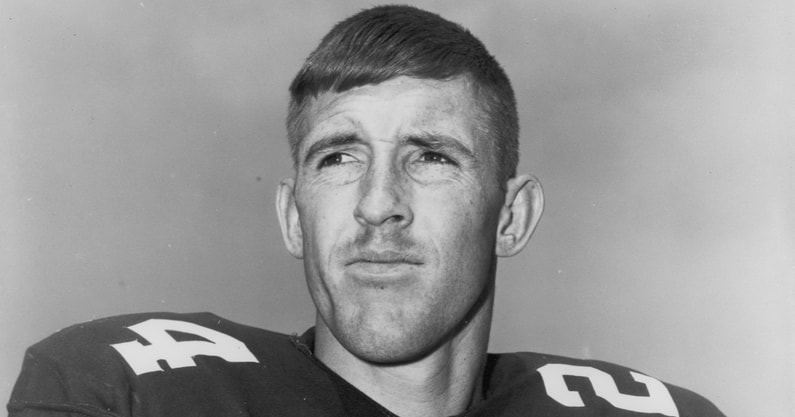

98 yards and a Cloud of Dust: Bobby Bryant reminisces about a legendary Gamecock, NFL career

Introducing South by Southeast – A Gamecock History Newsletter! Alan Piercy, a lifelong Gamecock fan and Carolina grad, will bring you an ongoing series spanning the history of Gamecock athletics, from the SEC, to the Metro/Independent years, to the ACC and beyond. A sepia-toned remembrance of all things Garnet & Black. Alan is the author of the upcoming book, A Gamecock Odyssey: University of South Carolina Sports in the Independent Era (1971-1991), due for release by USC Press in November 2023.

“Bryant picked up that punt down there at our goal line with me yelling my head off for him not to touch it.” – Gamecock coach Paul Dietzel

It was a beautiful day for opening a new stadium. The Gamecocks, 0-3 under first-year coach Paul Dietzel, were the first guests hosted by N.C. State in their plush new digs, 41,000-seat Carter Stadium (later renamed Carter-Finley). Raleigh News & Observer columnist Dick Herbert, in his game day column of October 8, 1966, called the venue “a stadium as modern as tomorrow and as lasting as time.” Charles Craven, Herbert’s colleague at the N&O noted, of the opening day events, “the weather was perfect, and the speeches were short. And the mob of 35,200 were well-behaved.”

Dignitaries, donors and fans gathered for pre-game ceremonies. A concert by the Wolfpack Marching Band gave way to dedication speeches by the Governor and university brass. Skies were clear and temperatures approached 72 degrees by the 1 p.m. kickoff. Pre-game fireworks scattered a herd of cows in a field behind the sparkling new press box. “They won’t give any milk for a week,” observed an Ag school worker, clearly unamused over the ruckus.

Herbert wrote of the Wolfpack’s stadium debut, “the setting was too perfect. Something bad had to happen. It did.”

In a day of firsts, the first play from scrimmage in the new stadium took the air right out of State’s celebratory mood, as the Wolfpack lost a fumble on their own 17-yard-line. In short order, Carolina’s Benny Garnto tossed a perfect halfback pass to Jim Killan in the end zone to take a 7-0 lead. The Wolfpack knotted the score at seven with a 32-yard interception return for a touchdown, and the score remained tied after one quarter.

When an early second-quarter drive stalled, the Wolfpack’s Jim Donnan punted from the State 40-yard-line. Carolina’s senior returner Bobby Bryant lined up about forty yards deep at the Gamecock thirty and waited to receive. Much like today, football coaches at the time taught returners not to field a punt inside the 10-yard line. Hoping to avoid a possible miscue deep in their own territory, they gamble instead for the more favorable result of a touchback.

“He kicked a low line drive that bounced way up in front of me,” the 79-year-old Bryant recalls now, “it was a nice wobbling ball coming down. I had gone back to get it, and I forgot all about that ten-yard-line rule,” he says laughing. “When it came down, I was on the two. So, I turned and started running, got a couple of good blocks, and I had a pretty good runback,” the ever-modest Bryant says of his 98-yard punt return for a touchdown. The touchdown put the Gamecocks up 14-7 and highlighted an improbable 31-21 road win, the only victory during an otherwise forgettable 1-9 season in Dietzel’s debut season at South Carolina.

Bryant’s thriller set a South Carolina and ACC record for longest punt return which still stands today.

An excited Dietzel told reporters after the game, “With this being their stadium dedication and all those people out there, North Carolina State was as high as they could be. We did get a couple of breaks in crucial situations,” adding with a toothy grin, “One of those breaks came when Bobby Bryant picked up that punt down there at our goal line with me yelling my head off for him not to touch it.” The coach continued, “But man, is he ever an athlete. He is just great, and a great kid too.” Dietzel called Bryant, “probably the best defensive back I’ve ever coached.”

A gifted athlete from the start

Bryant grew up one of 11 children, the son of a carpenter and a homemaker. “You had to be a homemaker with eleven kids,” Bryant recalls of his mother. “We had six girls and five boys, so we had a couple of teams right there.”

He excelled in football, baseball, and basketball in the Macon, Georgia, neighborhood where he grew up. Later, he was a standout in all three sports at Macon’s Willingham High School, where he also ran track.

“I was a skinny 145-pound halfback,” he says, “but I could run fast.” Indeed, Bryant earned the nickname “Bones,” for his lanky frame. At six feet, one inch, he never weighed more than 174 pounds in college, but was a naturally-gifted and highly-disciplined athlete.

Bryant was lightly recruited as a high school senior, earning scholarship offers from Tennessee-Martin and Presbyterian. But he also caught the eye of the University of South Carolina’s track & field coach, Weems Baskin. Baskin doubled as a football assistant under Gamecock head coach Marvin Bass, and had recruiting responsibilities in the state of Georgia.

When Carolina offered a scholarship, Bryant accepted. His debut in Garnet & Black came as a member of the 1963 freshman football squad during a time when freshmen were ineligible for varsity play.

He moved up to varsity in football and baseball as a sophomore in 1964-65 and showed flashes of the talent which would earn him All-ACC accolades later on. Playing both ways that season, he caught a 69-yard touchdown pass from quarterback Dan Reeves in a win versus Wake Forest.

Though he says he never saw a lot of action on the offensive side of the ball, Bryant was already showing brilliance as a punt returner with several long returns that season, including an 88-yarder versus North Carolina. Though that play was nullified by a penalty, “Bones” quickly earned notoriety for his speed and sure hands.

Bryant calls the ‘64 match-up with Georgia at Carolina Stadium probably the most memorable game of his college career. He was eager, he says, to show his home-state Bulldogs they had erred in overlooking him on the recruiting trail.

Indeed, he played inspired football that day, including punt returns of 24 and 42 yards and an interception in the end-zone, which snuffed out a third-quarter Georgia drive. The Gamecocks managed a 7-7 tie versus the heavily-favored Bulldogs. It was an outcome, Bryant says, which felt more like a win given the emotions of facing the team for which he had dreamt of playing as a young boy.

Bryant solidified a starting spot in the defensive backfield and as a punt returner by his junior campaign in 1965 and led the team that season with three interceptions. The Gamecocks finished 5-5 (4-2 ACC) and earned a share of the conference title with Duke, the program’s first ACC championship in any sport. However, in July 1966, the ACC stripped Carolina of its share of the title after it was discovered that head coach Marvin Bass had played three athletes who were ineligible under conference rules.

South Carolina was forced to forfeit its four ACC wins, after which Clemson and N.C. State, who both lost to the Gamecocks, earned shares of the ’65 conference championship. Though Carolina and NCAA records still reflect the 5-5 (4-2) record, Carolina lost its share of the title, while Duke, through no fault of its own, fell to third.

Following the ’65 season, Bass accepted a head coaching opportunity with the Montreal Beavers of the Continental Football League, a short-lived semi-professional American football league.

Carolina, meanwhile, turned to Paul Dietzel as head football coach and athletics director. Dietzel boasted a national championship resume (LSU, 1958), and came to Carolina after a successful four-year stint at Army. Of Dietzel’s arrival in Columbia, Bryant recalls, “We knew about his history… we were excited… we thought things were going to get a lot better.”

They would get better, but not in 1966.

Two-sport standout

Equally as talented on the diamond as the gridiron, Bryant accumulated a 16-7 record over three seasons as a starting pitcher for the Gamecocks. He went 4-3 as a sophomore and 6-2 as a lefty staff ace in both his junior and senior seasons.

His 4-3 finish as a sophomore was notable not just for a winning ledger but for what he overcame. Bryant underwent surgery to repair a broken wrist following the ’64 football season and trotted out to the mound in the spring of 1965 with a cast running the full length of his surgically-repaired right forearm.

“I tied my glove onto my cast, and the catcher would kind of lob the ball back to me,” Bryant says, “I got used to doing it and it worked ok, but in those days, the pitchers batted.”

Pitching with a cast on his non-throwing arm was one thing, but batting?

“I bunted over .300 that season. I was fast and a left-handed batter, so I found the biggest barreled bat I could find, this Nelly Fox model, and I was able to get the barrel on the ball pretty good,” pausing to consider the achievement before repeating in a tone of wistful nostalgia, “I drag-bunted for over .300 that year.”

Also notable during that sophomore campaign was perhaps Bryant’s most impressive outing of a stellar college career; a complete-game thirteen-inning 1-0 win over Maryland at College Park. He set a school record with 16 strikeouts in that game.

With a cast on his arm.

Despite a lengthy search of the USC baseball record book, there were no statistical rankings for innings pitched, strikeouts, or batting average while wearing a cast, but Bryant would no doubt dominate all three categories.

In an era before Bobby Richardson and June Raines vaunted Gamecock baseball into the national limelight, the program was led by a series of part-time coaches balancing other responsibilities at the university. Bryant played for three different head coaches during his varsity career. Jack Powers, who arrived for Bryant’s senior campaign of 1967 was “the first full-time baseball coach we had,” Bryant recalls.

Dick Weldon, an assistant football coach under Dietzel, coached the baseball team in 1966. “He was a funny guy,” recalls Bryant. “We never knew who was going to pitch until we showed up to the ballpark. But he would come up and hand me a baseball and say, ‘Bobby, you’re pitching today,’” adding with a chuckle, “so, about fifteen minutes before the game, I got warmed up.”

“My sophomore year (1965), our coach was Bob Reising, and he was an English professor,” Byant recollects, noting the “minor sport” status of baseball on campus at the time.

Asked about weight training facilities available to student-athletes in those days, Bryant says, “There was no such thing as a weight room. The only set of weights was kept in an equipment room, and it was just a bar and a bench and probably a couple hundred pounds of weights you could load onto it. Myself and a couple of the other guys would go downtown to the YMCA, and they would let us lift weights there, but that was all on our own.”

English professors doubling as part-time coaches, and a weight training program consisting of a solitary bench and dusty barbells sitting forlornly in a dark equipment room. It was a different time, indeed.

Playing facilities had a different feel at the time as well. By 1969, USC unveiled its brand-new spring sports complex, complete with an upgraded baseball diamond and a 2,500-seat stadium, along with The Roost athletic dorms and dining facility. But during Bryant’s time the baseball field was little more than a patch of grass, a couple of ramshackle dugouts, and temporary bleachers.

Carolina Stadium (now Williams-Brice) also bore little resemblance to the grand structure which now stands at Bluff Road and George Rogers Boulevard. Seating around 43,000 in Bryant’s playing days, the stadium was a hardscrabble assemblage of corrugated metal stands and wooden bleachers. It was not much changed from its Depression-era debut, save for modest expansions to end zone seating in the 40’s and 50’s. The team dressed in locker rooms located at the “Roundhouse” athletic offices on Rosewood Drive and bussed two miles to the stadium on game days.

It was a time of transformational change across campus. By 1966-67, Bryant’s final year at USC, bulldozers and cranes plied their trade as construction commenced on the 12,401-seat Carolina Coliseum. It was a facility which dwarfed the Gamecocks’ former basketball home, 3,500-seat Carolina Field House.

Top 10

- 1New

Arkansas upsets Kentucky

Cal wins in Rupp return

- 2

Reed Sheppard

Shows support for John Calipari

- 3

Tampering concerns

Nebraska likely to cancel spring game

- 4

Caleb Love headbutted

Multiple ejections in Arizona

- 5Hot

Bobby Hurley

Refuses handshake line

Get the On3 Top 10 to your inbox every morning

By clicking "Subscribe to Newsletter", I agree to On3's Privacy Notice, Terms, and use of my personal information described therein.

With a sharp increase in enrollment as the Baby Boomer generation came of age, the University expanded its brick-and-mortar footprint rapidly to keep up. There were 6,800 students at USC’s Columbia campus when Bryant enrolled as a freshman in 1963. By 1970, enrollment had more than doubled to 15,000.

In many ways, Bryant bore witness during his time in Columbia to USC’s evolution from small Southern college to modern university.

A fourteen-year NFL career

Bryant debuted with the Minnesota Vikings during the 1968 season, where he teamed with fellow newcomer Paul Krause in the Vikings backfield. The duo combined for 104 interceptions over twelve seasons together, balancing a dominant Viking defensive front, the famed “Purple People Eaters.”

The Vikings played their home games during those years in Metropolitan Stadium, an outdoor, multi-use venue the team shared with the Twins of Major League Baseball.

How does a Macon, Georgia, native by way of Columbia, South Carolina, adjust to playing in the notorious cold of Minnesota’s late season? “Good question,” Bryant answers.

Bryant relays a story about Bud Grant to explain his adjustment to the frigid Minnesota temperatures. Grant, a native of Superior, Wisconsin, is notable as the only athlete in history to have played in both the NBA and the NFL. He served as Vikings head coach during Bryant’s entire fourteen-year career in Minnesota.

“Bud told us a story about the Eskimo workers in Alaska and Canada working on the Defense Early Warning Line, set up to detect incoming bombers from the Soviet Union during the Cold War.

“American workers struggled with the cold, and would have to come in to warm up frequently. Meanwhile, Eskimo workers stayed out for hours on end.” Bryant continued, “Scientists studied their diet, their blood, and everything they could study to try and understand how they could withstand the cold weather. Studies eventually concluded there was no physiological factor. The indigenous people had simply developed an acceptance of the cold and were accustomed to working in those conditions.”

“He (Grant) told us, ‘We’re not going to have heaters,’ and we never did have heaters on the sideline. We couldn’t wear gloves. We practiced outside even in the worst of weather.” He says of Grant’s proclamation, “we didn’t like it, but we didn’t have any choice, so we got used to it.”

Bryant remembers it was a distinct psychological advantage, particularly over teams from warmer climes. “It was always good when we had freezing weather and there would be a team from Dallas or Miami or LA. We would have guys out there with no undershirts on, just short-sleeved jerseys over their pads,” he laughs, “and that really freaked a lot of those teams out. They would say, ‘something’s wrong with those guys, they’re crazy,” adding, “we didn’t lose many games in cold weather.”

Fourteen-year NFL careers are exceedingly rare. Particularly for lanky, 170-pound cornerbacks. Asked about the key to his longevity, Bryant cited discipline. “I was very disciplined from my youth. We had guys that were better athletes physically than I was, but may have been lazy, or didn’t study the playbook like they should have.” He recalls Grant didn’t tolerate mistakes, preferring older players who he felt were more stable, more focused and less prone to errors.

The Vikings were dominant during Bryant’s career, winning eleven of fourteen divisional championships and appearing in four Super Bowls in 1970, ’74, ’75 and ‘77. Though Bryant was a member of all four Super Bowl teams, he missed two of the four championship games due to injury.

Bryant played some of his best football in the post-season. During an NFC Championship game versus Dallas on December 30, 1973, he returned a Roger Staubach interception sixty-three yards for a touchdown, helping the Vikings to a 27-10 win and the franchise’s second Super Bowl berth.

During the 1976 NFC Championship game versus the LA Rams, he returned a blocked field goal attempt by Rams’ kicker Tom Dempsey 90 yards for a touchdown, propelling the Vikings to a 24-13 win and their fourth Super Bowl appearance in seven seasons.

Bryant was selected to the 1975 and ’76 NFL Pro Bowl teams. His 51 interceptions rank second all-time in Viking’s franchise history, only two behind his longtime backfield mate Paul Krause. When Bryant stepped away from the NFL following the 1980 season, his interception total ranked tenth in league history. In 2021, Bryant was included among the Fifty Greatest Vikings, in a commemoration of the franchise’s 50th anniversary.

A legacy of excellence at South Carolina

Fifty-six years after his final game in the Garnet & Black, the Gamecock football record book still whispers of his greatness. There’s the school (and ACC) record for longest punt return (98 yards). He also holds the program record for punt return average in a season (18.6 yards), set in 1966. He was named a permanent captain for the ’66 season, and earned All-America and All-ACC honors for that season as well.

His baseball accomplishments are no less impressive. Bryant was the first pitcher in Carolina history to strike out one hundred batters in a season. He earned All-ACC honors in 1967, and also set the program record for strikeouts in a game (16). Though that record was broken in 1972 (17), Bryant’s tally still ranks second. He was drafted by the New York Yankees in 1966, and by the Boston Red Sox in 1967, though in both instances he opted for a return to football.

In 1967 Bryant received the Bryant J. McKelvin Award, recognizing the top overall athlete in the Atlantic Coast Conference. Bryant was the only Gamecock athlete to be recognized with that award during South Carolina’s eighteen years in the ACC.

His exploits as a two-sport star in Garnet & Black are without equal. Given the significance of his accomplishments, records-set, All-America and All-ACC recognitions, as well as ACC Athlete of the Year accolades, Bryant arguably earned recognition beyond his 1979 induction into the South Carolina Athletics Hall of Fame.

In this writer’s opinion, Bryant’s No. 24 jersey should have been retired decades ago. His name belongs inside Williams-Brice Stadium, enshrined alongside the likes of Wadiak, Rogers, Sharpe, and Clowney. Moreover, there is not a single retired jersey from the entire nine-year Deitzel era. Perhaps Dietzel was not prone to such recognitions. But the University has established criteria to standardize the process, and Bryant is more than qualified, more than deserving.

Arguably, Bryant completed the greatest NFL career of any player in the history of the Gamecock program, given his longevity in the league, eye-popping statistics, Pro Bowl selections and participation in multiple Super Bowls.

Talking with him, the uninitiated might never suspect his former exploits. He is a soft-spoken man, humble, unassuming and kind. In our era of chest-thumping puffery by lesser men in public life, these attributes only serve to accentuate his greatness.

Following his NFL career, Bryant returned to Columbia, where he worked as a sales representative in the auto glass industry for many years. In 2010 he appeared in a television ad for Quackt Glass, where he good-naturedly tossed a football to “Ducky” the company’s costumed mascot. Then 66, Bryant was fit, trim, and looked not far removed from his 170-pound NFL frame of thirty years prior. Discipline defines him still.

He remains a die-hard Gamecock fan, and enthusiastic about what Coach Shane Beamer is building in Columbia.

As for that 98-yard punt return record… well, after 56 years, it seems that might never be broken.

Though if it ever is, Bryant will be right there, cheering on his beloved Gamecocks.