Cocky and the Leprechaun: A brief history of the South Carolina-Notre Dame football series

Note: The following was written by Alan Piercy, author of the forthcoming book, A Gamecock Odyssey: South Carolina Sports in the Independent Era (1971-1991), scheduled for publication by USC Press, Fall 2023.

“USC – Irish Football Series Set,” proclaimed the headline of a modest three-paragraph article in the March 21, 1973 edition of the Columbia Record, the Capital City’s long-shuttered evening newspaper. It was nearly lost among more pressing news of that early spring, including reports from the NCAA basketball tournament, where John Wooden’s UCLA Bruins were on their way to a tenth national championship, and seventh in a row.

Gamecock football coach Paul Dietzel prepared to lead his team into spring drills in his eighth season at Carolina. Beyond the sports world, Viet Cong officials announced the release of 32 American POWs as the calamitous Vietnam War wound to a close. And the Ford Motor Company issued a recall for ’73 model Torinos and Pintos, citing various manufacturing defects.

Frank McGuire’s basketball Gamecocks had bowed out of the NCAA tournament a few days earlier following a second-round loss to Memphis State. The loss sent the Gamecocks to a consolation game, back when the NCAA did such things, and then home to Columbia. No one could have imagined it then, but the consolation game victory versus Louisiana would be McGuire’s final NCAA tournament win, and the program’s last for over four decades.

Just a few weeks prior, McGuire’s Gamecocks had lost a 73-69 nail-biter to Digger Phelps’ Notre Dame squad at South Bend. It marked South Carolina’s first loss in the series, after winning the first three. In those nascent days of independent status, McGuire looked to replace the incandescent rivalries of former ACC foes with a national schedule, including the likes of Phelps’ Irish, Al McGuire’s Marquette Warriors, and Jerry Tarkanian’s UNLV Rebels, among others.

Likewise, Dietzel looked to elevate the Gamecocks’ football schedule to include the biggest names in the game. By the early 70s, Dietzel had inked future matchups with the likes of Michigan and Southern California, and ongoing agreements with budding national power Florida State, and Louisiana State, the program he had led to a national title in 1958. Notre Dame represented the biggest name of them all, with its history and lore and unparalleled national profile. The series was emblematic of Dietzel’s ambitions for his program and for the athletics department he was integral in leading out of the ACC two years prior.

Despite a promising 7-4 campaign in 1973, which included a 32-20 season-ending win over archrival Clemson, Dietzel announced he would resign following the ’74 season after a disappointing 0-2 start. After unquestioned success at elevating Carolina’s athletic facilities across the board in his role of athletics director, Dietzel’s results as head football coach had been more modest, with a 42-53-1 record over nine seasons, leaving university officials and fans anxious to move in a different direction.

Enter Jim Carlen, the swaggering, often combative coach from Cookeville, Tennessee, by way of prior stops at Texas Tech and West Virginia. Carlen’s Mountaineer squad had dispatched Dietzel’s Gamecocks in the 1969 Peach Bowl at Atlanta’s rain-soaked Grant Field, and now he inherited Dietzel’s dual roles of athletics director and head football coach at South Carolina. Carlen also inherited Dietzel’s ambitious future schedules, which the pugnacious Carlen fully embraced.

After a promising 7-5 result in 1975, including a 56-20 thrashing of Clemson, and a Tangerine Bowl invitation, just the third bowl trip in program history, optimism reigned for Carlen’s second stanza in 1976. After a 5-2 start, including an upset of No. 16 Ole Miss in week seven, South Carolina earned its first national ranking under Carlen, coming in at No. 19, and setting the stage for a top-20 clash with the No. 12-ranked Irish.

1976

That first Gamecock-Irish matchup was an eventful one, both on and off the gridiron. President Gerald Ford was scheduled to visit Columbia and provide ceremonial halftime remarks to the sellout crowd of 56,000.

Less than two weeks before the November 2nd Presidential election, polling was tight between Democratic challenger and Georgia Governor Jimmy Carter, and the incumbent Ford, the former Vice President under Richard Nixon, who had ascended to the Presidency following the Watergate scandal and Nixon’s subsequent resignation in 1974

Ford’s Columbia visit was part of a late-campaign Deep South swing, as the President looked to solidify his standing in Carter’s native region. Following halftime remarks, he was scheduled to press the flesh in a highly orchestrated visit to the State Fair.

It was a near-perfect autumn afternoon, sunny and dry, with temperatures approaching 65. The deep-fried aromas of funnel cakes and corn dogs wafted across Stadium Road on a mild northerly breeze from the fair next door, mixing with sweet tendrils of tobacco smoke. Cigarettes were still available at concessions stands at the time, $.50 for a pack, right alongside Coca-Cola and Cromer’s peanuts.

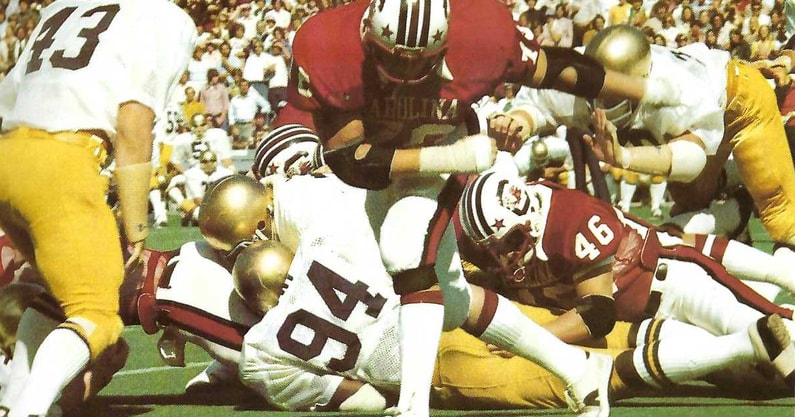

The Gamecocks took the field to the boom of a mini-cannon in those days before “2001”, clad in the garnet mesh jerseys of the day, and the Carlen-era white helmets, with large “Block-C” logos and garnet facemasks. The Irish were resplendent in their road-white jerseys and trademark gold helmets, which glinted brilliantly in the October sun.

Fans noted an obvious size discrepancy between the teams during warmups, with Carolina at a disadvantage across the lines of scrimmage, averaging 237 on the offensive line to Notre Dame’s 253, and 217 along the defensive front to 241 for the visitors. Back in South Bend, redshirt junior quarterback Joe Montana listened for radio updates, having suffered a shoulder injury before the season.

In a low-scoring affair, the Irish jumped out to a 10-0 lead in the first quarter, with the teams trading second-quarter field goals for a 13-3 score at the half. Defensive coordinator Richard Bell made halftime adjustments that stifled the potent Notre Dame offense, holding it scoreless the rest of the way. The Gamecocks pulled to within 13-6 early in the fourth, courtesy of a 35-yard Britt Parish field goal, his second of the day.

Carolina threatened again late, driving deep into Irish territory, but an interception at the Notre Dame 15-yard line halted the march, sealing the visitors’ win. The Irish defense had kept record-setting Carolina quarterback Ron Bass and the Gamecock offense out of the endzone, tying an NCAA record at the time of 20 straight quarters without allowing a touchdown.

The Gamecocks would fall out of the rankings following the close loss, before reappearing at No. 20 two weeks later after a home win over N.C. State. Disappointing losses to Wake Forest and Clemson ended the season on a sour note, and despite a winning 6-5 ledger, the Gamecocks were left out of the post-season picture in those days of bowl scarcity. Notre Dame, meanwhile, went on to a No. 11 final ranking in the AP Poll following a 9-3 finish, including wins over No. 10 Alabama and a Gator Bowl victory over No. 20 Penn State.

1979

The ’79 season started with a road trip to former ACC foe North Carolina, which resulted in a surprising 28-0 shutout loss to what proved to be an excellent Tar Heel team. Junior George Rogers had moved to the starting tailback spot after a preseason injury to Johnnie Wright, and the UNC defense held him to 98 yards in that first game. It would be the final sub-100-yard performance of Rogers’ legendary career, which would climax with the Heisman Trophy in 1980. The Gamecocks got it going after the debacle in Chapel Hill, reeling off five-straight wins, including a 27-20 win at Georgia, the program’s first win between the hedges since 1958.

Now 5-1, Carolina traveled to South Bend, Indiana, for the first time ever to take on the Irish, who sat at 4-2 and No. 14 in the polls. In another low-scoring slugfest, the Gamecocks led 17-3 late in the third quarter before a frantic Notre Dame comeback edged Carlen’s squad by the thinnest of margins, 18-17. On the final drive, Irish quarterback Rusty Lisch connected with tight end Dean Masztak for a touchdown to pull within one, 17-16. With overtime rules in college football still 17 years away, the Irish lined up for a two-point conversion. Lisch’s pass was true again, connecting with flanker Pete Holohan for the conversion and win as time expired.

The loss was a bitter pill for Carlen and the Gamecocks, who had controlled the tempo and momentum for most of the afternoon with a grinding run game. Rogers split time in the backfield with Spencer Clark, as the two racked up 113 and 117 yards, respectively. It was all for naught, though, and USC athletics historian Tom Price wrote of the outcome, the Gamecocks “found out what it was like to be stabbed in the heart by a leprechaun.”

1983

After a tumultuous two-year period, which included the firing of head coach Jim Carlen after a 6-6 campaign in 1981, and the single-year stint of his successor and former defensive coordinator Richard Bell in 1982, a dismal 4-7 campaign, the Gamecocks turned to their third head coach in as many years.

When former New Mexico State head coach Joe Morrison accepted the USC job prior to the ’83 season, a reporter asked him if he felt intimidated by a schedule that included the likes of Georgia, Southern Cal, Notre Dame, LSU, Florida State, and Clemson. “Heck no,” Morrison replied, in his refreshingly “aw shucks” manner, “I’ve never seen Southern Cal and Notre Dame play in person. I’m looking forward to seeing them.”

The new coach quickly endeared himself to Gamecock faithful with his cool, low-key style and quiet confidence. His demeanor seemed a balm for fans after sixteen years of the loquacious salesman, Dietzel, and the territorial pugilist, Carlen, whose hegemonic ambitions and clashes with trustees, administrators, and fellow coaches often outnumbered wins. Morrison just wanted to coach football.

But he did more than coach football. Morrison ushered in the modern era of Gamecock athletics, from the introduction of the “2001” stadium entrance, to black uniforms, catchy slogans, and unprecedented success. The former NFL star, whose No. 40 had been retired by the New York Giants, soon made Gamecock football “cool,” perhaps for the first time ever.

Morrison abandoned the Gamecocks’ traditional white helmets for garnet, with black facemasks and a smaller “Block-C” and Gamecock emblem against a circular field of white. “Gamecocks” replaced “Carolina” emblazoned across the jersey chest. The coach commissioned team dentist Bill Smith, a talented graphic artist, to design the new uniforms, a snazzy sartorial upgrade. A professional look. Morrison was putting his stamp on the program early. Despite the 24-8 opening-season loss to the Tar Heels, a compelling new era of Gamecock football had begun.

Top 10

- 1New

Baseball Top 25 projection

Massive Top 10 shakeup

- 2Hot

Shedeur Sanders prank

Son of NFL DC admits guilt, apologizes

- 3

Falcons release statement

Involvement of DC in Sanders prank

- 4Trending

Jalen Milroe warns

Teams that passed on him

- 5

Tyler Warren pranked

Tied to Shedeur Sanders call

Get the On3 Top 10 to your inbox every morning

By clicking "Subscribe to Newsletter", I agree to On3's Privacy Notice, Terms, and use of my personal information described therein.

The Gamecocks sat at 2-2 after four games, the same record as the ’82 team at that point in the season, but things felt different within the program. Morrison’s Gamecocks were playing with great effort and enthusiasm. The team seemed to be having fun, and fans were buying into Morrison and his program. Energy and optimism were palpable.

A surprise 38-14 trouncing of “the other USC,” perennial national power Southern Cal in game five followed on a wild night at Williams-Brice Stadium, in which the east-upper deck actually swayed following a pivotal third-down stop late in the game. The swaying, which engineers explained as “harmonic resonance,” was a design feature of the structure, but no less disconcerting to fans in the lower-east deck who witnessed it. Told of the incident, Morrison famously quipped, “If it ain’t swayin’, we ain’t playin.’” The audible whir of printers soon followed as the instantly iconic quote showed up on t-shirts and bumper stickers around Columbia.

Now 3-2, the Gamecocks had the opportunity to knock off two iconic programs in a row, as Notre Dame came to town for the third game of that four-game series inked by Dietzel those many years ago. A rainy night in Columbia and a potent Irish offense dampened any thoughts of a second-consecutive big-name upset, as the Irish won 30-6 on a mostly forgettable evening for Gamecock fans.

The Gamecocks would finish 5-6 on the season, but bigger things lay ahead.

1984

In Tom Price’s 1985 book, Fire Ants and Black Magic, recounting Carolina’s magical 10-2 campaign of ’84, Price relayed the story of a conversation between team dentist Smith and the Gamecocks’ All-American linebacker James Seawright, which demonstrated that the history and tradition which is so often the focus of fans and sportswriters doesn’t always resonate with 19 and 20-year-old players. During warmups, before the road contest at Notre Dame, Smith asked Seawright if he knew that he was walking on hallowed ground.

“What does that mean,” Seawright asked, according to Smith’s telling afterward. “This is where the Four Horsemen rode,” Smith retorted, “This is where the Gipper played. This is where Knute Rockne coached.”

“Means nothing to me, ‘cause they’re all dead,” Seawright deadpanned.

Meeting with reporters after the game, Seawright expanded. “That tradition stuff doesn’t bother me. This felt the same as any other game.”

The Gamecocks and Irish met in a cold drizzle, under battleship-grey South Bend Skies. Despite the rain, 59,075 fans filed in before kickoff, the 105th sellout in 106 games at Notre Dame Stadium, dating back to 1964. An estimated 5,000 Gamecock fans made the trip, their garnet and black ponchos a distinct block, surrounded by Irish blue and gold.

Carolina took an early 7-0 lead on quarterback Allen Mitchell’s sneak from the one-yard line, capping a 31-yard drive after recovering an Irish fumbled punt a few plays earlier. The score was tied at 14 late in the second quarter before a long Notre Dame field goal provided them a slim lead, 17-14 as the halftime whistle blew.

The third quarter began in disastrous fashion, as the Gamecocks turned the ball over on their first three possessions, two fumbles, and an interception, leading to ten Irish points on a field goal and touchdown. When Notre Dame opted to go for a two-point conversion after the touchdown, Carolina’s Bryant Gilliard sacked quarterback Steve Beuerlein on a safety blitz, leaving the score 26-14 late in the third period.

A one-yard sneak by back-up quarterback Mike Hold capped a 16-yard drive by the Gamecocks, and tailback Kent Hagood barreled in for the two-point conversion just a minute into the final period, pulling the Gamecocks within four, 26-22. After trading turnovers, South Carolina regained possession at their own 25 with 12 minutes remaining. Carolina moved the ball to the Irish 33, helped by a face mask violation on the home team. From there, Hold narrowly avoided a sack before setting off on a mad scramble to the end zone, pushing Carolina into the lead, 29-26 after the Scott Hagler point-after.

On the ensuing possession, Gamecock safety Rick Rabune recovered an Irish fumble at the Notre Dame 17-yard line, and tailback Quinton Lewis took it in for a seemingly comfortable 36-26 lead with seven minutes remaining. Notre Dame would not go away quietly, though, and pulled to within four at 36-32 after another late touchdown and failed PAT. But luck and time would finally run out on the Irish, as South Carolina held on for a historic win, moving to 6-0 for the first time in program history.

In doing so, the Gamecocks had finally vanquished that leprechaun that had bedeviled them in the three earlier matchups. As Price put it, “the Gamecocks had slogged through the rain, in the shadows of the Golden Dome, and ‘Touchdown Jesus,’ and had conquered a legend.” Even the normally stoic Morrison couldn’t contain his enthusiasm during a post-game press conference, telling reporters with a wide grin, “Damn, it’s exciting when you take Georgia, Pittsburgh, and Notre Dame in the same year.”

Sports Illustrated’s Jack McCallum, who had spent the prior week in Columbia covering the upstart Gamecocks, wrote of the feeling which settled over Notre Dame Stadium after Carolina’s final score, “…in the next moments, the sense of one school on the rise, the other in decline, was inescapable.”

The Next Chapter

The Gamecocks and Irish will meet for the fifth time in the Gator Bowl on Dec. 30. Ironically, it will also be Carolina’s fifth appearance at the Jacksonville-based bowl.

The Gator has both given and taken away from Gamecock football over the years. It was the location of the program’s very first bowl appearance on Jan. 1, 1946, in the inaugural Gator Bowl contest. There were only eight bowl games then, including the short-lived Oil Bowl in Houston (there are a staggering 42 bowl games in 2022). The Gator Bowl was also the site of Gamecock bowl visits in 1980, ’84, and ’87, all Gamecock losses, marking four of Carolina’s horrendous 0-8 start in bowl contests.

Though Carolina has fared better in postseason play since that last visit to Jacksonville in 1987, winning 10 of 16 subsequent bowl appearances, the Gator still haunts Gamecock fans old enough to remember. Can Shane Beamer’s Gamecocks reverse 76 years of futility in Jacksonville, and vanquish that pesky Leprechaun once again?

We’ll know in just a few days.