Self-created video content can be an NIL boon for athletes

Before July 1, Jon Seaton was an obscure 285-pound offensive lineman at FCS Elon University. But since the birth of the Name, Image and Likeness era, Seaton has become a sought-after social media influencer whose 1.5 million TikTok followers make him highly marketable.

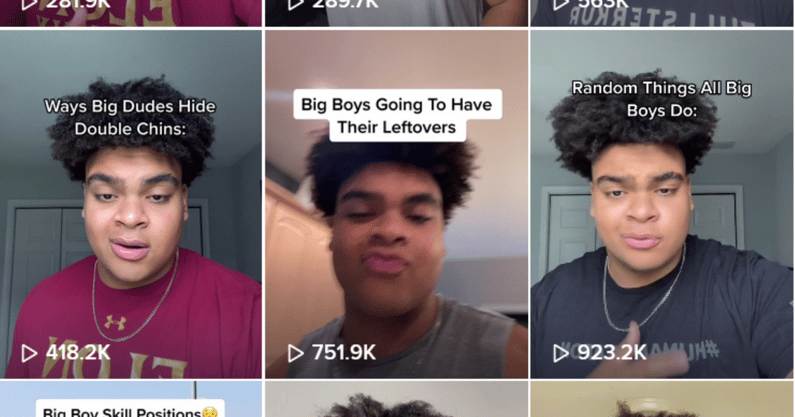

Seaton’s posts are long on self-deprecating humor — “Things that big boys do to look less big” and “Back to school tips for big guys” among them — that routinely garner hundreds of thousands and as many as 6.3 million page views. Although the second-year college student has yet to appear in a game this season, Seaton has a Los Angeles-based agent, Pat Curran.

In the media space, content is king. And while high-profile deals have focused on Alabama quarterback Bryce Young securing his own podcast; Oklahoma running back Kennedy Brooks becoming the first college athlete to start a paid subscriber text messaging community; or Texas A&M players monetizing interviews with the popular TexAgs site, there is immense NIL potential for athletes with the prowess, personality or eagerness to create their own video content with little more than their own phone. The more of those three boxes they check, the greater the potential.

Jim Cavale is the CEO and founder of INFLCR, which provides 170 NCAA Division I athletic departments brand-building technology to assist their athletes in maximizing their NIL value. He told On3 that while it’s easier for an elite athlete to monetize content on social media, the prime ingredient remains initiative. Lacking that makes them “just a good athlete who doesn’t use social media,” he said. On the other hand, there could be lower-profile athletes “who are really good at creating value through this relationship with the fan that creates a story and a transparency or vulnerability in that relationship.”

Video content appeals to Gen Z

In the nascent NIL age, self-creating video content on social media channels is one of the areas where potential has yet to be fully tapped. It’s a format — especially with shorter, lighter, often humorous TikTok videos — uniquely suited for the Gen Z demographic that includes both the athletes as well as most of their followers. Gen Zers tend to reject over-produced videos, possess a strong BS meter and seek original content tailored to their individual preferences.

Chris Marinak, Major League Baseball’s chief operations and strategy officer who leads the league’s efforts in growing a younger audience through technology, a few months ago told me that one of the defining characteristics of the Gen Zers is “they want to get their hands dirty and build things on their own. They want to build their own experiences themselves because they think that is more authentic and original. The other thing is all generations want to be part of communities, but Gen Z is comfortable with and seeks a digital community.”

Young fans of college athletes want to see and hear athletes be themselves. Industry sources say authentic content exhibiting an athlete’s personality—with a brand’s ad spot embedded into it — is more popular than merely video consisting entirely of an athlete shilling for a brand. In fact, a recent marketing survey found that more than 20 percent of respondents said that they would unfollow a brand on Facebook and Twitter if they believed the content was boring or repetitive. And more than 15 percent said they would unfollow a brand on Facebook, LinkedIn and Twitter if it posted more than six times per day.

Tiffany Kelly, the founder of the start-up Curastory, is one entrepreneur striving to unlock monetization potential for college athletes through self-created video content. Founded in 2019, Curastory, which this week announced a $2.1 million seed round of funding, works with some 300 athletes, including the NBA’s Victor Oladipo, the NFL’s Tyreke Hill and nearly 150 brands. While the company works with fewer than 100 current college athletes, Kelly envisions continued growth as athletes see the content creation process is seamless.

“The majority (of athletes) are Gen Z and they understand content and understand social media like in a heartbeat,” Kelly, who has worked for ESPN and the Miami Heat, told On3. “What they need assistance with is just all the rules and red tape and things that go with it. A lot didn’t know that they lose ‘X’ amount of followers every time they post a sponsored post that isn’t original content. As universities continue to educate athletes on that, I think it will grow and we’ll see a lot more content out there.”

Top 10

- 1New

Brad Brownell

Clemson HC talks IU rumors

- 2

Joe Lunardi

Shreds the ACC

- 3Hot

Chad Baker-Mazara

Bruce Pearl fires back

- 4Trending

Nick Saban

Receives FCC criticism

- 5

New Bracketology

Wednesday update

Get the On3 Top 10 to your inbox every morning

By clicking "Subscribe to Newsletter", I agree to On3's Privacy Notice, Terms, and use of my personal information described therein.

With Curastory, athletes can earn $30 per 1,000 page views on a brand’s ad spot that is embedded as a brief interruption within the athlete’s self-created video. The company matches brands with athlete content most appropriate for what the brand seeks. Brands then request the placement of their ad spot within an athlete’s particular video. There is a wide spectrum of what videos can encompass, of course, including everything from day-in-the-life videos to a look at what athletes eat in a day.

Investing time to build a brand

Less than three months into the NIL era, Cavale estimated that less than 10 percent of all college athletes are truly willing to invest time to build their brands on social media. And among those who are willing, even fewer are high-profile athletes. The exception, Cavale said, is an athlete like Oregon women’s basketball player Sedona Prince, who has 246,000 followers on Instagram and more than 43,000 on Twitter. Cavale said he has never been around a high-profile athlete who takes as much initiative on social media.

“The better the athlete you are, the more people care and want to get to know you, and they want to do that while you’re still playing,” Cavale said. “There’s a life expectancy here that athletes need to be mindful of because people won’t care or want to engage with them later in life as much as they do right now. And you’ve got to take advantage of that.”

Eric Winston, the former University of Miami and 12-year NFL lineman, is the chief partnerships officer for OneTeam Partners, whose many priorities include focusing on NIL group-licensing deals. From self-creating videos to lucrative podcast deals, Winston said to expect “all sorts of media plays” by athletes, with many initiatives offering the potential to build off them after college if they capture and retain an audience.

Now that the industry has moved beyond the initial flurry of NIL deals, Kelly believes athletes’ hesitancy in creating video content will diminish now that there is an increasing understanding of NIL rules and monetary potential.

“People are interested in people, and people follow people” on social media, Kelly said. “This is why I think the creator economy is taking off the way that it is. People are consuming content in much more fragmented ways, and it’s going to be individual creators. It’s only going to continue to grow. You wouldn’t want to buy a magazine that was all ads. You actually want to buy a magazine that has original content in it.”