This is one of the best high school kids I’ve really ever seen, and I’ve seen some guys,” Carter told Blue & Gold.

That was especially evident after Carter got Aneyas down to his training center in Florida and let him take part in a 7 on 7 tournament in one of the most talent-rich high school football states in the country. Aneyas outshined Raymond Cottrell and Vicari Swain, the former a former Texas A&M wide receiver and the latter a South Carolina sophomore defensive back.

The kid from the sleepy SEC state was no longer slept on.

“He came out there and was our best player,” Carter said. “It kind of woke people up, like, ‘OK, this is not a Missouri thing.’ This kid is good.”

Carter contacted Dre Brown of Notre Dame and Robert Gillespie of Alabama. Both premier programs offered Aneyas a scholarship. Just like that, he had the power to go pretty much anywhere he wanted.

Top 10

- 1New

Donald Trump blasts NFL

Teams for not drafting Sheduer Sanders

- 2

Jaden Rashada

Makes transfer commitment

- 3

Kim Mulkey

Takes victory lap on South Carolina

- 4Hot

2nd Round NFL Mock Draft

QBs under microscope

- 5

Shedeur Sanders reacts

To going undrafted in 1st round

Get the On3 Top 10 to your inbox every morning

By clicking "Subscribe to Newsletter", I agree to On3's Privacy Notice, Terms, and use of my personal information described therein.

“You know what happens after Notre Dame and a school like that come through,” Carter said. “It kind of blew up from there.”

‘Earning That Trust’

It was a strong bond Aneyas formed with Notre Dame running backs coach Deland McCullough that sold him on South Bend as his collegiate destination. Gschwender spoke of many encounters with McCullough in Hannibal.

“I know Aneyas has the highest respect for him,” Gschwender said, “and there is not a better guy to get locked into than him.”

Getting to work with a players’ coach like Marcus Freeman and an offensive coordinator with as much wisdom as Mike Denbrock? Added bonuses.

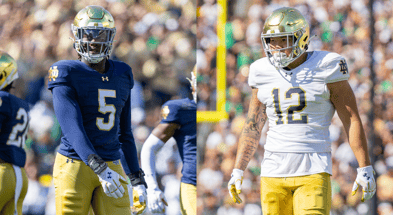

Both have Aneyas’ back and empowered him to run for 112 yards and a touchdown on 23 carries and catch 7 passes for 86 yards in his first 10 career games in a backfield with soon-to-be NFL Draft picks Jeremiyah Love and Jadarian Price on the depth chart ahead of him.

Freeman said Aneyas expedited the learning curve of a typical freshman with a relentless work ethic.

“He was doing a good job early in the season, as a freshman, of getting his job done without the ball in his hands,” Freeman said. “Now he’s doing some things with the ball in his hands that are impacting our offense.”

“What he’s gotten, he’s earned,” Denbrock added. “And rightfully so.”

Earning it is exactly what Aneyas astutely knew he needed to do as a freshman in a position group with a graduate senior, a junior, two sophomores and a fellow freshman.

“Earning that trust and respect from the coaches just gives you humility and confidence you need to go out there and do your job,” Aneyas said. “That’s what I’ve been focusing on.”

‘All They Talk About’

His father’s death is a source of humility, too. Aneyas knows everything he’s ever worked for can be snatched from him in an instant if he doesn’t continue down the right path.

Every game day in Hannibal, even if it was a Midwestern blizzard, Aneyas went to his father’s gravesite and prayed. He’s got a tattoo on his right quadriceps with one hand reaching out to another, two dates in the form of Roman numerals listed beneath them. The first, the day his father was born. The second, the day he died.

It’s a reminder every time he slips on his gold Notre Dame football pants — an identical reminder to the one he got when he stared at the same dates on Lydell’s tombstone game day after game day.

Don’t take anything for granted. Play every game like it’s your last.

“His outlet is football,” Sarah Williams said. “I think that’s where he grew and learned and dealt with a lot of stuff. He internalized it and put it out there on the field.”

Aneyas has a tattoo on his wrist that spells out “IKAIGI” — a Japanese word that refers to a reason for being. That one is not for his father.

It’s for his mother. And it’s also a reminder.

Aneyas is never going to get his dad back, but he’s always going to have his mom. His sisters. The folks back in Hannibal who clamor about his accomplishments to Sarah at Walmart. The ones who hold watch parties at the town of roughly 17,000’s finest watering holes.

“He’s all they talk about,” Sarah said.

Family, friends. Teammates, coaches. Aneyas has support from everyone who’s ever helped him get to where he is now — at the very beginning of a promising collegiate career at Notre Dame and whatever’s after that.

“I just pray that he utilizes this opportunity to do and be everything that he can be,” Sarah said. “He’s definitely got potential to go very far. Keep him healthy, keep a level head on his shoulders. He’ll do everything he needs to do to get there.”