This season, home is where the wins are – along with truly loud crowds

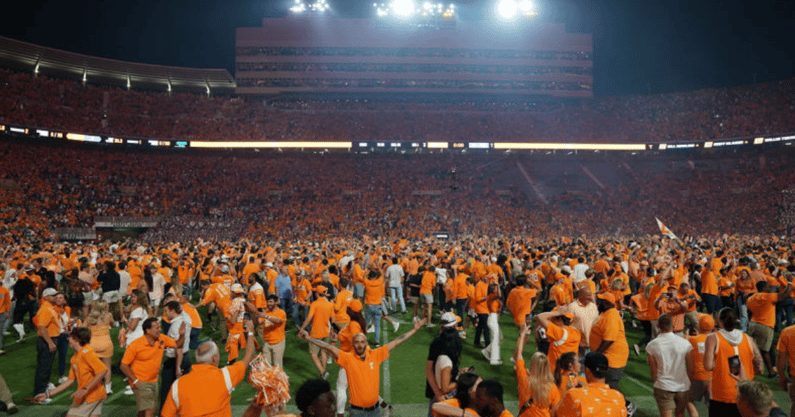

The signature sight of the 2022 season may be the blimp shot of the standing-room-only crowd on the field at Neyland Stadium after Tennessee beat Alabama.

The signature sound of the 2022 season is a roar, something akin to what you hear on a LaGuardia runway or sitting in the first 10 rows of a Metallica concert or – here it is again – what you heard at Neyland as the Volunteers ended a 15-game losing streak to the Crimson Tide.

If it feels as if college football is louder this season, that’s because it is. And if it feels as if that noise is affecting the outcome of games, that’s because it does. College football has a hearing issue.

If you saw how the 92,746 fans at Sanford Stadium remained in place Saturday, screaming their lungs out through a driving second-half rainstorm, you know that fans are making a difference. If you saw Tennessee’s seven false start penalties at Georgia, or Ohio State’s one false start and three delay of game penalties at Penn State the week before, or Alabama’s four false starts and two delay of games at Neyland two weeks before that, you know. This season, “sound defense” is something offenses need to play.

The noise levels make a mockery of the stratagem of piping in crowd noise during weekday practice. Every coach does it, and it doesn’t come close to mimicking what the visitors encounter on Saturdays when they step on the field.

I’m not just shouting into the void here. The numbers back up this supposition.

The number of false start penalties is up 9 percent over last season. Teams are committing 2.8 false starts per game, the most of any infraction, said Steve Shaw, the NCAA coordinator of officials. He added that in the Power 5 conferences, the visiting team is committing 56 percent of the false starts. If the games I’ve covered this season are any indication, I’m surprised that percentage isn’t higher.

The home team in the FBS this season is 420-217 (.659), the highest winning percentage since the NCAA began keeping these numbers in 1966. Where else does a home-field advantage start but with the crowd?

It’s one thing to measure the effect of a home-field advantage, quite another to determine why fans are louder. SEC commissioner Greg Sankey believes crowds have been louder since the return from the pandemic season of 2020.

“I thought it was that I had forgotten what crowds felt like during COVID,” Sankey wrote this week in an email. But he doesn’t believe the decibel level has dropped this season. His next remark echoes “It just means more,” the league slogan.

“It just feels louder,” Sankey wrote.

Derek Mobley is the director of ABC’s Saturday night college football telecasts. He worked the Alabama-LSU game in Baton Rouge last week.

“I really feel like your college football fan is even more passionate, if that’s possible,” Mobley said. “They seem more appreciative of how a big-game atmosphere is. … I kind of thought last September (2021) would be kind of crazy because people would have pent-up energy. I do think it’s more this year.”

Top 10

- 1New

Ohio State investigation

Defensive coach on leave

- 2Hot

Chris Ash

ND hires veteran coach as DC

- 3

Texas-sized spending

Longhorns break records

- 4

Calipari on Kentucky return

'I got bazooka-holes in my body'

- 5Trending

Top 10 Coaches in CFB

J.D. PicKell ranks college football coaches

Get the On3 Top 10 to your inbox every morning

By clicking "Subscribe to Newsletter", I agree to On3's Privacy Notice, Terms, and use of my personal information described therein.

Add to that the unexpected success at No. 4 TCU, No. 5 Tennessee and No. 7 LSU, and there’s more than just pent-up energy. These are not spoiled fans.

That atmosphere makes for great TV. The Tide and Tigers attracted 7.58 million viewers Saturday, ESPN’s biggest regular-season audience since 2016, according to Sports Media Watch. The website also pointed out that earlier in the day, Tennessee and Georgia on CBS drew 13.06 million viewers, more than the Houston Astros’ Game Six win over Philadelphia Phillies to clinch the World Series.

If you’re a visiting coach, the only solution seems to be for your team to shut up the hostile fans by playing well. The officials want nothing to do with taming the home crowd. They’ve tried. Shaw recalled that the NCAA had a crowd noise rule some thirty years ago in his early days of officiating.

“The quarterback, typically under center, would raise both hands and look back at the referee, and the referee made a decision,” Shaw said. “If we felt the interior linemen couldn’t hear, we’d stop and make an announcement.”

The NCAA abandoned that rule.

“The minute you stop the game,” Shaw said, “if you think it was bad, it’s getting ready to get louder.”

“Pent-up” energy suggests that it will be expended at one point. Maybe the post-COVID excitement will die down. The audio operator on Mobley’s telecasts, Devin Barnhart, said the sound this season isn’t louder than pre-COVID levels, just louder than the past two seasons. He believes that may explain the discomfort of the players. “The kids never played in this,” he said.

Maybe the players will get accustomed to the noise. Human nature suggests that someday we will again take attending games for granted. In the meantime, college football crowds are splitting ears. Their teams have the winning record at home to show for it.