Musings from Arledge: USC Defense in Shambles

Any team that wants to be elite, that wants to be a legitimate playoff-level team, eventually has to show that it can stop somebody.

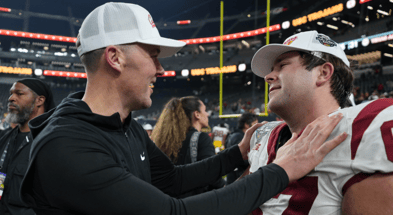

The Trojans are loaded offensively. Caleb Williams is an elite talent. Travis Dye is an elite producer who is far better than the sum of his parts. The receiver room is deep. The offensive line has been very solid, even with the injury issues. Lincoln Riley is considered an offensive guru for a reason.

The offense isn’t perfect. For stretches last night there seemed to be a lack of intensity, and the offense still has failed drives that probably shouldn’t fail. When an offense is as good as USC’s, it feels like no drives should fail.

Well, in the coming weeks, USC probably can’t afford to have any offensive drives fail. Because this defense is in full meltdown. After last night, we are officially witnessing defensive Chernobyl.

Early in the year the defense was giving up a lot of big plays but was also making a lot of big plays. Forced turnovers and solid red-zone defense were covering for the fact that USC’s defense consistently gives up yards in big chunks to every offense it plays. But the defense was at the top of the conference in scoring defense, and we consoled ourselves with that fact. Stopping the others team from scoring points is the most important thing, right?

Those days are gone.

Against Utah, the defense was gashed for almost the entire night. But Utah’s offense is good, and the officials screwed USC with two inexcusable calls. So the numbers were bad, and the fact that USC let the same guy beat them all night — a guy that had never done anything like that to anybody else — was a big red flag. But, still, we had hope that it was a one-time deal.

Then USC got shredded by Arizona. And we told ourselves that Jayden de Laura and his receivers are very good. And they are … but Utah had little trouble keeping them out of the end zone, and the Wildcats are 1-5 in conference play. It’s not like those guys can actually beat anybody.

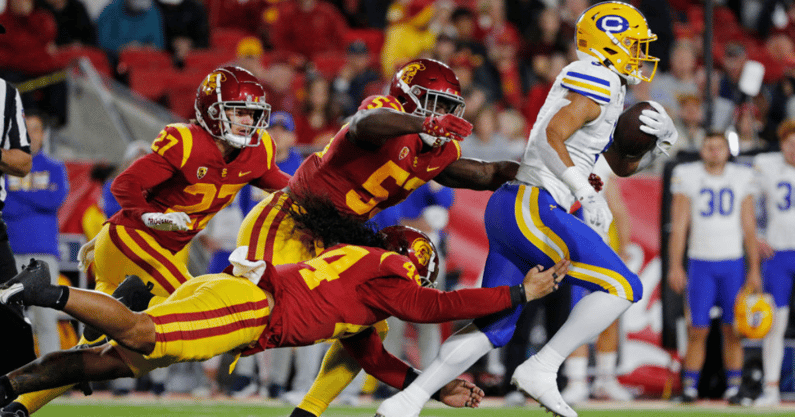

And then Cal came to town. USC’s defense got a home game against a perfectly fine, journeyman quarterback and a program that has struggled offensively since around 2005. A team that scored 20 points against UNLV, nine against Washington State, only 13 in an overtime loss (!) to Colorado — a legitimately bad offensive football team. If anybody was set up to get the defense some momentum, some confidence, this was it. If anybody was going to give USC a breather for once, a game where the starters could watch the fourth quarter, this was it.

And the Trojans defense gave up over 400 yards passing and likely came within an onside kick of losing to a conference bottom feeder and blowing up this promising season in spectacular fashion. USC’s defense gave up touchdowns on four of Cal’s last five offensive possessions, all on long drives. And the last three Cal drives — each resulting in a touchdown — came at a point in the game where a single stop would effectively end the game. And they couldn’t get one.

Early in the year, USC couldn’t stop the run but was playing pretty well against the pass. Now things have flipped. USC is playing much better against the run over the last month, but I’m not sure they could stop a passing attack led by Uncle Rico and ten dudes picked from the stands at random.

The truth is — and you won’t like hearing this — USC’s defense is bad. They’re not struggling a little bit. They’re not coming around but still making too many mistakes. They’re bad. And it’s hard to imagine the Trojans running the three-game gauntlet of UCLA, Notre Dame, and a conference championship game unless they get dramatically better very soon.

I think we all knew that the defense was a major question mark coming into this season. But Lincoln Riley’s immediate success turning around the offense and putting USC into conference title and even playoff contention has dramatically raised expectations, perhaps unfairly. But that’s what Riley came to USC to do, and he never backed off of those high expectations. So the spotlight is bright, just like Lincoln Riley wanted it to be. And in this light, it’s impossible to miss the truth about USC’s defense. It is in shambles. Lincoln Riley knows it. Alex Grinch knows it. Donte Williams knows it. The players know it. Everybody knows it; you can’t really pretend otherwise after last night.

Lincoln Riley will win a ton of games at USC. Nobody doubts that. Whether he will do what he wants to do — build a national powerhouse that can compete with teams like Alabama, Georgia, and Ohio State — depends on whether he can build a defense that at least approaches the consistent quality of his offenses. He didn’t do that at Oklahoma. And, right now at least, he is light years away from doing so at USC. This USC offense can score on anybody. They are absolutely capable of beating UCLA, Notre Dame, and Oregon. But to do so they’ll have to score on virtually every possession. Because they simply cannot rely on their defensive teammates to stop any offense with a pulse, or in Cal’s case, an offense without a pulse.

I don’t want to talk about Colorado. Colorado is awful. And, yes, they will probably have their best offensive performance of the year next week at the Coliseum, but I don’t think anybody believes Colorado will actually win that game.

So let’s talk a little about how to deal with UCLA’s offense, which everybody knows will pose a major challenge to USC’s defense. (Just as USC’s offense will be a major challenge for UCLA’s defense.) One of the major issues will be dealing with Dorian Thompson-Robinson, a very mobile quarterback. USC has recently struggled with two mobile quarterbacks.

Whenever teams face a mobile quarterback, one of the major questions fans ask is whether they’ll use a spy and, if so, how that works. A spy, of course, is a player dedicated to stopping a QB scramble on a passing play. So let’s talk about spying the quarterback, the theory behind it, and how spying has changed in recent years.

To do that, let’s start with a basic principle relevant to QB spying and defensive football in general: space. The enemy of any would-be tackler is space. Space gives a ballcarrier options, and the more options he has, the more difficult he will be to tackle. This is why open-field tackling is so difficult. With great ballcarriers, tackling in the open-field can be next to impossible. You could probably count on one hand the number of times Barry Sanders was tackled by a single defender in the open field. That’s not because of a lack of athleticism or skill from his opponents. He was playing against the best in the world. It’s because a great ballcarrier in space has a huge advantage over his opponent.

Imagine a standard off-tackle running play where the ballcarrier is trying to get through the hole. If the defender fills the hole and meets the ballcarrier there, he is far more likely to make the tackle, because the ballcarrier has very little space in which to operate.

But now imagine he’s just a little bit late getting to the hole, and the ballcarrier now has substantially more space, and therefore more options. In the hole, the ballcarrier may have two yards in which to maneuver. But if the defender is just a little bit late, that space may increase to four yards. With each additional split second that it takes the defender to arrive, the ballcarrier’s space increases, like a widening cone. Even an average NFL linebacker has a high likelihood of tackling Barry Sanders if Sanders has two yards of space in which to maneuver. Increase that space to six or eight yards, and the defender’s chances of success start to evaporate quickly.

Top 10

- 1

Coaches Poll

Auburn drops again in new Top 25

- 2New

Baseball Top 25

New No. 1, big shakeup

- 3

UNC bias

NCAA Tourney controversy

- 4

Pat Kelsey

Rips NCAA Selection Committee

- 5Hot

NCAA Tournament Bracket

The field is set!

Get the On3 Top 10 to your inbox every morning

By clicking "Subscribe to Newsletter", I agree to On3's Privacy Notice, Terms, and use of my personal information described therein.

Another advantage for the defender is when the ballcarrier is approaching the sideline. The sideline takes away space. A defender who keeps inside leverage (so the ballcarrier can not cut back without running into the defender) can — if he keeps the right angle — make a tackle on the sideline or force the ballcarrier out of bounds.

I say all this to identify the first fundamental problem of a traditional spy technique, where the defender waits behind the line of scrimmage and tries to mirror the quarterback. With that approach, the defender has to cover every conceivable gap that could arise — outside runs to the left and right, and runs up the middle between every rusher. Because the defenders are getting upfield, the gap the quarterback chooses will often be many yards behind the line of scrimmage and, therefore, there will be many yards between the spy and the quarterback. The spy will be left with what amounts to an open-field tackle, and that’s often a disaster. You only spy great athletes, and if your spy technique leaves your defender trying to tackle a great athlete in space, you’re sitting yourself up for failure.

There is a second problem: a traditional spy deprives the defense of either a rusher or a pass defender. Essentially, the defense has to play with one less guy because they are devoting one defender to watching the quarterback, when he would ordinarily be rushing the passer or defending the pass. This means that even if you stop the quarterback from running, you are essentially playing 10 on 11.

This is why many coaches have been slow to use a spy unless they are desperate. Instead, they might tell their pass rushers to simply contain the QB in the pocket. Don’t get upfield, or take risks, or open lanes; just keep him inside the pocket. The problem, of course, is that in modern football, a lot of these running quarterbacks are also very good passers. Imagine leaving Caleb Williams in the pocket with an unlimited amount of time. Do you feel good about your secondary’s chances?

It was this dilemma that led Nick Saban to design a fairly novel approach to the spy called the odd mirror defense.

The idea behind this approach is not to keep the quarterback in the pocket. The idea is to flush the quarterback out of the pocket — to make him leave — but to make him leave to a particular location and have the spy meet him there.

Generally speaking, you want the quarterback to be flushed outside (not in a gap in the middle), and as a general rule, you want to flush a quarterback to the side where he must throw against his body. So with a right-handed quarterback, you want to flush him to his left. The spy is not expected to cover any potential gap the quarterback may choose. Instead, his job is to fake a rush and then stay near the line of scrimmage where he can quickly track down the quarterback. And note that the quarterback in these situations is being flushed toward the sideline, so the spy can, if necessary, take a good pursuit angle and use the sideline to keep the ballcarrier in check. If done right, you’re not asking him to make an open-field tackle at all.

To make this strategy work, however, your other rushers (usually three of them, but it could be four or more) must flush the quarterback. If you want to flush the quarterback to his left, you have to collapse the pocket on his right and up the middle. If you don’t, he can stay in the pocket, take his time, and complete a pass. And the spy does no good if the quarterback can find another gap in the defense. In this case, you could imagine Nick Figueroa and Tuli Tuipulotu being primarily responsible for collapsing the pocket in the middle and on the quarterback’s right in order to flush him outside to the left. If they fail, the strategy fails.

Note that you can combine this strategy with the stunts that we often see from USC’s defensive line; imagine Figueroa stunting from the end position into the center of the line to collapse the pocket in the middle, while the linebacker who was lined up inside stunts outside and waits for the quarterback to be flushed. You might also see Tuli off the line as we saw against Arizona, where he can pick any spot in the middle of the line, making it harder for the defense to get two defenders on him and easier for Tuli to collapse the pocket.

If this strategy works, you need a good athlete but not a great athlete to do the spying. You don’t need to use Eric Gentry, for example, although you could. But Gentry is so valuable in pass coverage that I wouldn’t want to waste him as my spy. I would rather use the other linebacker who, while not as athletic as Gentry, can succeed because he knows where the quarterback will be and knows that he’ll be running toward the sideline to his left. This allows him to overcome some of the athleticism deficit and still be effective.

Other than how poorly USC played defensively, that was a pretty good day of college football.

I don’t root for Notre Dame very often. But I was yesterday. Clemson’s schedule is embarrassing, and it should have been obvious to everybody that the Tigers’ offense is weak and therefore that Clemson was not really a playoff team. They needed to lose. I was glad to see it happen.

I don’t root for LSU very often. But I did yesterday. Alabama with two losses is always a good thing. And the truth is that the Tide could have more than that. They almost lost to Texas and Texas A&M, and they have a road game at Ole Miss next week. This Alabama team was one of the heaviest preseason national title favorites in history. This must be a bitter pill for Saban and Tide fans. Sad, no?

Please watch my solo Musings show on YouTube when it comes out Wednesday. I will attempt to answer the most important question facing America today: Is it really true that UCLA sucks?