50 years after epic Nebraska-Oklahoma game, we catch up with the hero

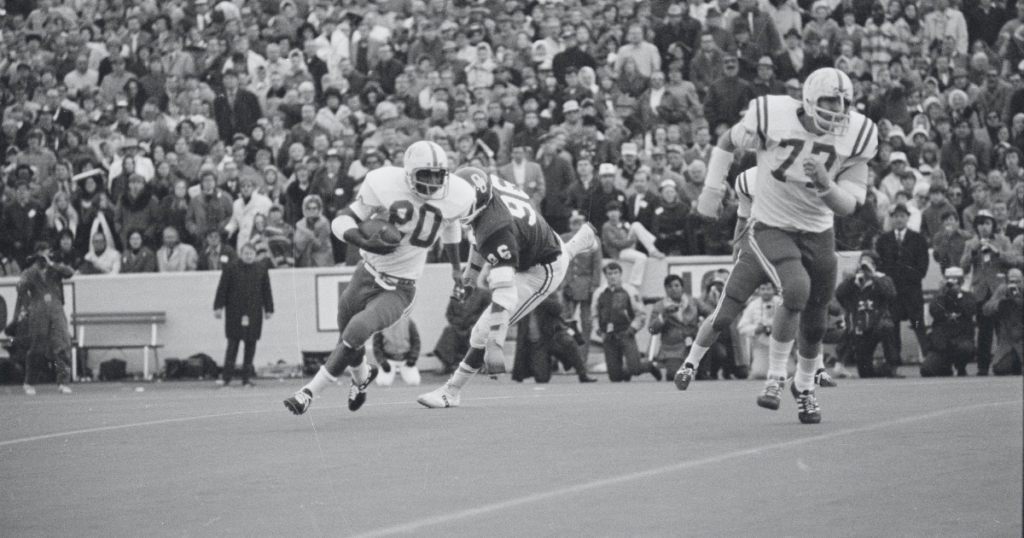

The CliffsNotes of college football history teach us to associate the 1971 game between No. 1 Nebraska and No. 2 Oklahoma with Husker Johnny Rodgers’ punt return, the whirling, feinting, riveting 72-yard sprint to the end zone in the Huskers’ 35-31 victory.

History buffs know that Rodgers returned that punt for a touchdown in the first quarter of a game decided in the final two minutes. But the legend, the one that pins the victory on Rodgers, is too intoxicating.

“As great as Johnny’s return was, a lot of things happened after that that had to happen,” Jeff Kinney said. “But I’m glad he did it. Otherwise, we wouldn’t have won.”

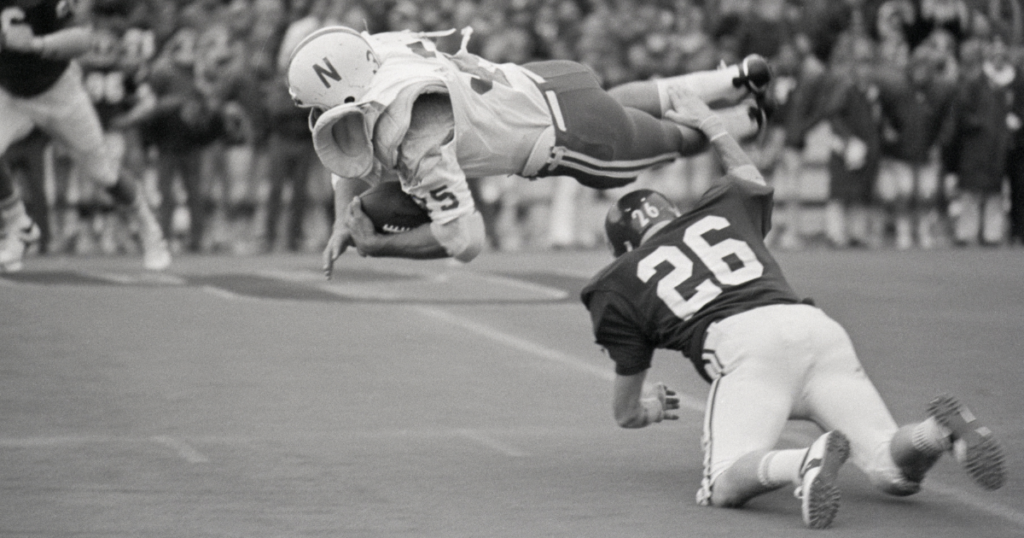

Kinney started at I-back, the bell cow position in Nebraska coach Bob Devaney’s I-formation. Kinney was a senior starter on that cold, crisp Thanksgiving Day in Norman, Okla. He ran the ball 31 times. He rushed for 174 yards. And he scored four touchdowns, the rest of the Huskers’ touchdowns, including the game-winner from the Sooners’ 2 with 1:38 to play.

I haven’t checked with the Nebraska State Board of Education, but I’m reasonably sure Kinney’s heroics are taught in state history classes from Mitchell to Omaha. It’s the other 49 states where Kinney has remained anonymous. Just think how that kind of performance would be treated in today’s overheated, hyper-tweeted media atmosphere.

Nebraska returns to Gaylord Family Memorial Stadium on Saturday to celebrate the golden anniversary of one of the great college football games of the TV era. The Huskers are an also-ran in the Big Ten. The Sooners remain a national power. That shouldn’t diminish the legacy of the game a half-century ago, the one that decided the Big Eight Conference championship.

“In the land of the pickup truck and cream gravy for breakfast, down where the wind can blow through the walls of a diner and into the grieving lyrics of a country song on a jukebox — down there in Big Eight territory — they played a football game on Thanksgiving Day . . . ” began the Sports Illustrated story by Dan Jenkins, the poet laureate of college football.

When he got through waxing rhapsodic, Jenkins also wrote this: “(I)t is impossible to stir the pages of history and find one (game) in which both teams performed so reputably for so long throughout the day.”

The story holds up. The game holds up. ESPN, in its College Football 150 celebration in 2019, named it the greatest game ever. The network named the ’71 Huskers the greatest team ever.

And yet even Jenkins mentioned Kinney more as a supporting actor than as a star. Maybe it was the nature of Kinney’s play. He scored from 1, 3, 1 and 2 yards out. Sportswriters don’t swoon over line plunges. Jenkins called Kinney a “refrigerator truck” of a back. Jim Walden, a Huskers defensive assistant 50 years ago who went on to coach at Washington State and Iowa State, said Kinney played ahead of his time.

“Didn’t have tremendous speed, which probably hurt his pro situation, but doggone it, he could catch the ball,” Walden, 83, said from his Idaho home. “He was such a threat. We didn’t throw to him a lot because we didn’t throw the ball anywhere near what they do today. In that era, it was wishbone and I-formation. Neither one of those offenses is geared to space and throwing balls.”

Nebraska trailed 17-14 at halftime, having gained only 91 yards of total offense. The Huskers recommitted to the running game after halftime. Cue Kinney. On the first play of the second half, he broke a tackle and ran for 22 yards.

“We did make some adjustments on the blocking side of it,” Kinney said. “Just more a matter of moving the attack point a little further out, moving it to the tackle vs. the guard. They allowed me to make the read on however the guy was blocking.”

Walden said the real halftime adjustment came in deciding to feed Kinney the ball.

“Part of it had to do with the respect they had for the defensive front and the defensive team at Oklahoma,” Walden said of the Huskers’ offensive coaches. “That’s the best football team never to be No. 1 in United States history, in my opinion. I think that’s what it was. I think they just said, we respect them. But, hey, we got to go back to doing what we do. If they’re better than we are, they’ll stop it. But let’s at least make them stop it.”

Top 10

- 1New

Shilo Sanders

Lands with NFL team

- 2

Picks by Conference

The final tally in NFL Draft

- 3Trending

Mel Kiper

Eviscerates NFL: 'Clueless'

- 4

D.J. Uiagalelei

Signs NFL free agent deal

- 5Hot

Quinn Ewers drafted

Texas QB off the board

Get the On3 Top 10 to your inbox every morning

By clicking "Subscribe to Newsletter", I agree to On3's Privacy Notice, Terms, and use of my personal information described therein.

The Huskers scored twice in the third quarter to take a 28-17 lead. The Sooners responded with two touchdowns to retake the lead with 7:10 remaining. And that’s when Kinney took over. On Nebraska’s 74-yard scoring drive, Kinney reeled off runs of 17 and 13 yards. When the Huskers reached the Sooners’ 15, Kinney carried the ball on the next four snaps, barreling in over the left side for the 2-yard touchdown that will live in Nebraska for as long as they sing “Hail Varsity.”

Kinney continued to an NFL career in Kansas City and Buffalo. He retired, returned to Kansas City and made a life outside of the heroic persona he has maintained in his native Nebraska. There, the wattage of his stardom has remained intact. He is one of theirs, a native of McCook, a town of nearly 8,300 then and nearly 7,500 now. Kinney has a hearty laugh and an easy way about him. Like most Nebraskans, he could keep his ego in a thimble.

“I got to tell you the truth,” Kinney said. “The game just got bigger and bigger as time went on. I have no idea why it did. Most of the people who were adults at that time probably aren’t alive.”

Yet he still gets three or four cards a month in the mail, asking for an autograph. Fifty years later, he still is asked to speak publicly.

“It’s kind of rewarding to have somebody come up and say, ‘You know, I used to ride in the tractor with my dad and we would have the football game on every Saturday, and you were his favorite Nebraska player,’ ” Kinney said. “It’s just how it’s been passed on from grandpa to son or daughter. It’s just the way Nebraska football is.”

Other items were passed from son to father. After the game, Kinney said, he began to walk off the field, his white tearaway jersey in tatters. “Right in the middle of the field, my dad showed up,” Kinney said. “He was able to get the rest of my jersey off. He took it home and gave it to the local barber shop there in McCook, Nebraska.”

Cecil Kinney brought it to Harry’s Barber Shop on West Seventh Street in McCook, where the jersey hung until Harry Lebsack retired in 2008. Last Kinney heard, the jersey is at McCook High School.

There’s one other thing that Kinney remembers from the post-game celebration. The Huskers’ plane landed at the Lincoln airport and, in those more innocent times, couldn’t taxi to the terminal.

“There were like thirty-something thousand people at the airport,” Kinney said. “So they just let us out. We got to walk through the crowd. Signed autographs. Everybody was cheering. Band was playing. It was just a continuation.”

In some ways, the celebration has never stopped. Maybe Kinney played the way Nebraska likes to think of itself — workmanlike, unassuming. They revere Johnny Rodgers the way the rest of college football does. But they make room on the pedestal for a refrigerator truck.