‘When you hit rock bottom’: Inside Riley Leonard’s season-long odyssey at Notre Dame

In hindsight, Riley Leonard wishes he knew what was in that box.

During the early weeks of his season as the starting quarterback at Notre Dame, fans would send mail and the occasional package to his house. The most memorable one said “grandma’s cookies” on it, for some reason. Leonard didn’t care to find out what was inside.

“It’s like, ‘Alright, what’s in this box?’” Leonard told Blue & Gold, laughing. “I wish I would’ve opened it now.”

Leonard, now a sixth-round pick of the Indianapolis Colts, could look back and laugh during a Zoom interview April 12. It wasn’t as easy at the time. It was September, and Leonard was deeply unpopular.

He was the prized transfer quarterback whose performance against Northern Illinois led to one of the most embarrassing losses in program history. Some of the criticism he could avoid. Others, he didn’t have a choice. Boxes weren’t the worst of it.

After one of the most remarkable single-season journeys a quarterback can have, though, they are among his few regrets.

“At the time, I would get those boxes and just throw them away immediately,” Leonard said. “But now, looking back, I’m like, ‘What was really in those boxes?’”

Leonard sat in the locker room at Ross-Ade Stadium in West Lafayette, his life as a quarterback flashing before his eyes.

He had convinced himself that Purdue, who would not win another game the rest of the season, was the best team in the country. Maybe even the world. He had no choice but to treat that game like the Super Bowl.

“It’s easily the most nervous I’ve been before any game of all time,” Leonard said.

That week began, as Leonard has told other outlets, with a meeting in Notre Dame head coach Marcus Freeman’s office. As the story goes, he thought Freeman was about to tell him he would never start for the Irish again. Instead, his coach laughed and told him that one day, he’d be thankful for NIU.

But while Freeman might not have told him explicitly, Leonard knew his performance at Purdue would dictate what happened next.

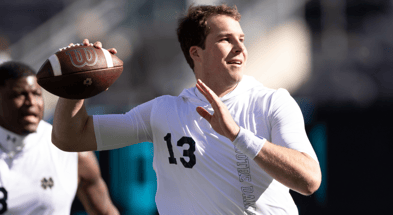

Of course, Leonard played well. He wasn’t perfect, but he ran for 3 touchdowns, built a 42-0 first-half lead as the Boilermakers capitulated and did more than enough to keep his job.

It also reassured him that the Irish were who they thought they were.

“After that game, even, it was like, ‘Alright, we know who we are,’” Leonard said.

“‘Week 2 was a fluke. It was the best thing that could’ve happened to us. We know we can beat anybody in the country if we play like this.’”

But there was still a lingering feeling, Leonard explained, that Notre Dame might never get to prove it. The Irish knew one more loss would eliminate them from playoff contention. And thus began their 81-day odyssey of “survive and advance.”

Leonard would later write in a Players’ Tribune article that Notre Dame took the “hardest, messiest, craziest path by far” to the CFP. He told BGI that it was a weird feeling each week, not being able to celebrate wins. He and his teammates knew that if they didn’t do the same next week, they would be done.

“Yeah, shoot, every week was a dogfight,” Leonard said. “It was catching up all season. We were never ahead of schedule, if that makes sense. We were always behind and kind of a little bit paranoid, but trying to enjoy the process at the same time.”

Leonard kept his sanity by reminding himself who he was playing for.

“When you hit rock bottom, it can’t get much worse,” Leonard said. “So every game, every week, every time you’re watching film, it’s like, you gotta figure out why you’re doing it. And it’s not for anybody’s satisfaction but yourself and the guys in the building.”

Leonard said during the season that he never saw what people said about him on the internet in September and early October. That much was true.

“I legit turned off socials,” Leonard said. “Didn’t even look at Safari the next few weeks after NIU.”

That was the easy part. The hard part was when people started to message his longtime girlfriend.

Leonard would also get texts and phone calls from high school coaches and others close to him that said, “Man, these people on Twitter” or “I’ve been getting in so many Twitter fights.”

“Like, thanks for reminding me that everybody hates me right now,” Leonard said, laughing again. “I kind of just tune it out. I’m like, ‘Alright, nobody even cares anymore.’ I just convinced myself that.

“But the hardest part is everybody around you has to deal with it.”

The mail and packages sent to Leonard’s house were difficult to confront, too, as were the boos and chants for his backup that rained down on him at Notre Dame Stadium.

Leonard said at the time that he and his teammates didn’t listen to the outside noise, and that he couldn’t let it bother him. But it did.

“Being a competitor, it’s tough to forget being at the home stadium and getting booed your first two games, and then just being like, ‘Oh, nothing happened.’” Leonard said. “It was very tough for me to play at home early in the season.”

As Leonard struggled on the field through the first half of Week 4 vs. Miami (Ohio) — two missed easy throws settled fan opinion early in that one — and the second half of Week 5 versus Louisville, he also struggled to balance not caring about what others thought with the goal of endearing himself to the fan base.

A Notre Dame fan growing up and a people pleaser by nature, Leonard loved a place that didn’t love him back.

“You get everything you ever wanted and your dream comes true. And you’ve given your heart out, and you don’t play as good as you want,” Leonard said. “And everybody’s booing and, ‘Oh my gosh, I’m sorry!’”

Sometime between Notre Dame’s first and second bye weeks, though, things started to change.

Leonard was playing better. He was on the same page with his offensive coordinator, Mike Denbrock, and his teammates. An offensive identity was established, and even if it wasn’t perfect, it was winning games.

Top 10

- 1New

Johntay Cook

Headed to ACC

- 2Hot

Fan who fell from stands

20-year old former CFB player

- 3Trending

Donald Trump

Wants Saban back as Alabama HC

- 4

Kentucky, St. John's

Set to play in 2025-26

- 5

Bracketology

Way Too Early Tournament projection

Get the On3 Top 10 to your inbox every morning

By clicking "Subscribe to Newsletter", I agree to On3's Privacy Notice, Terms, and use of my personal information described therein.

As the post-NIU streak hit four, five and six games, Leonard could do what he hadn’t done since early September.

“I was able to walk on campus with my head held high and be proud to be quarterback of Notre Dame,” Leonard said.

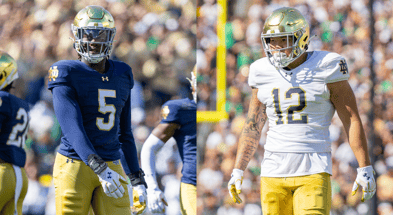

When Christian Gray and Xavier Watts ran interceptions back for touchdowns at Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum Nov. 30, a weight lifted off Leonard and the Irish’s shoulders.

The work wasn’t done, but the marathon-sprint of a regular season was over. They could have played any number of teams in the first round, so there was no point in preparing for an opponent until after Championship Saturday.

“Oh, we kicked back a little bit,” Leonard said. “That was a good week for us, just being able to enjoy each other and what we had accomplished.”

It was also a week to appreciate the fans who did stick with Notre Dame after NIU.

“Even the Purdue game, they showed out,” Leonard said. “And then going out to USC, shoot, there were so many Notre Dame fans at that stadium. They believed in us, and that’s kind of why we believed in ourselves.”

The real fun began during the College Football Playoff, starting with the first round against Indiana. He’ll remember Jeremiyah Love’s 98-yard touchdown run, but also the play that preceded it: His first pass in the College Football Playoff was an interception.

“I actually got off a Zoom with the team yesterday,” Leonard said. “They showed me that.”

Moving to the Sugar Bowl against Georgia, Leonard’s game-sealing third-and-7 run in which he leaped over star Bulldogs safety Malaki Starks is top of mind (“Not breaking my neck was a lot of fun”). Much more meaningful, however, was RJ Oben’s strip-sack that led to a touchdown pass to wide receiver Beaux Collins at the end of the first half.

Leonard and Oben go way back, even beyond their time as teammates at Duke. Their dads played together at Gonzaga High School in Washington, D.C., with Oben’s father eventually spending more than a decade in the NFL. Oben struggled to make an impact at Notre Dame until that moment, and Leonard knew it.

“I was so happy for him,” Leonard said. “That strip sack right there is well worth him coming to Notre Dame. Let’s say he doesn’t play all year, he does that one play. Like, well worth bringing him over.”

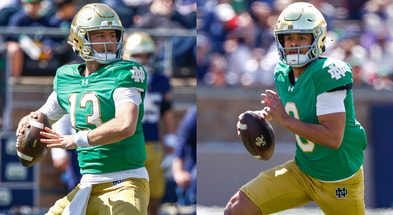

A week later, Leonard’s response to his 2 interceptions in the Orange Bowl against Penn State was an important personal milestone. Seeing Steve Angeli, with whom he is close, stepping in after he suffered a head injury and leading Notre Dame to an end-of-first-half field goal was a cool moment for him, too.

However, Leonard explained, the playoff run wasn’t about him.

“I think the coolest thing for me is being a part of the guys that have been there for four and five years, and seeing the smiles on their faces and all the hard work they’ve done pay off after every single win and every trip that we took,” Leonard said. “Notre Dame’s a tough place to go to school and play football, but guys have waited their whole career for this moment.”

Leonard would have been overwhelmed whether Notre Dame won or lost against Ohio State in the national title game, with it being his last time wearing a blue-and-gold uniform.

But after the Irish fell to the Buckeyes, his emotions reached a new level.

“Looking into my teammates’ eyes and hearing them say, ‘This was the best year of my life,’” Leonard said. “Or just a simple thank you kind of did it for me.”

Throughout a season of losing the fan base and winning it back, Leonard’s greatest fear was letting his teammates down.

They helped him fight through injuries during spring practice, when he later admitted he felt insecure about his absence — “Did they intend to have a transfer quarterback that just got hurt?” he said in August — and during the season. Every week, Leonard told himself, “I want to win this game for my guys.”

“For them to say thank you at the end of the season was definitely the most emotional I’ve been in a long time,” Leonard said.

Leonard walked into the locker room after his postgame press conference, his eyes red with tears. Only the players in that room could see him in that moment. They were the only ones who mattered.